Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Pennsylvania’s free newsletter here.

At the Lancaster County Government Center on Friday, 26 clear-plastic bowls sat in front of blue index cards on a table, each card corresponding to a candidate for Mountville Borough tax collector.

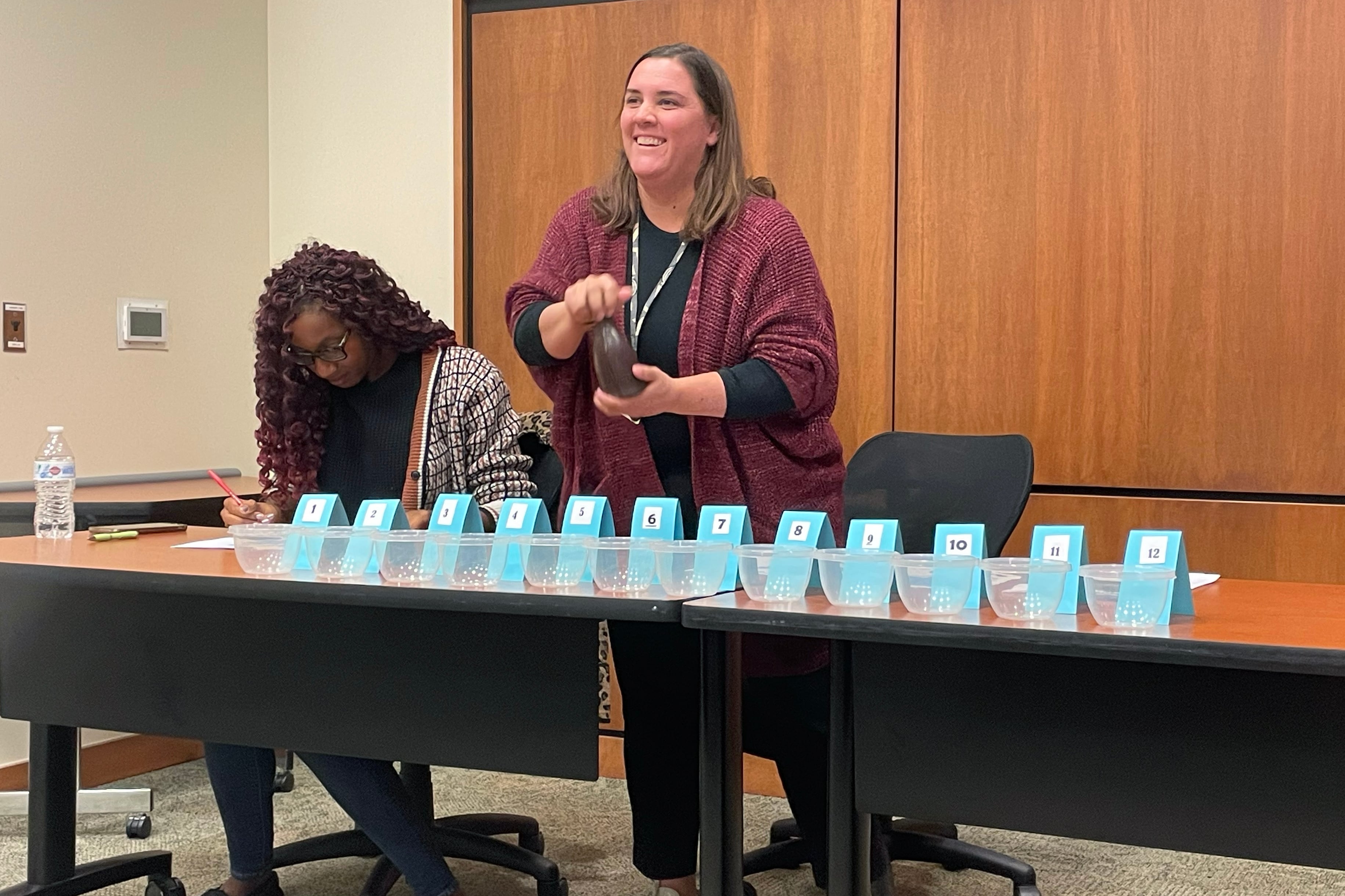

Christa Miller, the county’s election director, shook a leather-wrapped bottle filled with red, numbered marbles, and tipped it upside down until one of the marbles fell into her hand. Down the line of bowls she went, adding a marble to each and calling out the number. When she got to the 19th bowl, with Keith Tarvin’s card behind it, she drew the lowest numbered marble, one.

And so it was decided: Tarvin, who wasn’t there to witness the process, would be the borough’s next tax collector.

The elaborate production was necessary because Tarvin and the other 25 candidates represented by a plastic bowl had all gotten the same number of votes in the Nov. 5 municipal election: a single write-in vote.

Under Pennsylvania law, if an election is tied, the contest goes to a process called the “casting of lots.” This is effectively a game of chance to determine the winner.

Counties use a variety of methods to cast lots, but it typically involves drawing a numbered object — a piece of paper, ping pong ball, playing card, etc. — out of a box or bag. Depending on the county, whichever candidate draws the higher or lower number wins the election.

How often do elections end in a tie?

Tied elections aren’t as rare as one might think. This year alone, Miller said, Lancaster County had about 150 tied races, 95% of which were for inspectors of elections — a type of polling place worker. Lycoming County featured a tie for a Williamsport City Council race and a 13-way tie in a school director election. Westmoreland County, near Pittsburgh, had hundreds of tied poll worker races.

Data from the Public Interest Legal Foundation, a conservative nonprofit legal group based in Virginia, shows there have been at least 468 tied races in Pennsylvania since 2017, though it cautions the data is not comprehensive.

According to PILF data and current and former election officials, ties are most common for positions at the smallest political subdivisions — precincts, boroughs, school districts, etc. Because of the small number of voters in these jurisdictions, and the fact that often no one files to run for low-profile offices such as poll worker, political party committee member, or tax collector, it often just takes one write-in vote to win, leading to frequent ties.

“Most of our ties are multi-way ties, because someone wrote their name down, or their neighbor wrote their name down,” Lycoming County Election Director Forrest Lehman said. “They wrote their own name down as a lark or someone else wrote it down because they thought it was funny.”

That was the case in Lancaster Friday as well. Many candidates were there because they, their spouse, or a friend had written in their name in a blank spot on the ballot.

“I had a guy who emailed me this morning and said, ‘I have told my son to never write me in again,’” Miller said to laughs from the crowd.

In elections for higher office, though, the odds of multiple candidates getting the same number of votes are infinitesimally small. In all of U.S. history, there has never been a tied U.S. Senate race, and no U.S. House races have tied since at least 1898. A spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Department of State said they were unaware of a tie having ever happened in a statewide race in Pennsylvania.

An entertaining way to decide elections

The casting of lots can be a festive affair. Jeff Greenburg, a former election director who now works for the government watchdog group Committee of Seventy, said he used to use red, white, and blue drawing bags and tablecloths to make the event feel more patriotic.

Lehman said Lycoming County puts numbered slips of paper in 1-by-2-inch envelopes, which candidates drew out of a holiday-themed tin, hoping to get the lowest number.

In Lancaster, the candidates who showed up for their drawings seemed to get a kick out of the experience. Miller kept the event lighthearted; winners cheered when the lowest number was drawn for them, and losers cursed with a laugh when they did not.

“This is as exciting as it gets,” Miller joked as she drew marbles for the tax collector race. “Sorry it’s not super exciting.”

Daniel Lyons, a resident of Manheim Township, was there because three friends had written him in for inspector of elections. That was apparently enough to tie him with another candidate, Daryll Benn. Miller drew an 11 for Lyons and a two for Benn, meaning Benn was the winner.

“I had no idea what the casting of lots was,” Lyons said when he received a letter from the county telling him his race was tied and would be decided Friday. But he said the process was “interesting” to watch, and efficient.

Each race took about a minute or less to decide. Only about 20 races had candidates in attendance Friday, which Miller said is typical. Most candidates don’t show up at all.

But even after all the in-person candidates had left, Miller kept shaking her bottle, calling out high and low numbers, determining winners and losers by the flick of the wrist.

Tied elections can be a headache

The casting of lots may seem like just a fun quirk of democracy, but it is also a time- and resource-consuming process for counties. Since a single write-in can win a race, staff have to sort through and record all of the write-in votes. They also have to determine if a candidate is eligible to hold the office, which an out-of-state resident written in by their friend as a joke, or Mickey Mouse, would not be.

Election officials then also have to spend time and money contacting the candidates to let them know about the drawing. (Some decline to participate, as was the case for an additional six candidates in the Mountville tax collector race.) And in the event they win and don’t want the office, staff has to get a written acknowledgment of that from the candidate.

“Many times the winner is someone who has no interest in holding the office at all, so you have wasted a lot of time and effort,” Greenburg said.

Lehman, the Lycoming County elections director, argued the high number of ties in local elections illustrates “why write-in reform is so badly needed in this state.”

As Greenburg explained, if a candidate wants to run a write-in campaign in the primary to get their name on the November ballot, they need to get as many write-in votes as signatures they would be required to get on a nominating petition. So, for example, if a candidate for judge of election needs 10 signatures to get on the primary ballot, a write-in candidate would need to get at least 10 votes, and more than all the others, to win the primary. But that requirement doesn’t exist in the general election, meaning just one write-in vote can be enough to win, or tie, an election.

Creating some threshold for the fall election would help reduce the number of ties, though Greenburg worries that this could make it difficult for anyone to win the smallest, precinct-level races. Another option, Greenburg suggested, would be implementing a policy other states have adopted: requiring write-in candidates to acknowledge ahead of Election Day that they are interested in the office.

“Those are two (reforms) that cost no money but would save counties a lot of time and grief, no doubt,” he said.

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org.