Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Texas’ free newsletter here.

This story was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

EL PASO, Texas — When Texas first proposed redrawing its congressional map earlier this summer, critics decried it as a political power grab to appease the president, while state leaders claimed it was necessary after the Department of Justice raised concerns about some majority non-white districts.

But now that the map is in federal court, the two sides have swapped stances.

The state now claims it acted for purely partisan gain, which the U.S. Supreme Court has said is lawful, while a group of individuals and advocacy organizations argue the Department of Justice’s involvement reveals an unconstitutional racial motivation.

These plaintiff groups, who are also suing over the 2021 maps, have asked a district court in El Paso to block the maps from being used in the 2026 election. The nine-day hearing kicked off Wednesday, with state Rep. Joe Moody, a Democrat from El Paso, testifying that his Republican colleagues absolutely had partisan goals.

“But how you get there matters,” he said. And in this unusual mid-decade redistricting, the Legislature’s path to gain more Republican seats in Congress “depressed the ability of Black and Hispanic voters to elect their candidates of choice,” he said.

Moody testified alongside state Sen. Carol Alvarado, a Houston Democrat who spoke about the impact of the changes on her city’s historically Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. Other state legislators are expected to testify for the plaintiffs’ side over the next four days, before the state presents its witnesses.

Justice Department letter is a point of contention

The plaintiffs claim that state lawmakers intentionally diluted the voting power of Black and Hispanic Texans by breaking up majority non-white districts at the urging of the Department of Justice.

This letter from the DOJ, which came after President Donald Trump began pressuring Texas to redraw its congressional map, has become a major conflict point. In the letter, Assistant Attorney General Harmeet Dhillon directed Texas to redraw four “coalition districts,” in which multiple racial groups together form a majority.

Dhillon cited a 2024 ruling from the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals that said an individual racial or ethnic group must make up a majority of a district to bring a voting rights lawsuit. The ruling did not direct states to redraw their existing districts where multiple racial groups combine to make up a majority. In fact, to do so would potentially violate the Constitution, several legal experts told the Legislature at various points during the process.

At Wednesday’s hearing, Steven Loomis, an assistant attorney general representing the state, rejected the letter as irrelevant, noting that Dhillon is not a lawmaker, that she didn’t play a role in drawing the maps, and that her claims “don’t bind the Texas Legislature.”

But Gov. Greg Abbott said in several television interviews that this letter, and the court ruling, was what pushed him to add redistricting to the special session agenda — interviews that the plaintiffs’ lawyers played repeatedly at the hearing. Moody testified that it was his understanding that the letter from the DOJ was “what set the special session,” as it gave state leaders the “checkbox” they needed to proceed.

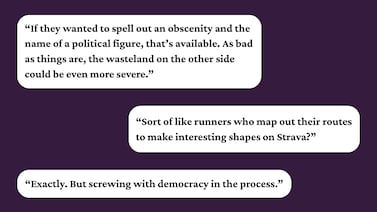

The state maintains that it was motivated entirely by pressure from Trump’s team to add more Republican seats, and that race wasn’t a factor. Loomis pointed to statements from Democratic lawmakers who called the process “pure politics” and a “fascist power grab” to show they agree this was motivated by GOP goals.

The plaintiffs are also arguing that the state racially gerrymandered, meaning race was the predominant factor in how it drew some of the districts. They pointed to several districts that are now just barely over 50% of one race, claiming the state moved some people into certain districts based on their race to meet a performative threshold.

These districts were drawn as “window dressing,” to allow lawmakers to claim they were helping voters of color while actually diminishing their ability to elect their candidate of choice, Moody said.

Who drew the maps?

Throughout the summer, Republicans lawmakers again and again claimed that the entire process was race-blind, hoping to sidestep any concerns about unconstitutionally considering race in the redraw.

But the plaintiffs’ lawyers questioned the validity of those claims at Wednesday’s hearing, and homed in on a central question that’s hung over the entire process: Who drew Texas’ new congressional map? And did they consider race while doing so?

Adam Kincaid, the executive director of the National Republican Redistricting Trust, drew Texas’ 2021 maps. Many assumed he would draw the 2025 map as well, but early on, Republican leaders sidestepped questions about his role in the process.

Rep. Todd Hunter, the Corpus Christi Republican who carried the House version of the map, told colleagues he didn’t know whether Kincaid had drawn the map, while committee chair Rep. Cody Vasut said he didn’t know who Kincaid was.

Senate redistricting committee chair Sen. Phil King, a Weatherford Republican, faced blowback when he revealed toward the end of the process that he and Kincaid had chatted three times in recent months.

“We visited a few minutes,” King told lawmakers. “I specifically told him: ‘Don’t tell me anything you’re doing with regard to map drawing. Don’t tell me about the details of any map if you’re involved in it.’”

Moody and Alvarado both expressed frustration over not knowing who was drawing the map or what data they consulted in doing so. In the 2021 redistricting process, the state demographer and the attorney general’s office were on hand at all the hearings to answer questions, but no similar services were offered this time, they said.

Nina Perales, a lawyer with the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund who is representing some of the plaintiffs, said it was a “legislative shell game” to figure out who had drawn the map.

These questions may soon be answered: The state has said it will call Kincaid as a witness next week.