A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

Good morning,

It turns out that the much-publicized spate of new state laws banning private grants for elections may have left a route open for private money after all. It flows through law enforcement.

Conservative nonprofit True the Vote has announced it will partner with conservative sheriffs’ groups to fuel investigations into 2020 voter fraud allegations and increase surveillance of voting.

The announcement comes as some sheriffs have embarked on high-profile investigations into the 2020 election that echo debunked allegations of voter fraud, prompting worries that the sheriffs are overstepping their authority and working with activists intent on discrediting the election results.

“A little ironic, don’t you think?” said Neal Kelley, the former registrar of voters in Orange County, Calif. Kelley, who is also a former police officer, now chairs a committee supported by several outside nonprofits that is meant to build stronger relationships between election officials and law enforcement.

“We’ll fund law enforcement with private grants, but you guys [in election offices] can’t touch it, which makes no sense to me,” he said, pointing out that law enforcement at the polls is a sensitive issue because of the potential for voter intimidation.

Obviously, grants to sheriffs to pay for investigations into suspected voter fraud aren’t necessarily covered by laws banning grants for the purposes of election administration. But the public’s discomfort with the potential of private money to influence elections, and the perception that private dollars could sway public officials, could logically extend to grants fueling election-related investigations, too.

“If you’re truly motivated by concerns of partisan actors kind of getting in the space of election integrity, presumably this would cause the same concerns,” said Sophia Lin Lakin, the deputy director of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project. “I don’t see a distinction.”

As we’ve written before, election officials across the country accepted millions of dollars in private grants from the nonprofit Center for Tech and Civic Life and other groups to pay pandemic-driven election administration costs in 2020. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, funded the lion’s share of the grants (though former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger awarded millions of dollars via a separate program).

The CTCL grants didn’t have conditions attached to them. The nonprofits awarding the money stressed that Zuckerberg had no direct role in distributing the cash, no election official who applied was turned down, and every jurisdiction got the amount they requested.

Election officials themselves were quick to acknowledge that paying election costs via private grants isn’t ideal, but said the failure of state and federal governments to allocate enough dollars left them few options to deal with 2020’s pandemic-related costs.

Nonetheless, the grants set off a conspiracy theory-fueled backlash, with former President Donald Trump and his allies blaming them for his loss and alleging, without evidence, that the money was earmarked to boost Democratic turnout. That backlash prompted the new laws

Speakers at a panel on elections this week hosted by the America First Policy Institute, a think tank with close ties to Trump, repeatedly went back to the dangers of the CTCL grants, which panelists referred to as “Zuckbucks” or “Zuckerbucks,” and private funding.

“Think of the number of legislatures that after Zuckbucks was exposed that went out and actually passed proactive legislation that said we don’t want private dollars infected in our election systems,” said Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, a Republican who in 2020 blocked Louisiana election officials from accepting such grants. Landry’s office didn’t respond to a question from Votebeat about whether Louisiana sheriffs could legally accept the newly announced grants.

Meanwhile, election officials are still struggling to assess what, exactly, is prohibited by the new laws banning private resources. The ACLU’s Lakin and others said they’re concerned about the statutes and what’s restricted under them.

For example, in Virginia, state legislators passed a new law this year that says election officials “shall not solicit, accept, use, or dispose of any money, grants, property, or services.” The sweeping language has left local registrars puzzling over whether seemingly benign longtime partnerships and donations are still allowed, said Brenda Cabrera, the director of elections/general registrar for the city of Fairfax and the current president of the Voter Registrars Association of Virginia.

“As time goes on, we’re discovering more and more things that probably fall into the category of, ‘You can’t do that any more,’” she said, giving examples including volunteers from local Scouting groups offering to help transport supplies or put up and remove signage at polling sites, or donations of pizza or coffee for election workers.

“You’re talking about people who make a career in adhering to laws,” she said, referring to local election officials. “They want to be compliant. They’re very concerned about that. But the letter of this law seems to be far more restrictive than is really logical.”

Chris Piper, the former state elections commissioner for Virginia, said he and the state’s registrars “expressed concern” over some of the language in the new law before it passed. Piper is now chief operating officer of The Elections Group, an elections consulting firm that provides many services and resources to election officials pro bono.

Banning private money in elections isn’t a bad motivation, he said, but has to be balanced with providing proper funding and “the language needs to be carefully crafted so we don’t end up with some of these unintended consequences where election officials actually get no support. That’s not what anybody wants.”

That brings us back to the new initiative from True the Vote, the conservative nonprofit behind the film “2000 Mules,” which claims thousands of so-called “ballot harvesters,” whom the film refers to as “mules,” illegally deposited ballots into drop boxes during the November 2020 election. The film’s allegations, which rely heavily on inconclusive cell phone location data, have been widely debunked.

According to Reuters, True the Vote said the coalition with the sheriffs’ groups is meant to “encourage sheriffs to pursue election-fraud claims,” and also plans to “provide sheriffs with ‘artificial intelligence’ software to assist in analyzing the video they collect,” as well as setting up hotlines to alert sheriffs to suspicious activity related to elections. The organization has said it has raised $100,000 for its sheriffs’ initiatives so far, and hopes to raise $1 million.

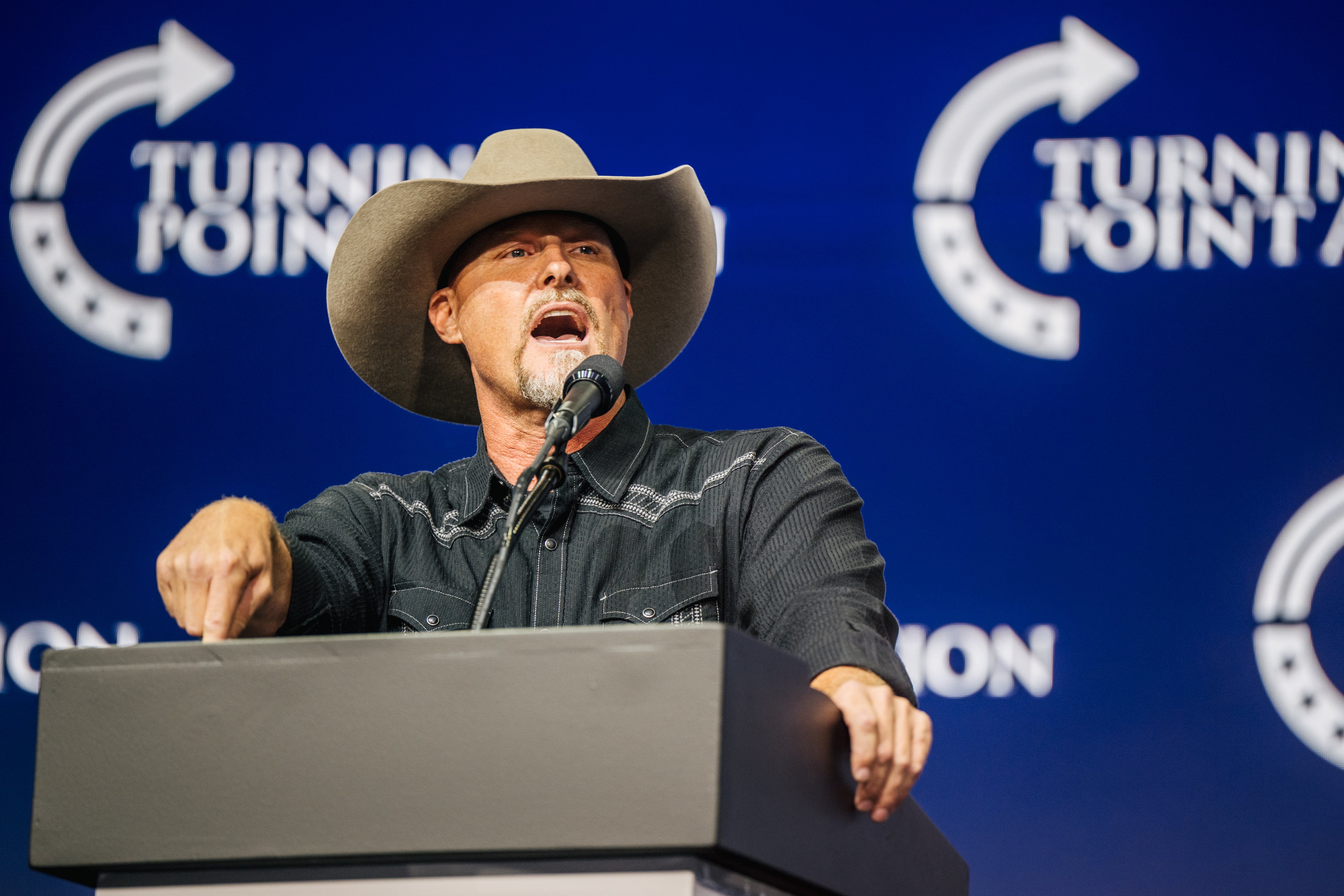

One of the groups, Protect America Now, is run by Sheriff Mark Lamb of Pinal County, Arizona. The New York Times reported that when discussing the True the Vote partnership at a recent Arizona rally, Lamb said, “We will not let happen what happened in 2020.”

Sam Oliker-Friedland, executive director of the Institute for Responsive Government, which partners with CTCL on the Election Infrastructure Initiative, pointed out that local sheriffs are typically better funded than local election administrators. In addition, he said, election administration is “one of the most transparent government functions that we have,” and law enforcement is not.

“With private funding of law enforcement you’re really going to be able to pay to have your neighbor investigated in a way that your neighbor can never dig into or learn about, and I think that is in many ways more dangerous,” he said.

Back Then

In 1981, the Republican National Committee coordinated an effort to have armed, off-duty police at polling locations in New Jersey during a gubernatorial election, deterring voters, including many Black and Latino voters. The Democratic National Committee sued, alleging racially discriminatory voter suppression. As a result, the RNC for decades was subject to a consent decree limiting its poll watching efforts; it was lifted in 2018.

Corrections: Last week’s newsletter mistakenly gave incorrect information about how Madison was chosen as the site of this summer’s conference of the National Association of State Election Directors. Madison was chosen by a vote of the NASED executive board from a list of places where elections are not overseen by a secretary of state or lieutenant governor.

In our July 16 newsletter, Jessica Huseman wrote that she would be speaking on a panel at the NASED conference that week. Her panel was organized by the Sector Coordinating Council, in conjunction with the NASED conference.

New From Votebeat

- Michigan is one of a handful of states that prints Republican and Democratic candidates on the same primary ballot. But if voters select candidates across party lines during next week’s election, their ballot can’t be accepted — a quirk that confuses voters and could disenfranchise some using mail ballots, Oralandar Brand-Williams reported in her first article for Votebeat Michigan.

- Leading up to Michigan’s first major election since the frenzy of 2020 election conspiracy theories, election officials are again holding public events to demonstrate their regular testing of election systems — and again are finding little interest in seeing the technology and the process up close, Brand-Williams reports.

In Other Voting News

- A new investigation by Georgia Public Broadcasting and NPR found that more than half the Georgia voters who used drop boxes in the 2020 general election live in one of four metro Atlanta counties where more than half the voters are of color, and that under the state’s new election law, the number of drop boxes in those four counties went from 107 to 25. A quarter of the state’s voters saw their travel time to a drop box increase, the team’s data analysis found.

- Conservatives in Georgia are challenging thousands of voter registrations under a new state election law that allows anyone to challenge someone’s eligibility, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reports. Election officials so far have upheld a relatively small number of the challenges, and say existing procedures are enough to ensure voter rolls are up-to-date.

- New York City is appealing a Staten Island judge’s decision to strike down a law giving certain noncitizens voting rights in local elections, reports Gothamist. The law would grant voting rights to foreign-born residents who are legally working and living in the city. Opponents argue that the bill violates the state Constitution.

- A Kansas appeals court ruled that Secretary of State Scott Schwab violated the Kansas Open Records Act by altering a computer system to disable its ability to produce public records. The appeal is a follow-up to a previous lawsuit in which Secretary Schwab was ordered to turn over provisional ballot reports after Loud Light, a nonprofit, filed a request for the documents.

- Republicans are suing over new voting laws in Delaware, reports Delaware Public Media. The bills, which passed despite heavy Republican resistance, allow Delaware residents to register on Election Day and to vote by mail.

- The portrait of Latina voting rights activist Adelina Otero-Warren will be stamped onto a U.S quarter this summer. Otero-Warren, of New Mexico, was the first Latina to run for Congress, in 1921, and advocated for Spanish-language classes in the U.S., as well as suffrage for women.

- Pennsylvania Republicans are again challenging a mail-in voting law that helped they pass. Act 77 enabled no-excuse mail-in voting in the state. Republican lawmakers are attempting to get the law thrown out on the grounds that a previous ruling allowing undated ballots to be counted invalidates a provision of the law, and thus nullifies the whole statute

- Some Republican-led counties are refusing to certify election results, something experts worry could become a way to disrupt democracy and sow doubt about future elections.

- Staff departures have forced the temporary closure of Florida’s Monroe County Supervisor of Elections Office, reports Keys Weekly. The office lost three employees and has yet to find replacements, forcing it to close until early voting begins in early August.

- Ten Floridians with previous felony convictions are being charged with voter fraud after a government official helped them register. ProPublica reports all were charged with fraud on the grounds that they were ineligible to vote due to failing to pay fines and fees connected to their convictions. Critics of the prosecution say that the official who helped them register did not tell the felons of the required fees, and the charges are an attempt to disenfranchise voters.

Good News Of the Week

By Christian McCann, Votebeat intern

Amid all the news of threats against election officials and staffing shortages, you don’t often hear an election official express the sentiment shared by the clerk of Park County, Wyoming: “I love the job. I like helping where I can help … I just like working with people,” said Colleen Renner. Only part of Renner’s job involves running elections, but this year it’s taking up much of her time. “It was a challenge at first in 2015, but I feel I’ve come a long ways and have improved a lot of things here.”

Carrie Levine is Votebeat’s story editor and is based in Washington, D.C. Contact Carrie at clevine@votebeat.org.