Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Michigan’s free newsletter here.

Sometime in the hours after last week’s election in Hamtramck, officials who weren’t involved in elections walked into the city clerk’s office, a space that’s supposed to be a secure place to keep ballots.

That revelation has thrown the outcome of the Michigan city’s entire election into doubt, including an exceedingly close mayoral race.

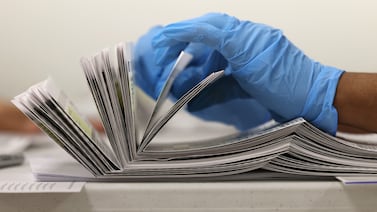

A total of 37 absentee ballots were initially unaccounted for on election night but were later discovered in the clerk’s office, opened but not yet tabulated. But since those ballots were not secured and could have been accessed by others, it’s currently up in the air whether they will be included in the election’s final totals.

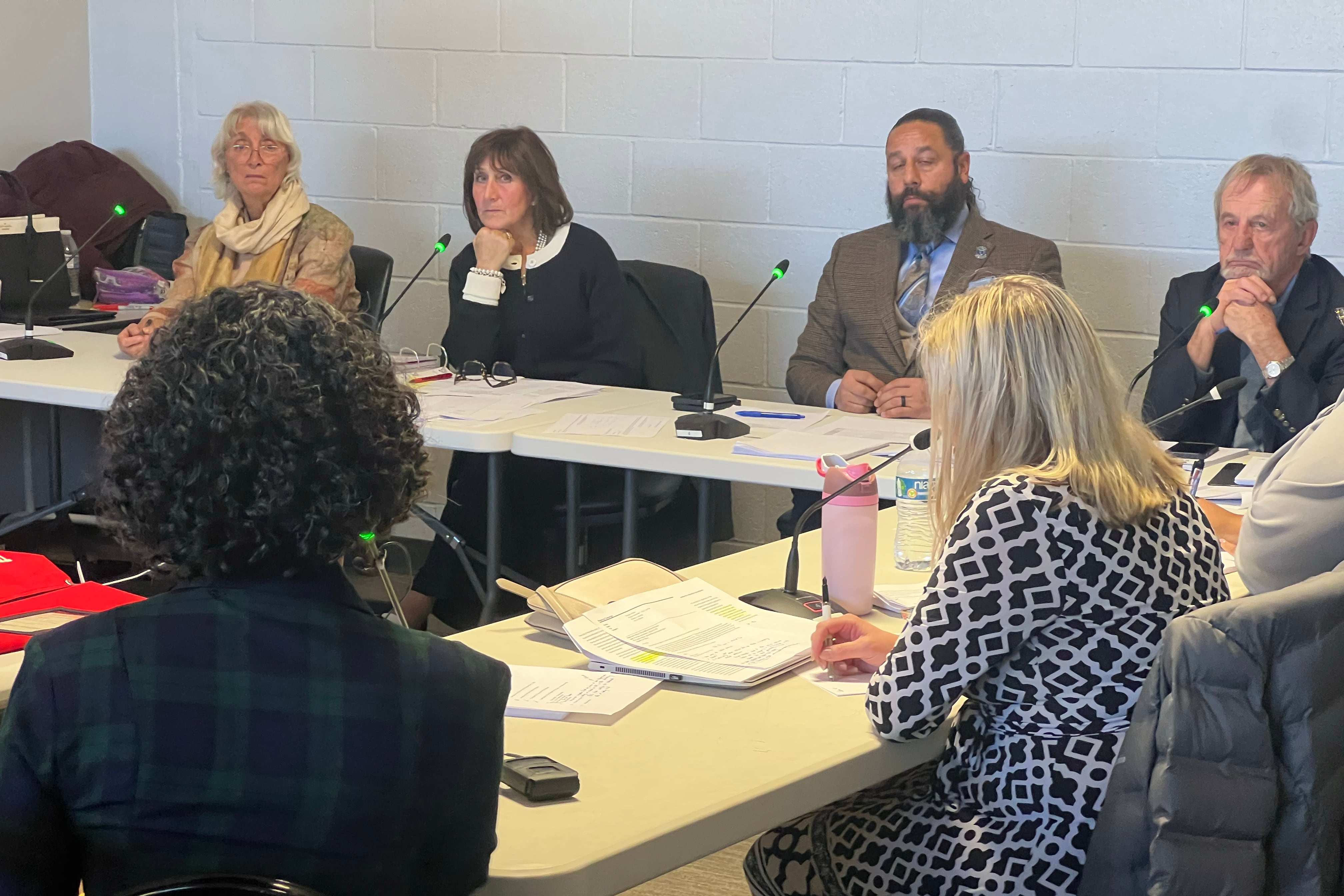

The fate of the 37 ballots now rests with the Wayne County Board of Canvassers, which deadlocked on the decision Thursday and put off a resolution until Friday. City officials’ breach of the ballots’ chain of custody — a core safeguard in election law — has cast new doubt on the city’s election system, which is already under scrutiny amid ongoing criminal investigations and unusually high numbers of corrected absentee ballots.

How the canvassers rule on the 37 ballots could affect who wins the open-seat mayoral election in Hamtramck, a city of about 28,000 that borders Detroit. According to unofficial results, engineer Adam Alharbi currently leads City Council member Muhith Mahmood by only 11 votes.

Ballots discovered after the election

City Clerk Rana Faraj told the board of canvassers on Thursday that her records showed a 37-ballot discrepancy on election night but that no one knew where the ballots were. They were found the next day in the clerk’s office, opened but still in their envelopes. When the discovery was made, the clerk immediately sealed the ballots in a secure envelope and brought them to the county, Faraj said.

The city clerk’s office is normally a secure space, so the discovery did not immediately raise questions about the ballots’ validity. However, Faraj said, her staff later realized several city officials, including interim City Manager Alex Lagrou, had entered the office while the ballots were there.

It’s unusual for non-election officials to go into a clerk’s office around an election, and it is not clear why they did so. Lagrou could not immediately be reached for comment Thursday.

“This is an issue of election law,” said Lisa A. Capatina, the chair of the canvassers board. Capatina and Toni Sellars, the Republicans on the board, voted against tabulating the ballots, while Democrats Richard Preuss and Edward Keelean voted in favor.

The canvassers ultimately tabled the decision on the advice of Becki Carmargo, assistant corporation counsel for Wayne County. They will reconvene on Friday afternoon. The state deadline for canvassing is Tuesday.

Preuss said he would love to hear from residents before making a decision.

“There seems to be a robust amount of people here at this meeting today that would like to have a chance to speak,” he said.

Those who spoke during public comment at Thursday’s board meeting were split. A number of self-identified Hamtramck residents said it would be wrong to disenfranchise those 37 voters, while others felt those ballots should no longer be considered after the chain of custody was broken.

Investigations into Hamtramck elections

The revelation is yet another blow to election confidence in a city that has been racked by scandal. Several members of the City Council are being investigated for alleged election crimes, and one person who was also under investigation won election to the council last week. There have been accusations of ballot stuffing, intimidation, fraud, and more, including felony charges against council members.

Meanwhile, Faraj confirmed she has been on paid leave since Monday, which she told Votebeat on Thursday during the meeting was “for her safety.” She did not expand on what that meant.

Even if the 37 ballots are eventually counted, the election isn’t over. The city also has 120 “cured” ballots left to include in the final totals, Greg Mahar, the director of Wayne County elections, told the canvassers. That’s a significant number for a city of around 28,000 residents; Detroit, in comparison, had only 72 for a city of nearly 650,000.

Cured ballots are absentee ballots that weren’t counted originally because either the signature on the envelope was missing or it did not match the signature on file. In these cases, the clerk’s office reaches out to the voter and gives them until the Friday after the election to correct it, so their ballot can be counted.

It’s unclear why there were so many cured ballots in Hamtramck. Mahar attributed it largely to the open-seat race for mayor, but Detroit — which also had an open mayoral race — did not see the same spike.

“It is a bit unusual,” he told the canvassers.

Correction, Nov. 14: An earlier version of this story misstated the title of Becki Carmargo. She is assistant corporation counsel for Wayne County.

Hayley Harding is a reporter for Votebeat based in Michigan. Contact Hayley at hharding@votebeat.org.