Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

A federal judge will soon decide whether to allow two new Arizona laws to go into effect that would require officials to investigate the citizenship status of all voters who haven’t yet provided proof of citizenship, and to regularly check the voter rolls for noncitizens.

An army of voting rights groups, backed by the U.S. government and D.C.-based Elias Law Group, have lined up to challenge the laws, arguing they could potentially lead to eligible voters having their registration canceled and may create an uneven and discriminatory system across the state.

The laws, HB2492 and HB2243, would subject to investigation up to about 32,000 Arizona voters who have not yet provided documented proof of citizenship for their voter registration, along with future voters who can’t provide documents proving their citizenship.

Voting rights advocates told U.S. District Court Judge Susan Bolton that the laws would require officials to regularly use faulty or old databases to check citizenship that would likely incorrectly flag citizens, resulting in the disenfranchisement of eligible voters and an uneven system around the state. “It could have a chilling effect on our community,” Joe Garcia, vice president of public policy for Chicanos Por La Causa, a nonprofit that advocates for Hispanic communities, testified on the first day of the trial.*

This is a uniquely Arizona case. That’s because federal law doesn’t require documented proof of citizenship — such as a driver’s license or tribal ID number, passport, or birth certificate – when registering to vote in federal elections. Arizona is one of just a handful of states that have enacted laws requiring this such proof, and it is the only state where the law is actively enforced, according to information provided by the National Conference of State Legislatures and other sources.

A 2013 U.S. Supreme Court case found that while Arizona could require voters to provide this proof for state and local elections, it had to allow people to vote in federal elections even if they didn’t provide the documentation. This has created a system in the state by which if someone registers to vote without proof of citizenship, they are designated a “federal-only voter” and sent a ballot with only federal races, such as the presidential and congressional races.

That’s why the state has about 32,000 voters who haven’t provided proof of citizenship and thus, are only entitled to vote in federal races.

The new laws were signed by Gov. Doug Ducey in 2022 but never went into effect because of the pending legal challenges. Bolton issued a preliminary ruling in September that decided some of the most significant portions of the laws won’t stand. That includes rules that would have blocked Arizona voters who don’t provide documented proof of citizenship from voting for president or by mail.

The trial — expected to take up to 10 days— is considering the portions of the law not yet addressed by that preliminary ruling. That includes new and complex rules for how the secretary of state, attorney general, and county recorders must investigate and regularly check voters’ citizenship status, and then cancel registrations of those they decide are not citizens.

The laws also require voters to provide their birthplace and documented proof of their address.

The judge’s preliminary decision means the remainder of the case turns on potential impacts that are difficult to prove because they haven’t happened yet — risks such as using bad data to incorrectly flag eligible voters who might miss the chance to remedy the problem before their registration is canceled, or an election official who unfairly targets certain voters.

Kory Langhofer, attorney for the Republican National Committee, which is defending the laws alongside Attorney General Kris Mayes and Republican legislative leaders, questioned on Monday why a citizen wouldn’t have any one of the many different ways to prove citizenship, such as a driver’s license, birth certificate, or tribal ID card.

Langhofer pressed voting rights organization leaders who took the stand over whether they have been able to identify any citizens who don’t have documented proof of citizenship. Out of three leaders questioned, only one said he had found such a situation — and he wasn’t able to provide particulars.

For their part, though, the state leaders defending the laws have so far not provided any evidence to the court showing that noncitizens voting has been a widespread problem in Arizona.

Janine Petty, Maricopa County’s senior director of voter registration, told the court that sometimes the county will find out about a noncitizen on the voter rolls when that person is summoned to jury duty and indicates in their response that they are not a U.S. citizen, and that information is forwarded to the county. But Petty did not indicate how often this happens, and the county did not immediately respond to a request for this information.

Secretary of State Adrian Fontes, who attended the trial Tuesday morning, said in an interview that any time laws are enacted increasing the burden on the voter, “it increases the possibility a voter will be denied.”

Arizona Republican lawmakers and conservative groups have long believed that the lack of requirement to show proof of citizenship could allow noncitizens to vote.

Meanwhile, voting rights groups say that the issue is not that federal-only voters are noncitizens; it’s that they don’t have, or can’t easily obtain, documented proof of their citizenship.

Frequent voter citizenship checks

The bifurcated system of “federal-only ballot” voters gives the state a list of voters to target for citizenship investigations.

For example, when someone registers to vote using a form for federal-only voters, HB2492 requires county recorders to “use all available resources” to verify their citizenship. This includes a few steps that county recorders already take when registering voters, such as checking what type of driver’s license the voters have, since noncitizens are given a particular type of license, and checking a federal system that tracks citizenship status of U.S. residents.

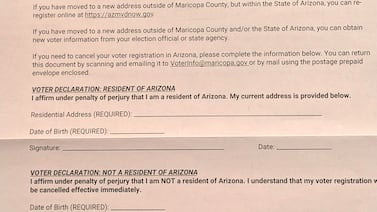

But when recorders do the driver’s license check when someone registers and find someone has a noncitizen license, they notify the voter about their lack of proof of citizenship and give the registrant until the next general election to provide the documentation before canceling their registration. Until then, they are placed on a suspense list and not allowed to vote. Under the new law, the registration would be immediately canceled without notice.

The law also states county recorders must use any databases they can access to attempt to check citizenship — which voting rights groups worry would prompt recorders to use unofficial or faulty databases to target voters in a political or potentially discriminatory manner, such as information submitted by grassroots groups.

In a June 2022 email to county officials across the state, Maricopa County Recorder Stephen Richer expressed concern about this when asking about the status of a related bill, according to a copy of the email shown in court on Tuesday.

“Does this get rid of the situation whereby any person can submit us lists that we then have to check? E.g. hi I used my super secret research program to figure out that these 300,000 people are not citizens. Please check the citizenship of every single one of them right now,” Richer wrote.

HB2243 requires county recorders to check citizenship of voters they have “reason to believe” are not U.S. citizens. Garcia said he believes this is meant to unfairly target new citizens, especially Latinos.

“It could be a last name that would be considered to be suspicious,” Garcia said.

The vague requirements are particularly striking because if an election official doesn’t follow the new laws, they could be found guilty of a felony, which Petty, the Maricopa election official, testified on Monday worries her colleagues. There is little guidance for what specifically recorders have to do to follow the law and no guidance on what might legally be a legitimate reason to believe someone is not a citizen.

State elections director Colleen Connor testified Tuesday that she believes any additional criminal sanctions in the law would add to the fears of doing their job, and add to the difficulty of retaining officials in an already volatile environment.

Voting rights groups are worried about another requirement for the Secretary of State’s Office to do a monthly comparison of the state’s Motor Vehicle Department database with the state’s voter rolls, to check voters’ license type — just as recorders do when someone registers to vote. In the case of these and other regular voter roll checks, the new law would give the voter 35 days to provide proof of citizenship.

Petty said, right now, when a voter registrant is notified that they are missing documentation, these registrants frequently do eventually provide proof of citizenship – and therefore are allowed to vote.

Another state, Texas, has found driver’s license type to be an inaccurate way of identifying noncitizens on voter rolls. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton in 2019 gave counties lists of individuals on the voter rolls who had the type of license given out to noncitizens. But when counties looked into each case, election officials realized that many of them registered after naturalization, and were citizens.

If Bolton rules quickly and allows these portions of the new laws to stand, they could apply before the 2024 presidential election to people registering to vote and already-registered federal-only voters.

*Correction, Nov. 9: This article originally misstated Joe Garcia’s title. He’s vice president of public policy at Chicanos Por La Causa, as well as executive director of Chicanos Por La Causa Action Fund.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.