Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Arizona’s free newsletter here.

WILLCOX, Ariz. — Peggy Judd knew exactly what she needed to do.

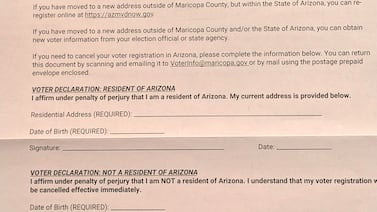

Judd, a Republican on the board of supervisors in Cochise County, Arizona, had to vote yes Wednesday on whether to certify the county’s presidential election results. If she didn’t, she would be not only breaking the law, but also violating the terms of her plea agreement.

That’s because, two years ago, after the 2022 midterms, she made a different choice. She and another Republican supervisor voted to delay the certification of that election past the legal deadline.

That decision made her one of a handful of local Republican officials around the country who unsuccessfully tried to halt or delay certification of an election. It also upended Judd’s life.

As she prepares to leave public office at the end of the year, she’s still reckoning with the consequences. And the county, a rural region in the southeastern corner of the state along the Mexican border, is still working through the distrust, turmoil, and national attention that came with Judd’s vote.

After the vote to delay, State Attorney General Kris Mayes launched an investigation into Judd and fellow Supervisor Tom Crosby. A grand jury later charged them with two felonies — conspiracy and interference with an election officer.

Judd initially fought the charges, and amassed $70,000 in legal bills, she told Votebeat in an interview Tuesday. She collected contributions to help pay the tab, including, she acknowledged for the first time, $5,000 wired from the Legal Offense Fund of MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell, who has promoted false theories about elections.

But despite promises from GOP activists and leaders to help anyone who bucked the system, most of the burden fell on her.

Judd, 62, signed a plea agreement last month admitting that she failed to certify the election as required by law. She was sentenced to 90 days of unsupervised probation.

That means that if she didn’t certify this election on time, she could be jailed.

Crosby, for his part, has pleaded not guilty, and his trial is scheduled for January.

Feeling betrayed: ‘I don’t want to be a Republican anymore’

Judd, a former state representative, is preparing to sell her house to her daughter, mostly because she needs money to pay her legal bills. Judd moved in with her mother this summer.

She said the local Republican Party she had helped nurture since the Tea Party movement began in 2008 has turned against her. She doesn’t feel welcome at the local GOP meetings now, she said, and has faced criticism for not going all the way on the effort to hand-count ballots and block certification. She said she plans to unregister as a Republican “soon.”

“When I was behaving, they were very kind to me,” she said. “But the minute I was saying ‘No, wait, whoa,’ then they hated me, like immediately. And that’s why I don’t want to be a Republican anymore.”

Even so, sitting at her sister’s pizza restaurant in Willcox the afternoon before the vote, she said she felt tortured by the thought of voting yes on certification the following morning, because Cochise did experience problems counting ballots.

“So much is going wrong,” she said.

A local reporter had just called her to tell her that the elections director had made a mistake when preparing the hand-count audit of results. And the county had mechanical problems with its tabulator while tallying votes during the initial count.

Judd knew the mistakes did not affect the final vote count. And because Donald Trump won the presidency, Judd said, the community wasn’t claiming fraud this time, or pushing her not to certify.

Still, she said she wanted to be deliberate about her vote. Certifying an election is a ministerial duty in Arizona, not a discretionary one, but she said she didn’t want to vote to certify just because she was obligated to. She wanted to be able to tell her community affirmatively that, despite the mistakes, the election should be certified.

She had been all day waiting for the elections director to send her a post-election report that might help her understand exactly what challenges election officials dealt with during the election, and how they resolved them.

She checked her email inbox one more time. But there was nothing there.

The day before the vote in 2022

Even before her vote not to certify the 2022 midterm election results, Judd was tangled up in lawsuits and drama over how Cochise County would handle them. For months, she and some other elected officials pushed for a full hand count of ballots. A judge blocked the plan, finding it would be illegal under state law.

Around the same time, Crosby and Judd conferred with a private lawyer — separately, they say — outside of a public meeting. They asked him to sue the county’s elections director personally for refusing to hand over the ballots for an expanded audit.

Mayes determined later that the two supervisors’ meetings with the outside lawyer had violated the state’s Open Meetings Act.

Activists also asserted that the voting lab that certified the county’s ballot tabulators had not been properly accredited, a claim that the Arizona Supreme Court had already rejected.

Crosby and Judd said they wanted more information on those claims and voted on Nov. 18 to delay the certification vote until the last day allowed in state law, Nov. 28.

Shortly afterward, the state elections director sent supervisors a letter from the U.S. Elections Assistance Commission confirming that the machines were properly certified.

Nonetheless, Judd said that on the day before the Nov. 28 vote, she met with two activists making the claim. She said she was helping them prepare to present at the supervisors’ meeting the next morning.

When those activists weren’t allowed to speak at that meeting, Crosby and Judd again voted to delay certification — this time, until past the county’s deadline to certify under state law.

Then-Secretary of State Katie Hobbs sued, and a court forced Cochise supervisors to certify later that week, allowing the secretary of state to still meet the deadline for statewide certification.

Judd this week said that no one on her staff had advised her of the county’s statutory deadline to certify, or that her vote to delay meant the county would miss it. But fellow Supervisor Ann English, the board’s only Democrat, says the supervisors were warned of the deadline.

Judd also said she had always intended to certify the election. While she had doubts about the fairness of elections elsewhere, she said she always knew Cochise County’s elections were fair.

What were Judd’s intentions?

A grand jury connected Crosby and Judd’s votes to delay certification with their earlier push for hand-counting all of the county’s ballots, and accused them of an illegal conspiracy to delay the election results.

Judd was putting out Christmas decorations with her family when she got a phone call telling her she had been indicted. She said she was surprised and especially wanted to push back on the idea that she conspired with Crosby. Judd said she never spoke to Crosby outside of public meetings, even about the lawsuit against the county’s elections director.

Judd’s sister, Cindy Chaffey, drove her to Phoenix for her arraignment in December 2023 and described Judd as “really struggling” with the charges against her at that point.

She said Judd is best known in the community not for the election drama, but as a longstanding public servant — one who goes out of her way to help others. Judd, she said, wanted to prove to the community that the county’s election was fair and believed her actions would allow that to happen.

“Because everything she does is with a good heart and with good intentions,” she said.

Not everyone saw Judd’s actions that way.

Sitting at R&R Pizza, Judd puts her phone on the table and replays a voicemail that arrived the day after her Nov. 28 vote to delay the results. The man’s voice on the recording tells her she is “election-denying, crazy, psychopathic anti-American to your very core, for denying people their rightful need to vote.”

“Hopefully you both get hit by semi-trucks,” the voice says, referring to Judd and Crosby. “Get cancer, suffer immensely, and die before the end of the year.”

Judd said she cried when she got that message, and regrets that her staff received messages like that, too. Criticism came from other members of the community as well, especially after Crosby and Judd’s actions prompted the resignation of the county’s well-regarded elections director, Lisa Marra.

English, the Democratic supervisor, said she is disappointed that Judd could get off with “a slap on the wrist.” English said she believes Judd and Crosby should also be held accountable for violating public meeting law.

Judd denies that she did so.

Surprise turned to doubt in 2020

This summer, prosecutors with Mayes’ office questioned Judd about her choices in what Judd called a “free talk” that preceded the plea agreement. She said she was honest when they asked her who had influenced her actions: It wasn’t Lindell, or anyone like that, she said. Mostly, it was her husband, Kit Judd.

Judd grew up in Willcox, and she and her husband raised their family there. She helped organize the Tea Party movement in Cochise, and later served as a state representative.

She and her husband were always Republican, but she said she thought of herself as independent-minded and at one point, voted for Democrat Barack Obama. That’s not something she told her husband about, she said.

But she remembers waking up the day after the 2020 election, surprised that Trump had lost. That surprise quickly turned into doubt about the fairness of the election.

And on Jan. 6, 2021, she was at the rally in Washington, D.C., when rioters broke into the U.S. Capitol, though she said she was with her kids and grandkids and nowhere near the building. She has not been charged in relation to what happened that day. She said she condemns the violence.

During the period after the 2022 election, she was caring full-time for her husband, who had become ill. She attended meetings online and voted from home, with him there, and said his opinions influenced her votes.

Kit Judd died in early 2024.

When trying to decide whether to take a plea agreement, she said she consulted privately with a regional leader in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, of which she is a lifelong member. He asked her if what she would be admitting to — delaying the results — was the truth. She said it was.

Upon signing her plea agreement, Judd said she felt Mayes launched her investigation for political reasons.

But a week after Judd signed the plea agreement, she said, Mayes came to Cochise County for the opening of the Oletski Border Operations Center. Judd said she approached her for a conversation and found her to be kind. Judd said the talk prompted her to think of Mayes as “more of an ally than an enemy.” Mayes’ spokesperson confirmed the two women spoke, but couldn’t confirm what was said.

Judd said her lawyer will ask the judge who heard her case to end her probation early. She wants a break from holding office for four years, she said, but isn’t ruling out running for supervisor again after that.

She wants to go on a Mexican cruise in January. She plans to try to get approved for a church mission trip later in the year.

First, though, she needed to vote on certifying the 2024 election.

On Wednesday morning, Judd showed up to a nearly empty meeting room. No one from the public spoke before the vote, despite the mistakes that occurred while counting ballots. The elections director had, by then, posted a full report of what occurred, and recommendations for improvements in future elections.

The team was new this year, since Marra’s departure has made it hard for the county to attract and keep elections directors. Joe Casey, associate county administrator overseeing elections, said in an interview that they were learning as they went.

When it came time for her vote, Judd thanked the elections team for “hanging in there” and “putting up with all my questions.”

“You allayed my fears,” she told them.

English and Crosby also thanked the staff. And then, they voted unanimously to certify the results.

“Yay,” Judd said immediately after. “Does it feel like we should have confetti or something?”

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.