This article was co-published with The Daily Beast.

On Tuesday, the For the People Act, democracy-reform legislation Democrats believe would expand voting access, saw a preview of its fate. The 900-page bill, dealing with everything from election administration to congressional ethics, was the subject of a full day of debate in a Senate committee with nearly 100 proposed amendments.

A total of 10 passed, while the rest went down in flames on largely party-line votes. Its future on the Senate floor looks no better: It will be forced for consideration, debated for hours, and will still fail.

Rather than squabbling over next steps or surrendering, however, the Democrats have a more realistic option that would solve election administrators’ need for funding and would boost the health of elections in a way that is truly for the people.

How? By putting election funding into their infrastructure package.

The need for this alternative strategy is obvious. S1, the Senate’s version of HR1, faces a bleak path: Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) can now force the bill to the floor as part of his power-sharing agreement with Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY). Once there, they will have an easier time amending the bill in ways that failed in committee, because Vice President Kamala Harris can break ties. But, there’s no guarantee Harris will be able to serve that role.

There aren’t 50 Democrats on board with this bill, and Joe Manchin (D-WV)—the most powerful man in the Senate—is, I’m told by staffers, carrying water for a small handful of other Democrats who do not want this bill to pass but are keeping quiet for fear of being punished by leadership. While the Democratic Party is attempting to sell this bill as supported by a unified front, it is very clearly not. And even if it were, they will still need 10 Republicans or filibuster reform, both of which appear unlikely.

Given Manchin’s reservations, expressed in a meeting on Thursday and reported by ABC News, this bill may not make it to the floor at all. (Manchin is far more likely to support a souped-up version of the John Lewis Bill, which does not give meaningful funding to election administrators.)

The For the People Act may be dead on arrival, but election funding does not have to be. While Republicans assail the infrastructure package, niggling with what “infrastructure” really means anyway, no one could feasibly argue that elections are not infrastructure—federal policy designates it, along with power and water, as “critical infrastructure.”

This idea was initially pitched by the Center for Tech and Civic Life, which in 2020 carried out the largest private grant program to election officials in U.S. history.

Unlike the For the People Act, this plan was written in direct coordination with hundreds of bipartisan election officials, who have, for years, been begging for consistent federal funding. Routing funds through the infrastructure plan provides Congress a real ability to equip local officials to give voters the elections they deserve.

“We’ve heard that robust, consistent funding is the most critical need election departments have today, and the lack of adequate, predictable funding is perhaps the greatest barrier election officials face in doing their best work,” they wrote in a statement announcing the initiative.

This is because Congress has funded elections as a secondary thought for years, infusing millions of dollars in reaction to crises: after the hanging chad debacle in 2000, after the cybersecurity failures of 2016, and during the pandemic of 2020. There has never been an effort to consistently fund elections offices such that they can plan ahead for necessary improvements.

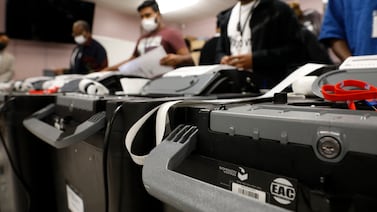

A predictable disbursement of cash to local officials—even with clear parameters for policy priorities—would allow states like Louisiana, which needs machines right now, to buy them. But it would also allow states like Georgia, which just invested millions in new machines, to bank money against the time when they will need to upgrade their machines in eight to 10 years.

Democrats are serious about their desire for automatic voter registration, updating machines, and upgrading physical and digital security. All of these things can be provided for in the infrastructure bill, by offering specific funding for specific plans.

This process will not allow Democrats to be as prescriptive in their policymaking, that’s true, but it will become much easier to get Republicans on board—many of whom already live in and represent states with existing automatic voter registration procedures or more stringent security protocols. The money could be specifically allocated to additional polling locations, or to incentivize states to adopt paper-backed machines and begin to do rigorous auditing—all things with at least some bipartisan consensus.

That elections were left out of the infrastructure package to begin with, for many local election officials, is a head scratcher.

“Elections are clearly infrastructure,” Tiana Epps-Johnson, who heads CTCL, told me. “In order for our elections to improve, they need the funding to plan into the future. This would allow for that.”

In contrast, the For the People Act, as evidenced by the debacle of a committee markup, will not.

Even internally, Democratic staffers on the various committees responsible for the drafting of the bill acknowledged that it began as a messaging bill while they were in the minority. It was introduced in 2019 as a priority, but because Democrats did not yet hold the majority in the Senate, it was meant to send a signal only.

It was introduced again in the House as HR 1 in 2021 to demonstrate their emphasis on voting rights. The bill was then introduced in the newly Democratic-controlled Senate, with almost none of the changes demanded by elections officials, who, as I previously reported, harbored deep reservations about how they could realistically carry out these reforms. Never fear, Democrats said, they would work out the changes in committee.

In the committee markup session, Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) introduced a manager’s amendment addressing the feasibility of the massive election policy changes in the bill. These tweaks to loosen deadlines and add waivers to the mandates were welcomed by election administrators, who saw them as the first step of a good-faith effort to make the bill workable.

“They really did listen to election officials’ concerns,” said one former local official, now active in these negotiations. “I don’t believe they wanted to pass a bill that has unintended consequences, but one that ensures all eligible voters have the same opportunities to successfully participate.”

But Klobuchar’s amendment failed, dashing their hopes again. Both Schumer and McConnell showed up to this markup session, a rare event for Senate leadership, demonstrating how important both parties believe the issue to be. But while Republicans present as a solid bulwark against the bill, Democrats are arguing among themselves as to strategy and the contents of the bill.

If Democrats cannot get a basic amendment addressing basic feasibility concerns passed through a committee they control, it seems their success on the floor isn’t as high as they might claim in public statements. It’s a strategy that’s difficult for local elections officials to digest: Democrats have strapped all of their hopes on voting rights to a single bill that their own party cannot come to a consensus on, and what little funding is made available to elections officials will go down with that ship.

Meanwhile, the John Lewis Voting Rights Act—which Manchin has signaled he supports and may well get a small amount of Republican buy-in—has been left ignored.

Including elections—an obviously critical piece of American infrastructure—in the infrastructure package gives Democrats and interested Republicans a clear opportunity to at least begin to fix the problems that plague our system, even if they cannot fix all of them at once.