Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Wisconsin’s free newsletter here.

For nearly two weeks following Election Day in 2024, former U.S. Senate candidate Eric Hovde, a Republican, refused to concede, blasting “last-minute absentee ballots that were dropped in Milwaukee at 4 a.m., flipping the outcome.”

But, just as when Donald Trump blamed Milwaukee for his 2020 loss, Hovde’s accusations and insinuations about the city’s election practices coincided with a surge of conspiratorial posts about the city. Popular social media users speculated about “sabotage” and “fraudulently high” turnout.

Hovde earlier this year told Votebeat that he believes there are issues at Milwaukee’s facility for counting absentee ballots, but he added that he doesn’t blame his loss on that. He didn’t respond to a request for comment in December for this article.

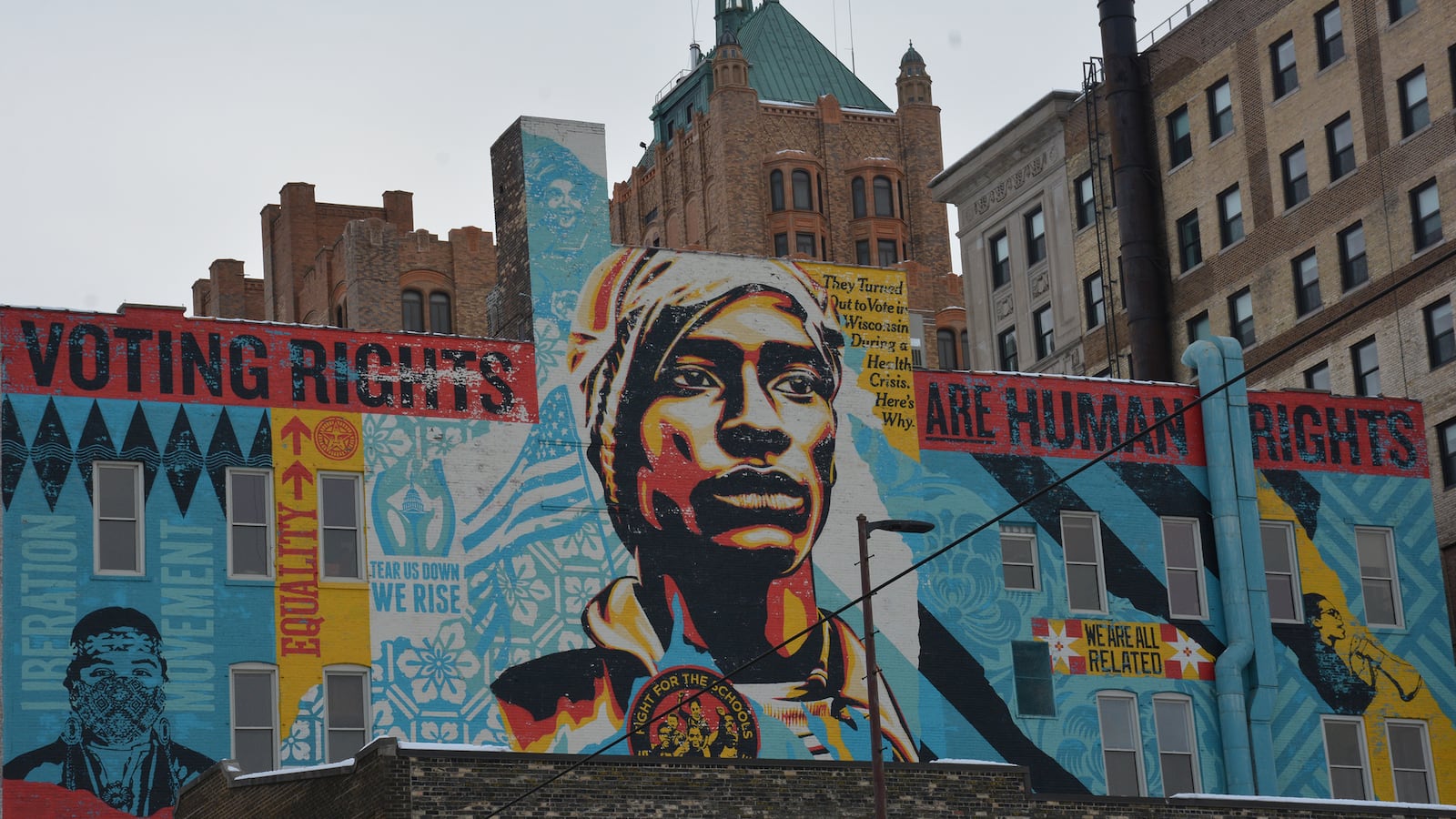

In Wisconsin’s polarized political landscape, Milwaukee has become a flashpoint for election suspicion, much like Philadelphia and Detroit — diverse, Democratic urban centers that draw outsized criticism. The scrutiny reflects the state’s deep rural-urban divide and a handful of election errors in Milwaukee that conspiracy theorists have seized on, leaving the city’s voters and officials under constant political pressure.

That treatment, Milwaukee historian John Gurda says, reflects “the general pattern where you have big cities governed by Democrats” automatically perceived by the right “as centers of depravity [and] insane, radical leftists.”

Charlie Sykes — a longtime conservative commentator no longer aligned with much of the GOP — said there’s “nothing tremendously mysterious” about Republicans singling out Milwaukee: As long as election conspiracy theories dominate the right, the heavily Democratic city will remain a target.

Milwaukee voters and election officials under constant watch

Milwaukee’s emergence as a target in voter fraud narratives accelerated in 2010, when dozens of billboards in the city’s predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods showed three people, including two Black people, behind bars with the warning: “VOTER FRAUD is a FELONY — 3 YRS & $10,000 FINE.”

Community groups condemned them as racist and misleading, especially for people who had regained their voting rights after felony convictions. Similar billboards returned in 2012, swapping the jail bars for a gavel. All of the advertisements were funded by the Einhorn Family Foundation, associated with GOP donor Stephen Einhorn, who didn’t respond to Votebeat’s email requesting comment.

Criticism of Milwaukee extends well beyond its elections. As Wisconsin’s largest city, it is often cast as an outlier in a largely rural state, making it easier for some to believe the worst about its institutions — including its elections.

“One of the undercurrents of Wisconsin political history is … rural parts versus urban parts,” said University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee political scientist and former Democratic legislator Mordecai Lee. As the state’s biggest city by far, “it becomes the punching bag for outstate legislators” on almost any issue.

“People stay at home and watch the evening news and they think if you come to Milwaukee, you’re going to get shot … or you’re going to get run over by a reckless driver,” said Claire Woodall, who ran the city’s elections from 2020 to 2024.

Election officials acknowledge Milwaukee has made avoidable mistakes in high-stakes elections but describe them as quickly remedied and the kinds of errors any large city can experience when processing tens of thousands of ballots. What sets Milwaukee apart is the scrutiny: Whether it was a briefly forgotten USB stick in 2020 or tabulator doors left open in 2024, each lapse is treated as something more ominous.

Other Wisconsin municipalities have made more consequential errors without attracting comparable attention: In 2011, Waukesha County failed to report votes from Brookfield when tallying a statewide court race — a major oversight that put the wrong candidate in the lead in early unofficial results. In 2024, Summit, a town in Douglas County, disqualified all votes in an Assembly race after officials discovered ballots were printed with the wrong contest listed.

“I don’t believe that there is anywhere in the state that is under a microscope the way the City of Milwaukee is,” said Neil Albrecht, a former executive director of the Milwaukee Election Commission.

Black Milwaukeeans say racism behind scrutiny on elections

Milwaukee grew quickly in the 19th century, built by waves of European immigrants who powered its factories and breweries and helped turn it into one of the Midwest’s major industrial cities. A small Black community, searching for employment and fleeing the Jim Crow South, took root early and grew substantially in the mid-20th century.

As industry declined, white residents fled for the suburbs, many of which had racist housing policies that excluded Blacks. That left behind a city marked by segregated schools, shrinking job prospects, and sharp economic divides. The split was so stark that the Menomonee River Valley became a shorthand boundary: Black residents to the north, white residents to the south — a divide Milwaukee never fully overcame.

The result is one of the most segregated cities in the country, a place that looks and feels profoundly different from the overwhelmingly white, rural communities that surround it. That contrast has long made Milwaukee an easy target in statewide politics, and it continues to feed some people’s suspicions that something about the city — including its elections — is fundamentally untrustworthy.

The Rev. Greg Lewis, executive director of Wisconsin’s Souls to the Polls, said the reputation is rooted in racism and belied by reality. He said he has a hard enough time getting minorities to vote at all, “let alone vote twice.”

Albrecht agreed.

“If a Souls to the Polls bus would pull up to [a polling site], a bus full of Black people, some Republican observer would mutter, ‘Oh, these are the people being brought up from Chicago,’” he said. “As if we don’t have African Americans in Milwaukee.”

After former Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes — a Black Milwaukeean and a Democrat — lost his 2022 U.S. Senate bid to unseat U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson, Bob Spindell, a Republican member of the Wisconsin Elections Commission, emailed constituents saying Republicans “can be especially proud” of Milwaukee casting 37,000 fewer votes than in 2018, “with the major reduction happening in the overwhelming Black and Hispanic areas.”

The message sparked backlash, though Spindell rejected accusations of racism. Asked about it this year, Spindell told Votebeat he meant to praise GOP outreach to Black voters.

Milwaukee organizer Angela Lang said she finds the shifting narratives about Black turnout revealing. “Are we voting [illegally]?” she said. “Or are you all happy that we’re not voting?”

History of real and perceived errors increases pressure on city

The scrutiny directed at Milwaukee falls on voters and the city employees who run its elections.

Milwaukee’s most serious stumble came in 2004, when a last-minute overhaul of the election office contributed to unprocessed voter registrations, delayed absentee counts, and discrepancies in the final tally. Multiple investigations found widespread administrative problems but no fraud.

“It was hard coming in at that low point,” said Albrecht, who joined the commission the following year, saying it gave Milwaukee the reputation as an “election fraud capital.”

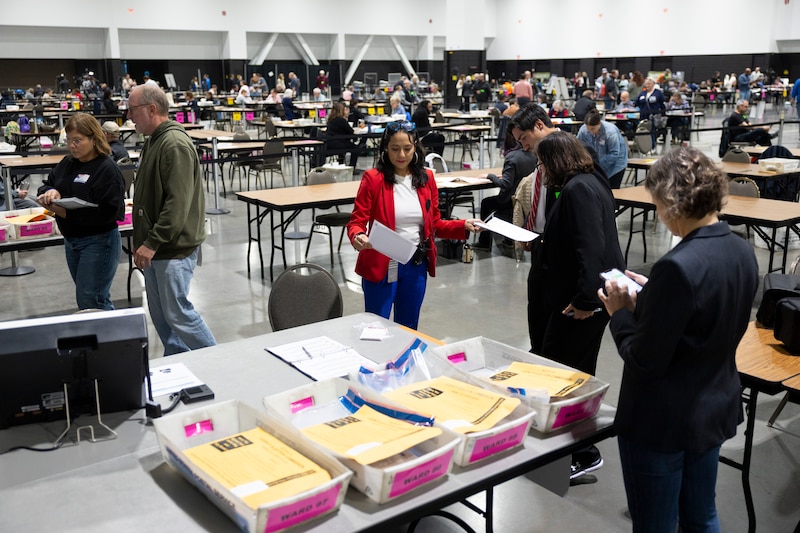

In 2008, the city created a centralized absentee ballot count facility to reduce errors at polling places and improve consistency. The change worked as intended, but it also meant Milwaukee’s absentee results — representing tens of thousands of votes — were often reported after midnight, sometimes shifting statewide margins.

That timing is largely a product of state law: Wisconsin is one of the few states that prohibit clerks from processing absentee ballots before Election Day. For years, Milwaukee officials have asked lawmakers to change the rule. Instead, opponents argue the city can’t be trusted with extra processing time — even as they criticize the late-night results all but unavoidable under the current rule.

That dynamic was on full display in 2018, when former Gov. Scott Walker, trailing in his reelection bid, said he was blindsided by Milwaukee’s 47,000 late-arriving absentee ballots and accused the city of incompetence.

Proposals to allow administrators more time to process ballots — and therefore report results sooner— have repeatedly stalled in the Legislature. The most recent passed the Assembly last session but never received a Senate vote, with some Republicans openly questioning why they should give Milwaukee more time when they don’t trust the city to handle the ballots with the time it already has.

“The late-arriving results of absentee ballots processed in the City of Milwaukee benefits all attempts to discredit the city,” Albrecht said.

Without the change, to keep up with other Wisconsin municipalities, Milwaukee must process tens of thousands of absentee ballots in a single day, a herculean task. “The effect of not passing it means this issue can be kept alive,” said Lee, the UW–Milwaukee political scientist.

Some Republicans acknowledge that dynamic outright. Rep. Scott Krug, a GOP lawmaker praised for his pragmatic approach to election policy, has long supported a policy fix. This session, it doesn’t appear to be going anywhere.

Krug said a small but influential faction on the right has built a kind of social network around election conspiracy theories, many focused on Milwaukee. Because the tight counting window is part of the fuel that keeps that group going, he said, “a fix is a problem for them.”

2020 marked the shift to ‘complete insanity’

Albrecht said that while Milwaukee had long operated under an unusual level of suspicion, the scrutiny that followed 2020 represented a shift he described as “complete insanity.”

That year, in the early hours after Election Day, Milwaukee released its absentee totals, but then-election chief Woodall realized she’d left a USB drive in one tabulator. Woodall called her deputy clerk about it, and the deputy had a police officer take the USB drive to the county building. The mistake didn’t affect results — the audit trail matched — but it was enough to ignite right-wing talk radio and fuel yet more conspiratorial claims about the city’s late-night reporting.

The scrutiny only intensified. A joking email exchange between Woodall and an elections consultant, taken out of context, was perceived by some as proof of fraud after Gateway Pundit and a now-defunct conservative state politics site published it. Threats followed, serious enough that police and the FBI stepped in. Woodall pushed for increased security at the city’s election office, saying that “there was no question” staff safety was at risk.

A similar dynamic played out again in 2024, when workers discovered that doors on absentee tabulators hadn’t been fully closed. With no evidence of tampering but anticipating backlash, officials zeroed out the machines and recounted every ballot. The fix didn’t stop Republicans, including Johnson, from suggesting something “very suspicious” could be happening behind the scenes. Johnson did not respond to a request for comment.

Meanwhile, errors in other Wisconsin communities, sometimes far more consequential, rarely draw similar attention. Take Waukesha County’s error in 2011 — a mistake that swung thousands of votes and affected which candidate was in the lead. “But it didn’t stick,” said UW–Madison’s Barry Burden, a political science professor. “People don’t talk about Waukesha as a place with rigged or problematic elections.”

In recent years there was only one substantiated allegation of serious election official wrongdoing: In November 2022, Milwaukee deputy clerk Kimberly Zapata was charged with misconduct in office and fraud for obtaining fake absentee ballots.

A month prior, she had ordered three military absentee ballots using fake names and sent the ballots to a Republican lawmaker, an effort she reportedly described as an attempt to expose flaws in the election system. Zapata said those events stemmed from a “complete emotional breakdown.” She was sentenced to one year of probation for election fraud.

“We didn’t hear as much from the right” about those charges, Woodall said.

More recently, the GOP has raised concerns about privacy screens — a curtain hung last November to block a staging area and, earlier this year, a room with frosted windows. Republicans seized on each, claiming the city was hiding something.

Paulina Gutiérrez, the city’s election director, told Votebeat the ballots temporarily kept behind the curtain “aren’t manipulated. They’re scanned and sent directly onto the floor,” where observers are free to watch the envelopes be opened and the ballots be counted.

But the accusations took off anyway. Even Johnson, the U.S. senator, suggested the city was “making sure NO ONE trusts their election counts.”

Alexander Shur is a reporter for Votebeat based in Wisconsin. Contact Alexander at ashur@votebeat.org.