A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

Senators tend to treat confirmation hearings for Supreme Court justices as political theater. And more so in the case of Ketanji Brown Jackson’s hearings last week: The Democrats have the votes to confirm Jackson without a single Republican vote, and her appointment will not materially change the political makeup of the court. But what really matters is that the confirmation of a Black woman to the nation’s highest court would be a ground shift, and Jackson’s elevation to the SCOTUS bench has implications for voting and democracy. Let’s talk about them.

Prior to her current position on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, to which she was nominated and confirmed last year, she was a U.S. district court judge for D.C. Most notably during that time, Jackson wrote the massive opinion that forcefully rejected former President Donald Trump’s argument that former White House counsel Don McGahn didn’t have to cooperate with the House as part of Trump’s first impeachment probe, concerning his treatment of special counsel Bob Mueller’s investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election.

“Stated simply, the primary takeaway from the past 250 years of recorded American history is that Presidents are not kings,” she wrote in the 2019 ruling. “This means that they do not have subjects, bound by loyalty or blood, whose destiny they are entitled to control.” McGahn did eventually testify, though it took two additional years of negotiations. His testimony painted a picture of a president who was increasingly erratic, and confirmed that McGahn was the source of the Washington Post’s reporting that Trump had asked him to fire Mueller. McGahn’s testimony was among the most impactful of the investigation and brought significant clarity to Trump’s bellicose position on Russia’s interference in the 2016 campaigns.

Jackson is known for writing long opinions, which she said as part of her testimony this week was consistent with her belief that judicial opinions should be as transparent as possible. This gives her a lot of space to explain her thinking. She took that liberty in a footnote in the McGahn case, beating up on Trump’s position that he had the unilateral authority to determine whether his subordinates at the White House could participate in a congressionally authorized investigation. That he was president did not afford him more leeway as to the actions of others, she said. “For a similar vantagepoint,” she wrote “see the circumstances described by George Orwell in the acclaimed book Animal Farm ... ‘All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.’ “

While on the appellate court, she joined an opinion rejecting Trump’s claim of executive privilege in late 2021 and allowed the Jan. 6 commission to obtain materials from the National Archives. They included talking points on voter fraud claims for the press secretary, Trump’s calendar on Jan. 6 and the days surrounding the insurrection, a memo related to lawsuits in states Biden won, and materials from Chief of Staff Mark Meadows documenting the day. By deciding in favor of transparency and executive accountability, Jackson and her colleagues enabled the fact-finding that will be necessary to protect elections and the legitimacy of the results.

“The events of January 6th exposed the fragility of those democratic institutions and traditions that we had perhaps come to take for granted. In response, the President of the United States and Congress have each made the judgment that access to this subset of presidential communication records is necessary to address a matter of great constitutional moment for the Republic,” the three-judge panel wrote. “Former President Trump has given this court no legal reason to cast aside President Biden’s assessment of the Executive Branch interests at stake, or to create a separation of powers conflict that the Political Branches have avoided.”

Jackson was vocal with her questions during the November 2021 oral arguments in this case. She argued that public confidence and the need to preserve records could supersede the “limited intrusion into executive confidentiality” necessitated by the commission’s request for the materials.

During her confirmation hearing this week, Jackson was asked about her views on voting rights by Sen. Alex Padilla, a Democrat and former secretary of state from California. “Can you just share …what you believe the role or responsibilities [of the] Supreme Court might be in protecting this fundamental right to vote and by extension, our democracy?” he asked. As is typical during confirmation hearings, Jackson didn’t show much of her hand, describing the landscape of voting law and drifting into a little word salad at the end:

Thank you, Senator. The right to vote is protected by our Constitution. > The Constitution makes clear that no one is to be discriminated against in terms of their exercise of voting. And the Congress has used its constitutional authority to enact many statutes that are aimed at voting protection. There are also laws that relate to ensuring that there is not only voting access, but ensuring that there isn’t fraud in terms of voting. > These concerns are embodied by various laws and provisions. And there are disputes at times over the concerns in the balances that are being made across the country relating to the exercise of voting, and those disputes come to court and then eventually to the Supreme Court that interprets the laws that pertain to the fundamental right to vote, which, as you say the Supreme Court has acknowledged is a fundamental right.

In summary: Voting is a right, and there are laws on the books to protect it and also to protect against fraud — and sometimes the Supreme Court has to make decisions given that legal landscape. There’s nothing more or less here than that. While technically an answer to his question, Padilla was probably looking for more than The Supreme Court sometimes makes decisions about voting.

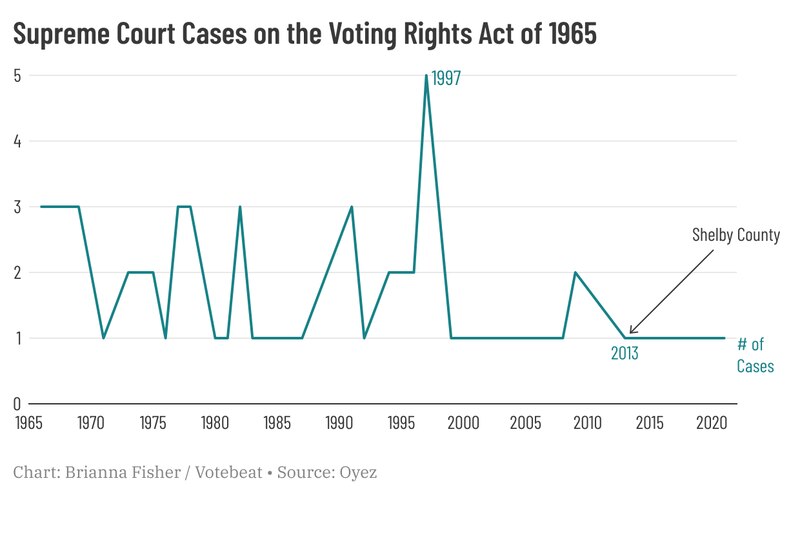

Jackson’s position on the court will not, however, make it much easier for progressives to win voting cases. Conservatives hold a 6–3 majority on the court, which will not change after Jackson is confirmed. In recent years, the Supreme Court has taken large bites out of the federal government’s ability to enforce voting rights — the Shelby County decision in 2013, last year’s Brnovich decision eviscerating Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, and the tossing of Wisconsin’s legislative redistricting maps only days ago — a trend Jackson will not be able to stop. Still, some believe her history of pragmatism on the bench and her résumé — stacked with unique-to-the-Supreme Court experience representing indigent clients — will go a long way in restoring public trust in the high court. “[Jackson’s] visibility to the country as a Black woman would result in greater faith in the judicial system itself,” Washington, D.C., congressional delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton told CNN. Black Voters Matter co-founder LaTosha Brown agreed, telling the network, “We need a voice on the Supreme Court that can weigh in on opinions from the perspective of those who’ve been deeply marginalized.”

Back Then

It is, of course, notable that Jackson was nominated for this position at all. In 1857, the Supreme Court ruled that Black Americans could not be considered citizens. This followed decades of whites in Northern states getting nervous about the rising number of free Black citizens who were increasingly eligible to vote as property requirements were eliminated. As abolitionist sentiment increased, so did hostile and virulent racism. A decade before the ruling, a delegate in New York said that “nature revolted” at the idea of Black voters casting ballots. Around the same time, a delegate in Indiana declared “The Black race has been marked and condemned to servility.” In Wisconsin, a delegate said that enfranchising Blacks would lead to a run on the state by freed slaves from the south. At the time, Black residents made up two-tenths of 1 percent of the population of the state.

In Other Voting News

- Speaking of the Supreme Court, let’s discuss this wild story about Ginni Thomas, wife of Justice Clarence Thomas. CBS and the Washington Post are out with a bombshell, showing that Ginni Thomas was in regular contact with Trump’s chief of staff, Mark Meadows. She asked him, repeatedly, to do everything he could to overturn the results of the election. It is far from the only time Ginni Thomas has caused a headache for her husband. We already knew, for example, that she’d attended the Jan. 6 rally but reportedly left prior to the start of the violence. The text messages surfaced as a result of the Jan. 6 commission’s investigation. A quick reminder that Clarence Thomas was the only dissenting vote in the case that allowed that commission to get these documents in the first place (the very 2021 case that Jackson heard in appellate court). Clarence Thomas has been hospitalized with an infection for the last few days and has remained silent on the issue. He was released Friday.

- The U.S. Supreme Court also narrowly tossed Wisconsin’s new legislative maps. The majority declined to block the state’s congressional maps. The decision comes only a month before candidates in Wisconsin are to begin gathering signatures to qualify for the primary ballot.

- The supply chain made Christmas difficult, sure, but wait until election season. Politico reports that local election officials are placing ballot and envelope paper orders months in advance so they stand a chance of actually getting their deliveries. Alaska is about to hold a special election to replace the late Rep. Dan Young, and a shortage of staff (among other issues) has pushed them to do an all-mail election. We are facing a shortage of everything, it seems.

- Those staff and paper shortages stand to be exacerbated by delays in redistricting. In Ohio, with six weeks until the primary, voting districts are still up in the air. The state’s Supreme Court has denied a request by Democrats to delay the primary.

- The counting and certification of an extremely narrow race for Lehigh County judge in Pennsylvania has been halted by a federal appeals court. A group of voters sued after the county refused to count 257 ballots that were missing hand-written dates next to the signatures on the envelope. Stephen Caruso of the Pennsylvania Capital-Star is out with an excellent explainer on the rest of the confusing legal quagmire the state finds itself in ahead of the midterms.

- Meanwhile, at least the state’s redistricting maps are settled (for now), and Votebeat partner Kate Huangpu of Spotlight PA recaps the process.

- A Senate panel in Arizona has approved a measure requiring ballots to be hand counted, even as one Republican (who voted for it!) admitted it was an impossible task. There would, for example, be 200 individual races to tabulate in Maricopa County alone. “I don’t see how that is possible,” said Sen. J.D. Mesnard. It isn’t!

- The Kansas Senate has approved a measure that would reduce the number of drop boxes in the state by 40 percent, hitting rural communities the hardest.

- The New York Times reports that more than 18,000 ballots were rejected in Texas’s most populous counties as a result of the state’s new voting law, which required voters to list identification numbers on the ballot envelope to prove their identities. The rejections disproportionately affected voters in Black areas of Harris County, the state’s largest county. North of there, outside of Austin, even Willie Nelson and his wife were affected by this chaos.

- The Department of Justice has sued Galveston County, Texas, over its commissioners court maps. It accuses the county of violating the Voting Rights Act when it carved up the commissioners court into four majority white districts.

Infographic of the Week

By Brianna Fisher, Votebeat fellow

Today, a graph of — *jazz hands* — context. Using data from Oyez, a digital archive of Supreme Court cases, I’ve created a graph that shows the number of Voting Rights Act cases heard before the court annually. As you can see, there was a big spike in 1997. This appears to be a coincidence rather than an isolated trend. Below, I break down each of the 1997 cases.

Young v. Fordice (March 1997) asked the court to decide whether Mississippi violated the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by implementing a new voter registration policy, the “New System,” without explicit approval from the U.S. attorney general. The court ruled that yes, this violated the Voting Rights Act, and Mississippi must submit the system to the attorney general for pre-clearance.

Abrams v. Johnson (June 1997) asked the court to decide if a Georgia district court’s redistricting plan violates the Voting Rights Act or Article I of the Constitution, guaranteeing “one person, one vote.” The court ruled that no, the district court did not violate the Voting Rights Act. They argued that the district had no obligation to preserve the three Black-majority districts, saying that the plan’s creation of only one Black-majority district would not violate the Voting Rights Act.

City of Monroe v. United States (November 1997) asked the court to decide if the city of Monroe, Georgia, is entitled to conduct elections under a state-law rule requiring majority vote to win, when the U.S. alleged that the city had not sought pre-clearance of the change from plurality voting as required by the Voting Rights Act. The court ruled that yes, Monroe can conduct the elections under the rule because the attorney general had approved and pre-cleared the default rule and could have decided it was harmful for the minority group within that period.

Foreman v. Dallas County (June 1997) asked the court to decide if Dallas County, Texas’s changed procedures for selecting election judges were exempt from pre-clearance under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. The court ruled that no, the changes were not exempt from pre-clearance even though the county exercised its discretion because the appointments were based on party power.

Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board (May 1997) asked the court to decide if pre-clearance must be denied under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act whenever a covered jurisdiction’s new voting “standard, practice, or procedure” violates Section 2 of the act. The court ruled that no, pre-clearance may not be denied just because a covered jurisdiction violates Section 2.