A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

I assume I wasn’t the only one who watched this week’s hearing before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee — which was supposed to be about violence against election officials — while suppressing the violent urge of wanting to throw my TV out of a window.

I hadn’t known, before the hearing at least, that the threats against election administrators were really about the vandalism, violent crime, and general mayhem that Republicans assert — to some skepticism — is on the rise in today’s United States. But don’t worry: U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz is here to tell me more.

“Welcome to the witnesses,” he said, making it obvious that, really, he didn’t care much about whether they felt welcome or not. He didn’t seem to actually want to hear from the assistant attorney general from the U.S. Department of Justice prosecuting election threats, nor from the election security lead at the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency.

Cruz wanted to talk about abortion.

He knew, of course, that this wasn’t on the agenda.

He simply didn’t care.

The Texas Republican called the Department of Justice’s focus on threats to election workers “political.” They were, after all, simply “threats.” No one has died, he said, pivoting immediately to the defacement of “pregnancy crisis centers” in several American cities. As he got going, staffers bustled up to display poster-sized pictures of boarded-up windows and paint-stained doors to aid their boss’s planned attempt to derail the hearing. Unfortunately, no one could stop him.

He threw intensely specific questions about pregnancy centers at witnesses who were supposed to be there to testify about threats against election clerks. Then, he closed. “I think you need to follow the law!” he barked at the witness from the DOJ, before pushing his microphone button and taking a theatrical sip from his paper coffee cup, apparently satisfied with his performance.

U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin, an Illinois Democrat, then read a statement. Like Cruz with his printed posters, Durbin had prepared. He denounced all forms of violence, just to cover his bases, and said “the nature and the purpose of this hearing is to address the undermining of the American election system.”

Thanks for the reminder. I guess we needed it.

Witnesses on the second panel stuck with the same theme. There were real election officials, like the secretaries from Michigan and New Mexico, and testimony from many more. But alongside came a former Trump-appointed DOJ official, a guy from a law enforcement legal defense fund, and another guy from a right-wing policy think tank. Fine, these folks said, election threats are bad. But guess what’s worse? Murder.

“In my opinion, there exists a much more dire and pressing crisis facing the American public, and that is the rising violent crime surging throughout our country,” said Michael Hurst, a former U.S. attorney in Tennessee. He, like Cruz, apparently believes the self-anointed Greatest Deliberative Body On Earth can’t possibly tackle threats to our democracy while crime is also popping off.

Not five minutes before Hurst spoke, Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, a Democrat, had told the senators about a December 2020 incident in which dozens of people gathered outside of her home, shouting threats at her and her family. It wasn’t the last time it would happen. “There is an omnipresent feeling of anxiety and dread that permeates our daily lives,” she said.

“Not long ago my son was standing in our driveway and found a stick. He looked at me and said, ‘Don’t worry mom, if the bad guys come again, I’ll get them with this.’ He’s 6 years old.”

That story isn’t surprising, I assume, to most people who read this newsletter. Not because you’ve heard that exact anecdote before, though you might as well have. I struggle to think of a state-level elections official who hasn’t been subjected to a barrage of threats and intimidation. The number of county-level officials I know who are not at least nervous on a daily basis is growing fewer by the day.

Republicans know that. They have sat through more than five panels on the very same subject so far this year. They have heard the testimony of Shaye Moss before the Jan. 6 Commission. Moss, who is Black, described “threats wishing death upon me, telling me I’ll be in jail with my mother and saying things like, ‘Be glad it’s 2020 and not 1920.’ ” They know that she, her mother, and dozens of other election officials were forced to leave their homes due to threats sparked by misinformation. They know hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars are being spent on additional security, significantly beyond what previous years have required.

This isn’t even the first hearing where they’ve attempted to distract from the issue at hand in the last month. Two weeks ago, the U.S. House’s Committee on Homeland Security held a similar hearing, also with election officials who were there to speak of the increasingly hostile environment. One of them was Neal Kelley, the retired elections director for Orange County, Calif., and current chair of the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections, who said he was “surprised at the tenor” of the hearing.

“Everyone was just jockeying to talk about their issue of choice, but this is a real issue,” he said. “God forbid something could really happen beyond threats. If you have someone going into a pizza parlor with a gun because of something they read on the internet, what stops them from going into a polling place?”

So, does an election official have to be killed or otherwise maimed in order for Cruz to talk about election officials during a hearing about election officials? Perhaps they’ll listen to the next three hearings on the same problem, and we won’t have to find out.

Back Then This Is Now

I struggled to find a tight history fact that was relevant to today’s newsletter, and then realized that was the point: This environment is completely unprecedented. There is no other time in American history in which election officials — the people who do the tedious and often backbreaking work of keeping this democracy (such as it is) afloat — have randos showing up at their door to make citizens’ arrests. And as we wrote about two weeks ago, this year is the first year that the National Association of State Election Directors conference has had to take such profound steps to keep participants safe. I can’t think of another time where a man who hadn’t even yet run a federal election became the subject of such profound misinformation about 2020, recently being forced to cancel a public event because of a bomb threat sent by someone more than 1,000 miles away. Routinely, Republicans pointed out the small number of overall successful convictions despite 1,000 reports of threats. But the effort to investigate such threats has only existed for just over a year, and the DOJ reports that 11 percent of them — more than 100! — are prosecutable as federal offenses. In so many ways, we’ve only just developed the tools to understand the depth of this problem. So I don’t have a comforting, disconcerting, or ironic fact for you this week. We’re all experiencing history as it is happening.

New From Votebeat Texas

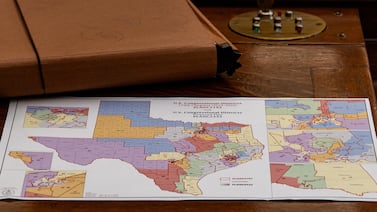

For more than a year, a coordinated group of Texas activists have mounted a statewide effort to further former President Donald Trump’s lies about the 2020 election: They’ve sent voters hundreds of postcards requesting personal information, questioned residents at addresses pulled from voter rolls, and examined thousands of ballots for unspecified irregularities. They’ve offered no compelling evidence of mass fraud, but the effort continues, and it’s deeply rooted in Tarrant County, Natalia Contreras reports.

New From Votebeat Arizona

- When David Frisk took over Pinal County’s elections in March after arriving from Washington state, he was the third director on the job in the past two years. He was greeted by a staff of one — in a department that should have had five full-time workers. Rachel Leingang reports on how turnover could have contributed to recent election errors.

- Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich investigated allegations that dead voters cast ballots in the 2020 election, and found only one real case out of hundreds of claims, he said in a letter to Arizona Senate President Karen Fann last week, Leingang reports.

- Fueled by Diet Coke and sporting an easy smile on the morning of the first big election he’d ever run, Maricopa County Recorder Stephen Richer brushed off mean tweets, misinformation, and angry emails over the course of a mostly smooth day that served as his first big test, Leingang reports.

New from Votebeat Michigan

Michigan’s smooth, low-turnout primary contrasted with a bizarre incident: Security had to eject a GOP poll challenger from a Detroit counting site because he was harassing election workers, Oralandar Brand-Williams reports.

In Other Voting News

- The Pennsylvania Supreme Court upheld the state’s mail-voting law, rejecting a challenge from Republicans who asserted the state Legislature didn’t have the authority to allow voters to cast mail ballots without an excuse, Spotlight PA reports. The 2019 law, known as Act 77, passed with bipartisan support and represented a major expansion in voting access.

- New audio recordings of meetings show the Republican National Committee is working closely with GOP activists and advocates, especially lawyer Cleta Mitchell, to train poll workers in battleground states for the upcoming midterm elections. The recordings, which the group Documented provided to Politico, show the party is relying heavily on activists who have spread election conspiracy theories.

- Guy Wesley Reffitt, the first defendant to go on trial on criminal charges related to the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, was sentenced to seven years in prison. It’s the longest sentence of any defendant to date in cases related to the Capitol riot, and could set a precedent for others.

- Kansas Secretary of State Scott Schwab, said he’s skeptical that a county sheriff received more than 200 claims of election fraud related to the 2020 presidential election, a number Schwab said would far outstrip the number of complaints he received statewide.

- Local officials in Nye County, Nevada, after hearing from witnesses and residents peddling election conspiracy theories, have voted to hand-count ballots going forward. The Associated Press reported the decision has thrown the county into disarray, and the county’s longtime clerk, Sam Merlino, said the decision prompted her to submit her resignation.

- Republicans who dispute the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election and have made unsupported allegations of fraud won primary battles this week for offices with authority over elections in Arizona and Michigan, the New York Times reports.

- Activists seeking evidence of voter fraud or election irregularities are swamping elections offices around the country with public records requests, overwhelming their staffs and consuming massive amounts of resources, Reuters reports.

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org.