A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

Electoral Count Act reform is the new hot topic on the Hill. There’s a real chance for bipartisan progress here, with key moderate Republicans and Democratic leadership both expressing interest in moving forward. And sure, that’s not a material step, but in this deeply divided political environment? It’s the best start we can expect.

Former President Donald Trump is already kicking up a fit. He used the law’s ambiguities to justify his claim in 2021 that the vice president could reject the electoral votes of certain states, and sees the push to rewrite the law as proof that the vice president had such power. “If the Vice President (Mike Pence) had ‘absolutely no right’ to change the Presidential Election results in the Senate, despite fraud and many other irregularities, how come the Democrats and RINO Republicans, like Wacky Susan Collins, are desperately trying to pass legislation that will not allow the Vice President to change the results of the election?” Trump asked.

That’s some simplistic logic, and it ignores the other obvious motivations to reform the text of a 134-year-old law. First among them: Preventing another Jan. 6. I wrote about this a few weeks ago. The rioters and insurrectionists who invaded the seat of American political power last year did so partly because of their misunderstanding of this very law. Many falsely assumed — based on what they were told about the law’s extremely vague and loophole-ridden language — that the vice president could toss out perfectly legitimate votes. They stormed the Capitol, chanting “Hang Mike Pence” for that reason.

The funny thing about Trump’s temper tantrum is that it presents clear motivation for reforming the law. In raging against it, he is proof that the appetite exists to exploit the squishy parameters of the ECA again.

That is not a Democratic-Party-Only concern. The ECA’s broad language about counting Electoral College votes and about who has the power to reject them and for what reasons is a problem for both parties. In theory, either party could make use of the vague standards to reject legitimate votes and swing presidential elections in its favor. As Ed Kilgore of New York Magazine wrote this week, “There’s no particular reason to think it would happen, but the atmosphere of lawlessness surrounding Trump’s attempted election coup might convince Democrats the system is broken so completely that it’s just a matter of which party has the superior strength of will to seize power.”

A bipartisan group of Senators is working on one proposal to reform the act, and Sens. Angus King (I-Maine), Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), and Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) have introduced another option. The latter would, among other things, make explicit that the vice president does not have the power to overturn the Electoral College, offer a longer window for the “safe harbor” date allowing states to complete recounts or necessary investigations before certifying their results, specify grounds for members of Congress to object to the votes, and increase the number of backers needed to sustain an objection to electors’ vote. “Taken together, the proposed legislation would confront electoral subversion at both the state and federal levels by helping ensure that partisan politicians cannot substitute their own preferences for the judgment of the American people in presidential elections,” the senators write. It is likely that the bipartisan group of senators will come up with much the same list of priorities.

Back Then

The term “Electoral College” does not appear in the text of the Constitution itself, though the collection of electors that the Constitution dictates have always been collectively referred to in this way. (Merriam-Webster has a fascinating article on why this term is used.) If you took U.S. history in high school, you probably know that the Founders settled on the Electoral College as a result of a compromise between those who wanted a strict popular vote and those who didn’t want the American people to have any say at all in electing the president. Among the most compelling reasons for the compromise? The existence of slavery. James Madison preferred a popular vote but acknowledged it would be difficult to get Southern states on board given the presence of so many slaves. He wrote, “There was one difficulty, however of a serious nature attending an immediate choice by the people. The right of suffrage was much more diffusive in the Northern than the Southern States; and the latter could have no influence in the election on the score of Negroes. The substitution of electors obviated this difficulty and seemed on the whole to be liable to the fewest objections.”

In Other Voting News

- The Associated Press has a useful roundup of the bills in statehouses across the country that would expand criminal penalties for threatening election workers. “Nationally, we are seeing longtime experienced election leaders and their staffs leaving their positions for other work because they’ve had it — this is it, this has crossed the line,” Vermont Secretary of State Jim Condos told the AP.

- A Dec. 18, 2020, memo obtained by the Washington Post, advocated that Trump analyze National Security Administration data to prove foreign intervention in the 2020 election. The memo’s origins remain unknown, but was circulated among Trump allies.

- A third Republican county clerk in Colorado is under investigation for allegedly copying sensitive election data without authorization. Douglas County Clerk Merlin Klotz allegedly posted video surveillance of the county’s voting machines along with answers to a variety of questions on the social media site Telegram — an app popular with the far right. In the post, he appears to suggest he “took a full image backup of our server.” He has until Feb. 10 to respond to questions from the secretary of state.

- In a rare display of bipartisan support for an elections bill, a proposal to update New Mexico’s laws on poll challengers and expand voting options won unanimous approval in the state Senate this week. The bill requires counties to use vote centers that allow voters to cast ballots anywhere in the county, imposes limits on poll watchers, and updates cleaning requirements for the voter roll.

- After a Pennsylvania court struck down the state’s vote-by-mail law — which allows mail-in voting by any registered voter — the state’s Supreme Court has decided to hear the case. Arguments are scheduled for March 8 in Harrisburg. The law remains in force until the court issues its ruling.

- Officials in Pennsylvania are continuing to raise concern over the impact of the state’s delayed redistricting maps on their ability to prepare for the May 17 primary election. Mail-ballot applications are going out this week, but local election administrators still don’t know whom they ultimately will put on the ballots or what voters get which ballot.

- The numbers are out: The failed recall election of California’s governor cost taxpayers a cool $200 million. $174 million of that was carried by the counties, and the rest by the secretary of state’s office. Shockingly, that number is less than the originally estimated $278 million.

- A Republican candidate for Michigan’s state Senate advised his followers to “show up armed” at polling places if they serve as election observers. The candidate, Mike Detmer, has been endorsed by former President Trump. County officials advise voters not to do this, obviously.

- Minnesota Secretary of State Steve Simon has rejected a request by the Crow Wing County Board to audit the 2020 election. The county made the request after being lobbied for months by a group of citizens who had a “vibe” that the 2020 election had been stolen.

- A bill in West Virginia would make it a felony to knowingly vote twice in an election, a crime that is currently a misdemeanor. It appears to be sailing right through the Legislature.

Infographic of the Week

By Brianna Fisher, Votebeat fellow

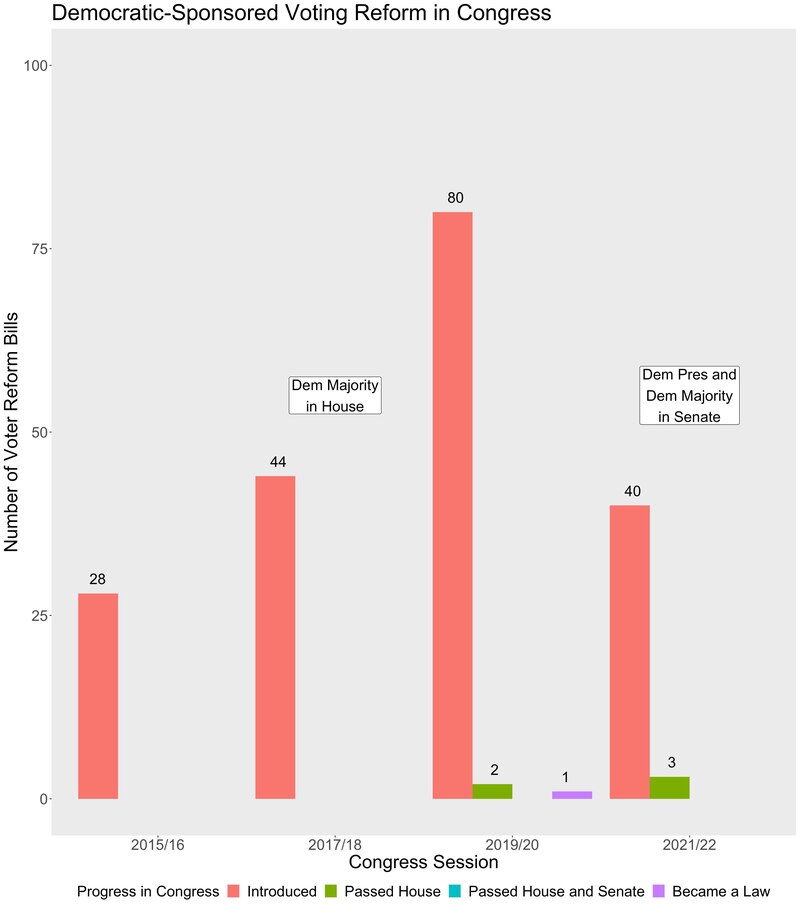

This week’s infographic looks at the volume of Democratic-sponsored voting reform bills introduced in Congress, starting in 2016. As you can see: The vast majority of these bills were introduced, and then very few progressed toward becoming law after that.

Even as Democrats increased their power in chambers of Congress and won the presidency, Democrats have made little progress in the space. In both the 2015-16 and 2017-18 sessions, no voting reform bills passed either the House or Senate. The 2019-20 session had the most success with two bills passing the House and one becoming law (S. 1321 Defending the Integrity of Voting Systems Act). In the 2021–22 session so far, three bills have passed the House only. Political observers’ theories on this track record range from GOP obstructionism to lack of Democratic unity to ineffective White House leadership to unwillingness of lawmakers to limit the scope of their bills.