Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Wisconsin’s free newsletter here.

Wisconsin’s controversial practice of randomly removing ballots to resolve discrepancies between the number of ballots and the number of voters would be prohibited under new draft legislation that requires meticulous audits in every county.

The draft proposal, obtained by Votebeat from Republican Rep. Scott Krug, will be formally released this week. Krug said the proposed ban on removing random ballots, known as drawdowns, was inspired largely by a Votebeat investigation highlighting election officials’ reluctance to use the practice and questions about its constitutionality.

“That practice undermines public trust,” Krug said, calling drawdowns “outdated.”

Wisconsin’s law allowing drawdowns is almost as old as the state, and it appears to be used most often in recounts. Other states have had similar laws, but most have repealed them.

Drawdowns occur when records show more ballots cast than the number of voters who cast ballots. These discrepancies usually stem from minor recordkeeping errors or process mistakes.

For example, if poll workers discover an absentee ballot envelope was improperly filled out but had already been separated from its ballot, the ballot still counts, leaving more ballots than valid voters. Because ballots are generally unidentifiable, the law would call for election officials to remove one ballot at random.

Multiple Wisconsin clerks have told Votebeat that they loathe the practice, and national election experts have been flabbergasted that it exists.

A legislative study committee in 2005 questioned the practice’s constitutionality without resolving the issue. Courts have similarly scrutinized its use. The Wisconsin Elections Commission has said a drawdown should be reserved as a last resort “when you cannot explain why you have more ballots than voters.”

Sam Liebert, Wisconsin state director of the group All Voting Is Local and a former clerk, said he once had to conduct a drawdown. He called it “one of the most gut-wrenching things I think I’ve ever done.”

“Every one of those ballots — it’s an American citizen’s hopes and dreams of the candidate or candidates that they want to represent them,” he said.

Although drawdowns are rare and usually limited to recounts, they’ve drawn national attention.

When President Donald Trump tried to overturn the results of the 2020 election in Wisconsin, his team invoked the law to seek a drawdown of 220,000 absentee ballots in Dane and Milwaukee counties, calling the practice “the only legally available remedy” to account for what it alleged were unlawfully cast ballots. The Wisconsin Supreme Court narrowly rejected the effort.

Other states typically require officials to explain discrepancies rather than resolve them by discarding ballots. Krug’s legislation would require exactly that — for election officials to document the discrepancy and record the number and type of excess ballots.

Proposal would require risk-limiting audits

The bill also requires risk-limiting audits, a kind of post-election review designed to give statistical confidence that votes are accurately tallied.

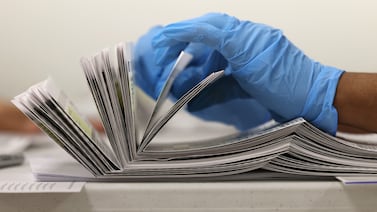

In these audits, workers review a statistically significant sample of ballots that should mirror the vote totals. If the sample doesn’t align with official results within the allowed margin of error, officials review more ballots until it does. The number of selected ballots varies from election to election, depending on how close a race is and how many ballots were cast.

The math behind risk-limiting audits is complex, but election experts and officials have long supported the practice.

Jennifer Morrell, CEO of The Elections Group, a consulting firm, said she has long promoted risk-limiting audits because they can include more ballots than other reviews. They can be laborious in close races but less burdensome in lopsided ones.

Morrell said jurisdictions that have implemented risk-limiting audits have become better at accounting for their ballots and reconciling vote totals, knowing that any issues would become obvious during an audit.

Liebert, from All Voting is Local, called risk-limiting audits “an effective way to ensure a correct count and detect any statistical anomalies,” while boosting voter confidence.

Closer races require larger samples, and in very tight contests, such audits may require a full hand count. Rock County Clerk Lisa Tollefson said that could happen often, as races across the county tend to be quite close.

Krug’s proposal calls for county clerks to perform a risk-limiting audit for the contest garnering the most votes at each general or spring election before they certify the election results. It also calls for an additional audit of a random contest in those elections that the Wisconsin Elections Commission selects.

A pilot program would begin in 2026, with full implementation in 2027.

Alexander Shur is a reporter for Votebeat based in Wisconsin. Contact Alexander at ashur@votebeat.org.