A version of this post was originally distributed in as a special Election Day newsletter. Sign up for Votebeat’s weekly newsletter here.

Last night was a squeaker, but Glenn Youngkin will be Virginia’s next governor. Even squeakier was New Jersey’s gubernatorial election, which remains too close to call. Many counties are still counting ballots, and the state’s newish vote-by-mail option has significantly slowed counting, as was expected. As of last night’s partial results, incumbent Gov. Phil Murphy was only up about 1,100 votes over GOP challenger Jack Ciattarelli, though his margin widened to several thousand as of earlier today. The closest-ever election in New Jersey, the 1981 gubernatorial race, was won by a margin of about 1,800 votes.

Last night’s results reporting in New Jersey, which at one point showed Ciattarelli slightly leading, was mired in confusion. Across the state’s 21 counties, each had approached counting more than 700,000 mail-in and early votes slightly differently, making it unclear if these were included in the totals. Mail-in ballots postmarked by Election Day can be counted as long as they arrive by Nov. 8, meaning the counting will drag on for several more days. The high Republican turnout and Democratic malaise in New Jersey took the country by surprise — Murphy had been expected to run away with it.

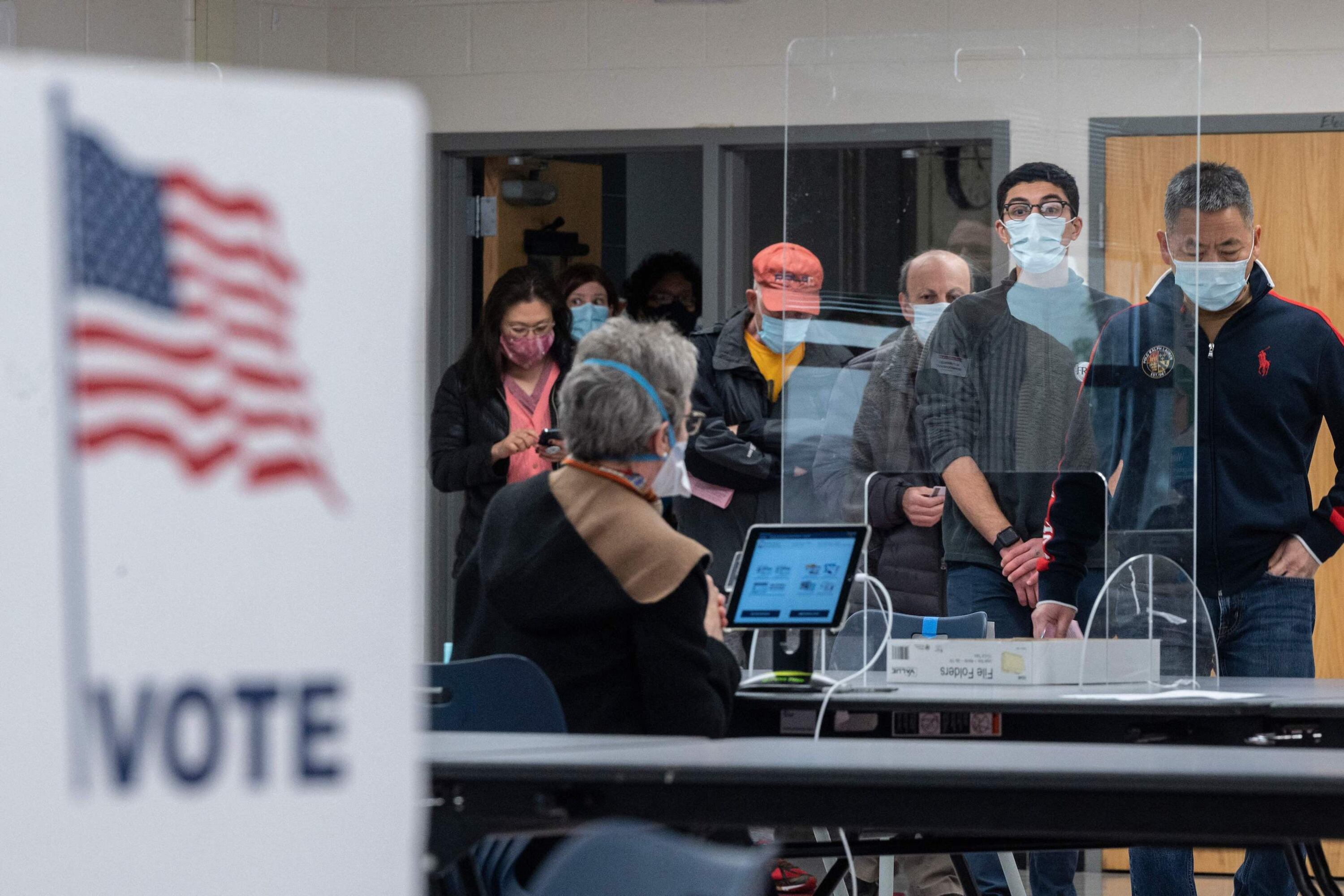

But despite the shocking results, both states mostly had a surprisingly smooth election experience, as did the rest of the nation. The setbacks reported so far were minor and explainable. New Jersey had made several recent changes to elections, including expanding vote by mail and introducing e-pollbooks. While there were some growing pains across the state with the e-pollbooks in the morning — including reports about connectivity problems with a new highly secure wifi router — these issues were resolved after the first few hours. The delays prompted the ACLU and League of Women Voters New Jersey to rush to court, seeking to keep polls open an extra 90 minutes, but the judge — echoing the state attorney general and both gubernatorial campaigns — ruled that such an extension wasn’t necessary.

Virginia saw voter confusion over the state’s witness signature requirement, which had been waived during the coronavirus public health emergency but was back in force during this election. That led several counties to report last month that hundreds of ballots were arriving without the witness signatures and would be rejected if voters didn’t resubmit ballots correctly. It’s too early to know how many voters’ ballots will ultimately be rejected for that reason — not enough to change the election outcomes but perhaps enough to show that the requirement harms voting access. And while there was speculation that the political environment in Virginia would explode into problems with poll watchers, intimidation, or other partisan hijinks, the night appears to have been absent of these.

Much has been written about whether Virginia is a political bellwether for the rest of the country’s attitude on Trump and for the parties’ prospects in 2022, but to be honest, I could care less. A far more important consideration, and frankly I think more accurate, is this election’s significance in foreshadowing how the American public reacts to imperfect and close elections post-2020. Were there massive errors at the polls? Nope. Was there a scourge of misinformation around counting processes? Not any that appear to have gotten any traction. Did the public react apoplectically to expected and routine problems with machines or delays in the count? They have not. Did the candidates appropriately concede? They have so far.

Also notable is that New Jersey and Virginia have expanded voting options recently, and last night was a sign that increased access doesn’t harm Republicans’ vote share. As Texas Tribune Editor in Chief Sewell Chan notes, “Might this cause R’s elsewhere to rethink strategy of making it harder to vote?”

The curtains haven’t completely closed on this election, so anything is possible. Off-year elections simply don’t produce the kind of system-testing turnout that even midterm elections will produce next year (though a few counties in Virginia did have whopping turnout). But even with those caveats in mind, I’m excited and feel optimistic about how much the public has learned about election administration in the last year. Some of the problems we saw in Virginia and New Jersey — while minor and completely expected — would have thrown the voting public for a loop in 2020. Perhaps voters are seeing through the misinformation and realizing that no election goes perfectly. Or perhaps this shows how differently voters understand elections in these two states compared with places like Pennsylvania or Arizona. The true test will be next year’s midterm elections.

Other Election Day News

- It looks like the biggest voting snafu yesterday happened in Stockbridge, Georgia, where dozens of voters were turned away after the voting machines weren’t working at three polling sites. Mayor Pro Tem Elton Alexander called it a “collapse.” Voting machine problems aren’t atypical, of course, but what appears to be was the absolute lack of paper ballot backups at these voting locations. Instead, poll workers directed voters to a separate voting location — the only other functional polling place in town. There were no major errors in the rest of Georgia.

- The city of Ann Arbor, Michigan, has voted — with 73 percent in favor! — to adopt ranked choice voting for municipal elections. The change would not go into effect unless the legislature authorizes the use of such a voting style. Ann Arbor experimented with the model in the ’70s, but it didn’t last long. Looks like it’s back in style.

- New York City Republican mayoral candidate Curtis Sliwa attempted to vote with his cat, named Gizmo, yesterday. Predictably, it ended badly. The cat was not allowed into the polling location and Sliwa screamed at the poll workers for several minutes, daring them to arrest him, prior to relenting. Sliwa, who has made rescue animals (specifically cats) among his biggest policy platforms, called the poll workers “hostile.” “Gizmo was on the kill list,” Sliwa told local reporters. “Thank God my wife was able to save Gizmo.” Eric Adams, the Democratic candidate and winner, brought a picture of his late mother to the polls. This was allowed.

- Otherwise things appear to have gone basically fine in New York, aside from some poll worker shortages causing delays in Brighton Beach.

- And in Maine, a race for Portland City Council has ended in a tie, which will be resolved by drawing lots. The method, which is procedure, entails “making a decision or selection by choosing something, often slips of paper, at random.” The person who wins the drawing wins the seat. Confusingly, the procedure is exactly the opposite under state law, where the name drawn would lose.

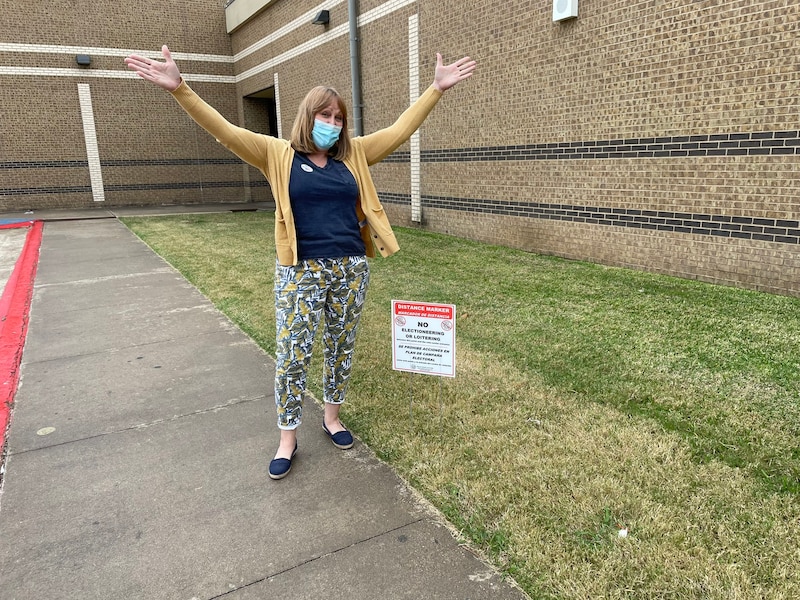

Poll Worker Spotlight: My Mom!

And lastly, a moment of family pride for this Election Day edition: My mom, Lori Huseman, was an election judge in Garland, Texas yesterday — her first experience as a poll worker. And, readers, she loved it. “Oh, I’m doing this again,” she said to me over a turkey sandwich she’d packed for the day. “This is great.”

She was assigned to O’Banion Middle School in Garland — by happenstance, the middle school she attended. “It’s weird that I was doing band practice in here when I was 11 and now I’m working the polls,” she said (she played the drums). “I love it though – how fun is this?” She also married my father at the church immediately next door to the school.

My mom was assisted at her polling location by a college student and a local high school student, who checked voters in as she directed them to their voting machine and answered questions. She only needed to use her election judge chops once — to help her fellow poll worker vote. “She got her driver’s license after she registered, so I had to help her update her voter registration before she could vote,” she said. The process took a few minutes, and the teen was able to cast a ballot normally.

Otherwise it was an uneventful day. No poll watchers showed up, and no voter seemed confused by the process. Just before noon, a state inspector came to ensure all was running normally and gave my mom and her staffers a perfect grade on setup. There wasn’t much on the ballot this time around in Garland, which had no municipal races scheduled, just statewide constitutional amendments. My mom’s polling location only saw 77 voters all day. My mother appears not to be deterred — she intends to recruit her friends. “I’ll be ready for the midterms next year after a day like today,” she said.

My mom, a Republican, said that her experience has made her confident about the voting process. “I didn’t have doubts before, I just knew nothing about how it worked,” she said. Now that she does, she’s even more confident that claims that the 2020 election was flawed are false. “I honestly just don’t see how it could be,” she said. This was really cool for me. I’ve been to lots of polling locations in lots of places, but this is the first time I’ve ever voted at a precinct run by my own mother. And it really drove home for me why I like this stuff so much: People like my mom volunteer to take a day off work, sit in a school gym all day and help other people vote. That’s how democracy works — overnight Americans create thousands of makeshift precincts in fire stations and churches and schools and even restaurants, and we do it all again the next time we have to make a decision. How can you not be romantic about that?