Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

As counties around Pennsylvania toiled to count ballots on election day — again under pressure to report results within hours of polls closing — one rural northeast county put to work its creative solution for conquering such a big job with a small election staff.

Very small: two people.

The demands of processing ballots from Pennsylvania’s different methods of voting have led some county election officials to say they actually run two separate elections every time. The 2019 law that greatly expanded who can vote by mail does not prescribe a system by which counties must count their ballots, so counties each have designed various processes and made different adjustments to accommodate one of the most consequential changes to the state’s elections in recent history.

Depending on the size of a county, its resources, and its county government politics, some approaches work better than others.

Columbia County, with fewer than 39,000 registered voters, realized it could only pull off its “two elections” more smoothly if the office got lots of extra help. Its election day operation is now based on robust cooperation from employees across the county government.

“One of [counties’] core responsibilities is elections, and we have to do them well,” said County Commissioner Chris Young, a Republican whose job also puts him on Columbia’s Board of Elections. “My philosophy was — and the other two commissioners obviously support it — was all hands on deck. We don’t segregate it and say ‘Oh this is only election’s responsibility.’”

“When we’re running elections, it involves everybody.”

County leaders’ spirit of cooperation extends out to county residents, too. By inviting people in to participate in their election decision-making and to see all aspects of the election process themselves, they say they’ve won the public’s faith. Voters in the county, which favored Donald Trump in 2020 by more than a 30% margin, voiced that trust themselves during election day interviews.

County leaders don’t know for sure if they can take credit, but they note that election conspiracy theories have not taken as strong of a hold here as they have in other parts of the state, such as nearby Lycoming County. There, election conspiracy theorists succeeded in pressuring county leaders to order a hand recount earlier this year of the 2020 presidential election.

“We haven’t had the anti-trust, it hasn’t been to the same level here as some places,” said Young, who has consistently pushed back against accusations of election fraud.

Whether Columbia’s “all hands on deck” election effort remains in place after this year remains to be seen, given a political shakeup caused by Tuesday’s results.

How Columbia runs its elections

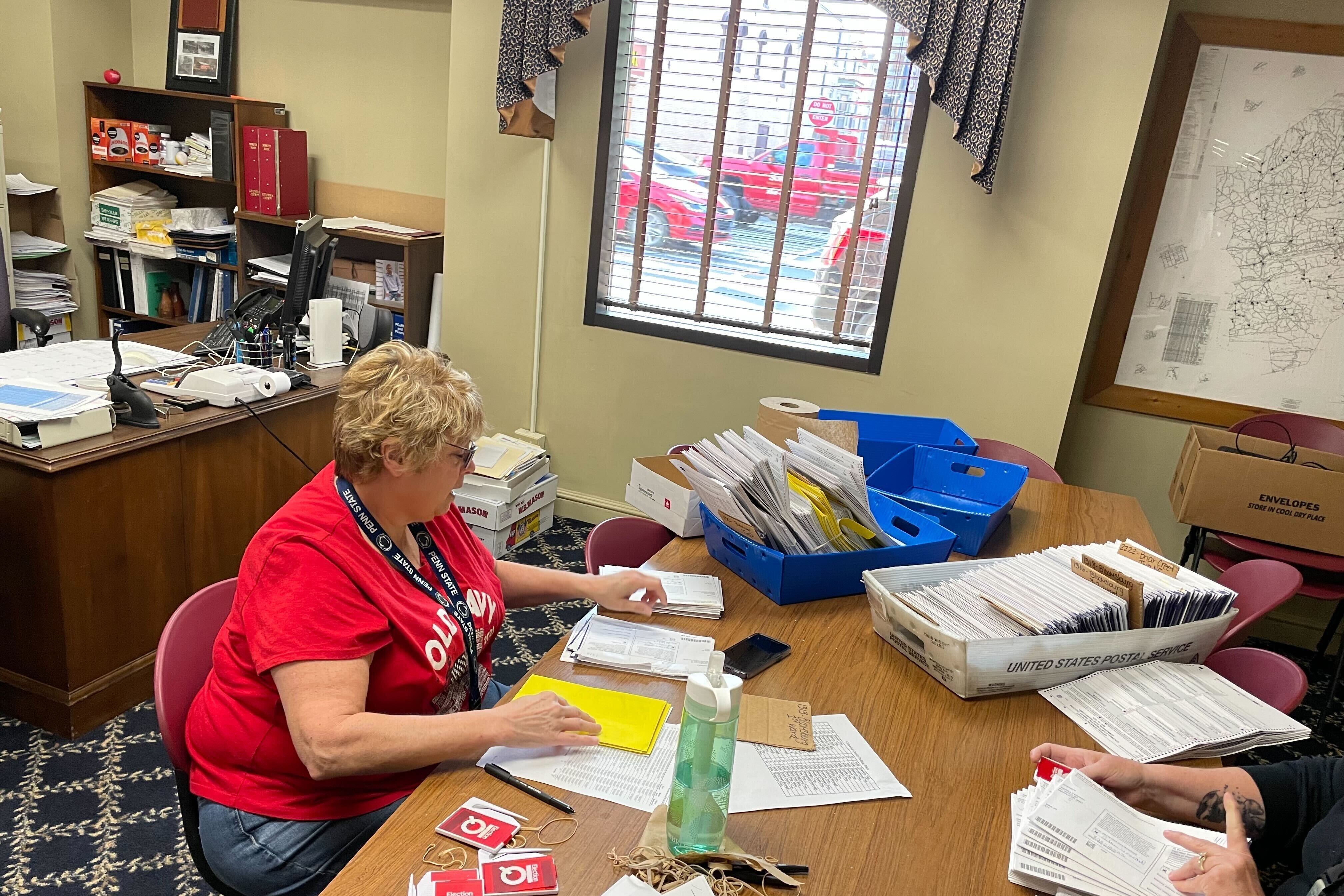

Throughout Tuesday, Columbia’s two-person election staff, Director Matthew Repasky and Assistant Voter Registration and Election Coordinator Thea Karas, were busy taking calls from poll workers and collecting mail ballots from voters returning them to the office.

That left them with no bandwidth for carrying out the county’s other election — the tallying of nearly 1,900 mail ballots. Columbia’s commissioners, who make up the board of elections, handed primary responsibility for that to an unlikely county employee from outside the elections office: the county’s human resources director, Marcie Strachko.

In 2020 when Strachko saw the elections department struggling to keep up with the influx of new mail ballot applications, she stepped up.

“When everything started, they were just so overwhelmed,” she said. “I just said, ‘I’ll take over.’ ”

Then, Strachko brought in reinforcements.

Estimating that one employee can open 400 envelopes in one day, Strachko assembles a team of employees from across the county government to assist her each election day.

An employee of the Treasurer’s Office organized ballots alphabetically ahead of election day to ensure counting went smoothly. County Chief Clerk Dave Witchey lent them the conference table in his office and helped upload results at the end of the night. Jeannie Lapinski, the county’s finance director, seamlessly sliced open mail ballots with a hand-held envelope opener while taking calls on speakerphone about the county’s finances.

Throughout the morning, four to six other employees filtered in and out of the office to process batches of ballots, also grabbing hand-held envelope slicers so they could open the outer and inner envelopes and unfold the ballots. By 10:15 a.m., all the ballots received ahead of election day were processed and ready to be scanned that night, alongside the 75 or so that would arrive over the course of Tuesday.

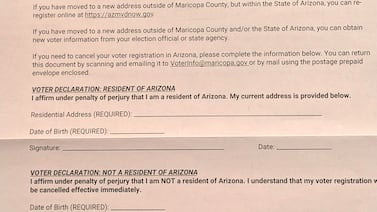

There are processing decisions these workers can make, and some that they can’t. Strachko and other employees know to automatically set aside mail ballots that have clearly disqualifying errors — if the voter failed to sign the envelope, say, or if the inner secrecy envelope is missing. But tougher questions — such as whether to count a ballot with a date written in the wrong spot on the return envelope — still get decided by Repasky.

For the most part though, Repasky said he stays out of the way of the mail ballot team because “they’re doing a great job.”

Many counties choose to have their director and deputy director split the in-person and mail-in election duties, leading teams to manage each.

That isn’t an option for Columbia, as Repasky and Karas were both busy running the in-person election Tuesday, despite the relatively low turnout that comes with a municipal primary.

Columbia is a majority Republican county, with two Republican commissioners who could consistently outvote the Democrat if they chose. But Witchey, the county clerk, and Strachko, the human resources director, agreed the commissioners’ commitment to bipartisan, collaborative leadership created a positive environment where employees work together.

“We’re very fortunate, the county works as a team,” Strachko said. “Not to say we always agree, we don’t, but we’re very fortunate.”

Witchey said it is this culture that has led to the success of their elections operation. And the openness between staff is something they extend to the community as well.

Public perception

Columbia has not been entirely immune to election conspiracy theories.

Last August, a local venue in Bloomsburg hosted a meeting of conspiracy theorists like Toni Shuppe of Audit the Vote PA and Catherine Engelbrecht of True the Vote, conservative groups that falsely claim the 2020 election was fraudulent.

A local group, We the People of Columbia PA, was successful in filing petitions to have ballots in the November midterms recounted in some precincts.

But Audit the Vote did not organize a door-to-door canvassing effort in Columbia as they did in counties where support was greater, like Washington, Lancaster and Butler. The county also did not face pressure to hand count ballots — a preference of election skeptics who don’t trust vote-counting machines — like nearby Lycoming, or York County to the south.

“I always tell people, if you want to challenge us, come in and see (our election process),” Witchey said.

While some counties only allow party members or credentialed media in to view their operation, Columbia is willing to give a behind-the-scenes look to anyone who has questions.

When a woman interested in the school board races stopped by shortly after polls closed Tuesday night to ask if results were in, Witchey said they were not, but added, “You’re more than welcome to stay if you want to see the process.”

Voters and party officials who spoke with Votebeat and Spotlight PA said they appreciated the county’s transparency and had faith in their process.

Tom Treadway, a Republican from the county’s seat, Bloomsburg, said he hadn’t heard any complaints about the county’s elections in the 20 years he’s lived there.

Michael Conner, a Democrat who dropped off his mail ballot at the county office, was intrigued by the county’s offer of viewing the process and said he might take them up on it.

Janine Penman, secretary of the Columbia County GOP, said the office does a “tremendous job.”

“I always get the answers for the questions I ask and there is always transparency,” she said. “They do invite anybody in, they say, ‘You can come in and watch.’”

The county also sought community buy-in when selecting its new voting machines in 2019, allowing citizens to vote on which one they preferred, Young said.

When asked if cultivating trust was only possible because of Columbia County’s small size, Young said larger counties could achieve the same effect.

“Maybe it’s not to the level as it is here, but they can always make sure you are giving as much access and are being as transparent as you can possibly be.”

What’s next for Columbia

There’s no guarantee that Columbia County’s current approach to elections won’t change.

How elections are run is up to the county’s board of commissioners, and there is a strong possibility there will be an entirely new board come January.

Young, a Republican, did not run for reelection this year, and the other Republican commissioner, Rich Ridgway, lost his reelection bid Tuesday.

On the Democratic side, incumbent David Kovach secured his spot on the November ballot, as did another candidate, Patricia Lawton, who received more votes than Kovach. Only one is expected to win one of the three open seats in November, due to the county’s heavily Republican voting trends.

Some county employees were nervous Tuesday night about the prospect of entirely new leadership after so many years, with one even mentioning they had already applied for a new job.

Witchey said they weren’t necessarily worried about any particular candidate or thing a candidate had said, but rather just about the “prospect of something new.”

Witchey said he’ll show whoever is on the Board of Elections after the November election how the system currently works and explain the county government’s collaborative culture, but ultimately it will be up to the commissioners to decide how to run things.

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org