Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free weekly newsletter to get the latest.

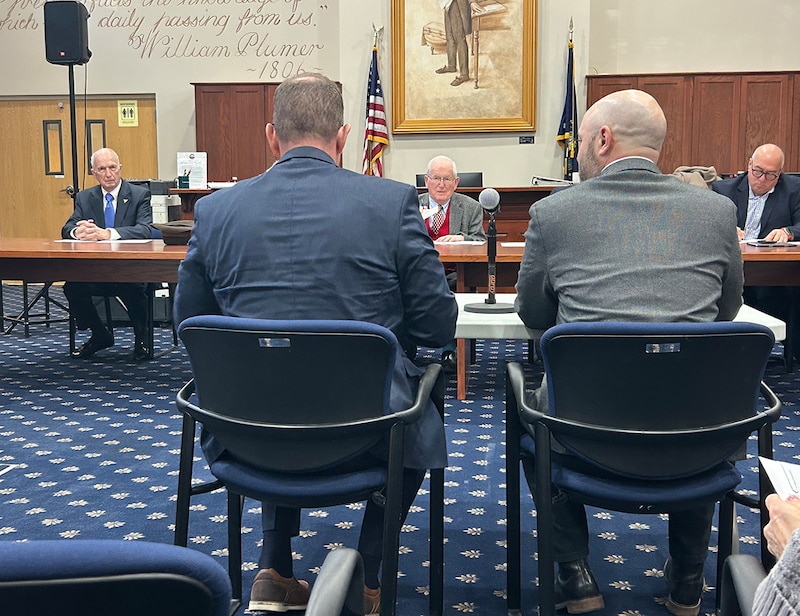

CONCORD, N.H. — On a freezing December day, Liberty Vote executive Robert Giles sat before the New Hampshire Ballot Law Commission to answer questions about a familiar company operating under an unfamiliar name.

Until October, the company had been Dominion Voting Systems — one of just two vendors certified to sell voting systems in the state. Then, it was sold to a former election official named Scott Leiendecker and rebranded as Liberty Vote. State regulators required to sign off on changes wanted to know more about who and what, exactly, they were signing off on.

As one ballot law commission member pointed out, in New Hampshire, “when we give somebody a liquor license for a little restaurant, they have to go through quite a bit of a background check before we’re able to provide that. So I think we’d like to know a little bit more.”

Secretary of State David Scanlan, a Republican, said he and others had “some really hard questions” for the company. A commission member had a fundamental one.

“Why did he acquire this company?” he asked, referring to Leiendecker.

“You would have to ask him that question,” Giles replied.

They would hardly be the first. Election officials have been wrestling with that question since the announcement that Leiendecker — who previously had founded a major electronic pollbook company — had purchased Dominion. The purchase immediately vaulted the former Republican election official from St. Louis, little known to the public, into one of the most powerful players in American elections. Whether he can stabilize a company that provides voting systems to roughly a quarter of the country — and has been battling conspiracy theories since 2020 — is an open question.

‘I felt I needed to do something about it’

In a January interview with Votebeat, Leiendecker said Dominion had a good product, employees, and customer base but needed a new owner who understood and cared about election technology and elections — an area where he has a long track record. “I felt I needed to do something about it. So, you know, here we are.”

He also said that he wondered, “if not me, then who would?”

That’s a good question, too. Dominion came with considerable baggage. In the wake of the 2020 presidential election, President Donald Trump and his allies alleged Dominion systems deleted or switched votes, but no evidence emerged to support that. The claims were repeatedly debunked, including by Republican officials. Fox News, Newsmax, and former Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani settled defamation claims brought by the company, in Fox News’ case for $787 million.

But the false allegations hurt business, the company said, and some places canceled or rescinded contracts and selected other vendors. In 2023, after the Fox settlement, Dominion’s former CEO told Time that the allegations had “basically put us into a death spiral” and said a customer had described it “as the most demonized brand in the United States.”

Dominion was a distressed business, Leiendecker acknowledged in December to the St. Louis Business Journal. But in the interview with Votebeat, he stressed that he believes there’s a path forward, despite the challenges. “Can we turn this around? And I believe that we can,” he said, adding that he’s received a lot of encouragement from election officials.

There are big challenges, as well as signs Trump administration officials continue to focus on election equipment in general and Dominion specifically. Since returning to the White House, Trump has continued to rage against voting machines. In addition, officials reportedly contacted local officials in Colorado and Missouri, unsuccessfully asking to examine Dominion equipment used in the 2020 election. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence took custody of voting equipment in Puerto Rico last year. And the White House has said the U.S. Department of Homeland Security is expected to deliver a report on the cybersecurity of voting systems.

Leiendecker said Liberty Vote has not directly heard from officials with the departments of Justice or Homeland Security regarding the planned cybersecurity report or any requests to review the company’s equipment.

He’s happy to answer questions from people with concerns, he says, but he hopes that if election officials and others prove the system is secure, people will listen. “Our election officials do a great job. They know what they’re doing,” he said. He said he hopes the public will be reassured by learning more about the checks in place, such as, for example, paper ballots that can be audited and checked against machine counts to ensure they are accurate, and also said the election process needs to be as transparent as possible.

As for Trump’s views, Leiendecker chooses his words carefully. “The president, you know, has an opinion, and he has a very big opinion when it comes to it, right?” he said. “His views need to be heard, obviously, but I hope that he listens to” election officials.

‘Can we turn this around?’

Dominion was hardly the first election technology company to get consolidated into another one, including after controversy. In 2003, for example, Diebold’s CEO, a fundraiser for former President George W. Bush, said he was “committed to helping Ohio deliver its electoral votes to the president next year,” sparking worries about whether the machines could be trusted; he later called his comments a “huge mistake.”

There was ultimately no evidence of wrongdoing in connection with the company’s equipment, but that and other issues prompted it to sell its voting machine division. Many of those Diebold assets ultimately went to Dominion.

“Now we jump ahead to Trump’s time, and now the Republicans think that the same system that was created by Diebold that was then sold to Dominion is now going to rig votes against them and for Democrats,” said Terry Burton, the co-director of the Wood County Board of Elections in Ohio.

“And now that it’s been sold again, now we’re starting to see the first vestiges of the swing back.”

Burton was referring to the focus on Leiendecker’s Republican background after he acquired Dominion. The press release announcing the company’s sale described it as “a bold and historic move to transform and improve election integrity in America” and echoed language used by Trump and other conservatives, including calls for hand-marked paper ballots.

The announcement — managed by a Republican-aligned communications firm and hastily put together (Leiendecker had expected to have more time) — sparked full-throated fears that the company was now an arm of the Republican Party. As a result, some expressed concern that the left would start embracing conspiracy theories about the company previously pushed by the far right.

At the time, Matt Crane, executive director of the Colorado County Clerks Association, told Votebeat that clerks were initially “very upset” about the announcement’s tone and the initial uncertainty about what might change. Some Colorado clerks issued public statements, and Crane arranged a meeting for clerks to talk through the changeover with Leiendecker. Since then, Leiendecker has followed up individually with many of them, and tensions have “calmed down,” Crane said.

Leiendecker says he hadn’t expected the response and doesn’t think of himself as partisan. He stressed his long track record in the election technology business and as a former election official, pointing out he understands and has worked to meet the challenges of the profession. He also stressed the positive responses he’s gotten as he’s spoken to election officials.

People in the industry said the launch complicated an already fraught and closely watched sale. Mark Lindeman, the policy and strategy director for Verified Voting, a nonprofit organization that tracks voting equipment use, said he was also distressed to see news coverage around the sale of Dominion focus on Leiendecker’s partisan background.

“Our judgments should not be based on our gut feelings about the politics of anyone involved in the companies. It’s just not a reasonable way to go,” he said. “We have to look at performance. So that’s why we have voting system certification, that’s why we have pre-election testing. That’s why we have post-election audits, right? I hate to see this continued swerve into partisan speculation.”

Leiendecker says existing wells of trust from his long track record in elections and past work helped him recover from the rocky rollout: His other company, KNOWiNK, is the country’s leading manufacturer of electronic pollbooks, the systems used to check in voters at polling places, and the company’s pollbook was the first to be certified by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

As of the November 2024 election, Dominion provided election equipment to more than a quarter of registered voters in the U.S., according to Verified Voting — more than all but one other vendor, Election Systems and Software. Together, Leiendecker’s two companies provide election equipment to thousands of jurisdictions led by officials from both parties.

Among those publicly vouching for him: Nevada Secretary of State Francisco Aguilar, a Democrat who said Leiendecker was responsive and attentive as the head of KNOWiNK when Nevada transitioned to a new voter registration management system.

Leiendecker says election officials seem relieved to know Liberty Vote has a new, committed owner and encouraging about its plans for the future, though he’s assured them that little or nothing is changing immediately. In 2026, Liberty Vote’s focus is making sure the midterms run smoothly for clients, he said.

Plans include federal certification for new voting system

Leiendecker is slowly settling in and figuring out ways to streamline the work his companies are doing.

Liberty Vote is still headquartered in Denver, where Dominion was based. KNOWiNK is headquartered in Leiendecker’s home base of St. Louis and will remain a separate company, Leiendecker said, though he said technology staff members at the two companies will be looking for ways to make the products work more seamlessly together.

Liberty Vote recently hired former Washington Secretary of State Kim Wyman, a Republican who was also a senior election security adviser at the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, to handle government affairs. It also hired a firm with strong Missouri ties earlier this month to lobby the federal government on election security, federal lobbying disclosures show; a Liberty Vote spokesman said it “will support our ongoing work to serve election officials nationwide and advance the future of American elections.”

In late November, Liberty Vote submitted a system, called Frontier 1.0, to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission for certification under the latest set of voluntary voting system guidelines approved by the agency, a set of standards widely referred to as VVSG 2.0. The submitted system is a version of Dominion equipment currently in use, but updated to meet the criteria of the newer guidelines, company officials said.

The submission is an important benchmark for the company, since many jurisdictions planning to purchase new equipment will want it to meet the most recent set of federal guidelines, or be in the process of getting certified under those guidelines (the company is also one of six competing for the biggest available contract at the moment, from Louisiana). So far, the U.S. Election Assistance Commission has certified systems from only two manufacturers as meeting the VVSG 2.0 guidelines, and others are still in the testing process.

Dominion’s existing agreement with New Hampshire, which Liberty Vote has now inherited, calls for the company’s system to receive certification under VVSG 2.0 by the end of 2026. At the December meeting, Giles told the New Hampshire Ballot Law Commission that after discussions with the testing laboratory, the company believes it can finish the process in about eight to nine months; New Hampshire officials later said the laboratory confirmed that certification this year is a reasonable expectation.

The New Hampshire commission must sign off on any changes to the technology currently certified for use in New Hampshire. And each state has different requirements for voting machines to be approved for use in the state, though many require either federal certification or testing in federally approved laboratories.

Among the changes in the system submitted for certification: Liberty Vote, and just about every other manufacturer, is moving away from using barcodes or quick-response codes in ballot tabulation, something Trump sought to prohibit in his March executive order on elections.

Election officials, too, are worried about how to rebuild public trust in elections and election technology. As New Hampshire’s Scanlan points out, voting equipment is one area where it’s hard to be transparent. At some level, people have to trust that the voting machines in use to allow local election officials to quickly and reliably tally large numbers of ballots and report results quickly are doing so correctly.

Pre-election testing and post-election audits, including hand-count audits, are part of how election officials provide evidence that tallies are correct, he said.

“If they question whether the machine is counting votes accurately, it’s not an easy thing for any election official to explain,” Scanlan said, other than to stress, “we have these safeguards in place: testing, audits and just other ways to verify the accuracy of the results.”

Carrie Levine is Votebeat’s editor-in-chief and is based in Washington, D.C. Contact Carrie at clevine@votebeat.org.