Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

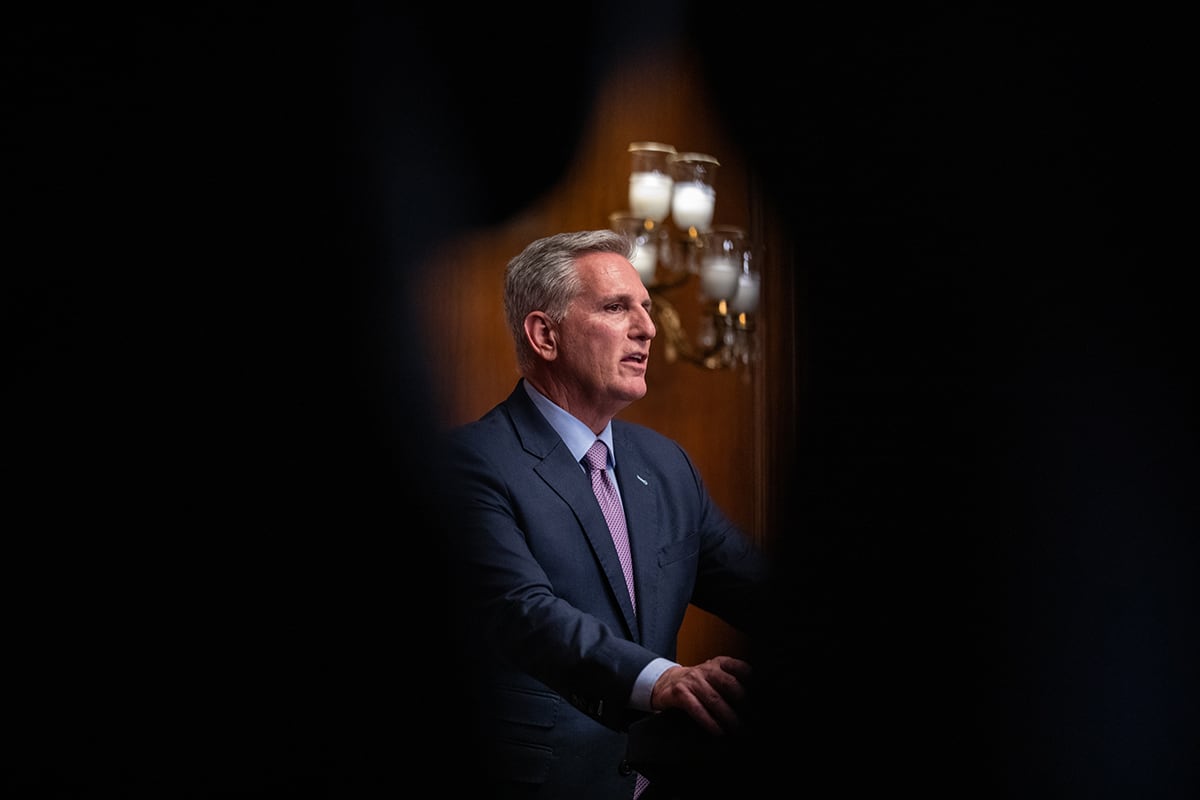

Congress managed to narrowly avert a shutdown of the federal government this month, passing a 45-day extension of funding to buy itself time to come to a budget deal. Then, in a historic move members of the U.S. House of Representatives ousted House Speaker Kevin McCarthy.

In doing so, lawmakers all but guaranteed they’ll spend much of that 45 days attempting to figure out who is in charge — not coming to a spending deal. So yes, the prospect of a shutdown still looms.

Federal government shutdowns affect almost every corner of American life. That, of course, includes elections, though the effects are less likely to produce immediate headlines than failing to pay the military. It may seem unnecessary to worry about the effect on federal elections that are still more than a year away, but “most Americans don’t realize that election officials are planning for 2024 right now,” said Kim Wyman, who until recently was senior security advisor for the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and is also a former Washington secretary of state.

For an example of why it matters to elections, let’s look to the last time Congress went down this road.

In 2018, Pennsylvania required its counties to purchase new voting machines that were certified by both the state and the federal government, preferably in time for the 2019 general election, but certainly before the 2020 primaries.

Then, the federal government began lurching towards a shutdown. And one of the voting systems Pennsylvania wanted available for counties to purchase was still mired in the federal certification process, former Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar recalled.

“We knew we needed to have this done so that counties could move forward in the beginning of 2019,” she said, and she and her staff began making daily calls to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, trying to move the process forward. The voting system got preliminary approval, Boockvar said, days before the shutdown — the longest in American history — began.

Well, here we are again. And if Congress somehow manages to avoid a shutdown in November, it will have to approve federal spending again when the fiscal year ends, weeks before the 2024 presidential election. Given the events that played out in the U.S. House this week, don’t bet against chaos.

Since the federal government declared elections to be critical infrastructure in 2017, the partnership between local, state, and federal officials has gotten even tighter. Election officials, already struggling with unprecedented threats and challenges in the leadup to the 2024 presidential elections, would be contending with yet another hurdle if those federal officials are sidelined by an appropriations breakdown.

Foreign adversaries, especially Russia, will certainly be attempting to interfere with the elections, said Michael Chertoff, who was the secretary of homeland security under former President George W. Bush, who stressed the Russian interest in weakening American support for Ukraine.

Chertoff, speaking at a briefing by the National Task Force on Election Crises on Wednesday, said it’s important that federal officials help state and local election officials by advising on cybersecurity and physical security, and “first of all providing intelligence about where disinformation is coming from, what it might be like, what kinds of disruptive efforts there might be.”

In the case of a shutdown, Chertoff said he hoped that federal employees monitoring and providing advice on election threats would be declared essential, and said agencies should move to pay out any grants as soon as possible to hedge against the likelihood of a disruption.

One of CISA’s critical roles is to offer election officials assessments of their workspaces’ physical security and cybersecurity. In the days leading up to last week’s deadline, the agency said it would have to suspend such assessments entirely if government funding were to lapse. Election officials began to lobby.

Neal Kelley, a former election official from California who now chairs the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections, a coalition, sent Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas a letter raising concerns about the service interruption. Arizona Secretary of State Adrian Fontes, a Democrat, was concerned enough, he told Votebeat’s Jen Fifield, to travel to Washington, D.C. to try to convince federal officials that election security employees should be permitted to work during any shutdown. Fontes’ spokesman confirmed he met with CISA “regarding potential disruptions to federal election support and funding for Arizona.”

The worry isn’t about “a significant immediate impact,” said Rachel Orey, senior associate director at the Bipartisan Policy Center Elections Project. “Our concern is over time.”

For example, Orey points out, CISA is already backlogged on security assessments for local election offices. If CISA’s backlog grows due to a shutdown, Orey said, it’s likely that local offices “won’t be able to implement physical improvements going into the high-stakes, high-turnout election next year.” Election officials also might need to contact the U.S. Election Assistance Commission about how to properly use federal grant money, she said.

For her part, Wyman said she hopes the possibility of a federal government shutdown won’t slow CISA’s plans to hire election security specialists around the country.

But either way, it is yet another contingency that election officials must take into account.

“What impact does that have on their election planning? What’s their incident planning if the federal government does shut down before the general election in 2024, and exacerbated by the fact that we’ve had an exodus of election officials that are seasoned and have run a presidential election before?” Wyman asked.

Back Then

Herbert Hoover and Alfred E. Smith faced off in the 1926 presidential election that was ultimately won (of course) by Hoover. It was a far more staid affair than today’s campaigns: Hoover only gave seven speeches, none of which mentioned Smith by name. Still, people got pretty excited. According to wire coverage from Election Day that year: “The first death due to the election was reported from Jamaica, Long Island, where a voter dropped dead in a voting booth. The voter was Charles Leutersack, 44, of Queens Village, who was stricken with a heart attack as he was about to cast his ballot. An ambulance was summoned but the man was pronounced dead, probably from over excitement, by the ambulance physician.”

New From Votebeat

From Votebeat Pennsylvania: Pa. House advances bill to move 2024 primary while rejecting voter ID, mail ballot changes

From Votebeat Pennsylvania: Pa. Republicans say Gov. Shapiro can’t just adopt automatic voter registration. Here’s what the law says.

In Other Voting News

- In closely watched litigation with the potential to reshape government efforts to address inaccurate election information online, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit is barring the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and top officials from any actions that “coerce or significantly encourage” tech companies to remove or reduce the spread of posts, the Washington Post reported. The government has insisted it didn’t violate First Amendment protections, and has asked the Supreme Court to intervene.

- Arizona Secretary of State Adrian Fontes has officially submitted his draft of the state’s Elections Procedures Manual to Gov. Katie Hobbs and Attorney General Kris Mayes for final approval. Read more about the EPM from Votebeat’s Jen Fifield.

- A federal judge ruled a defamation lawsuit from a man who alleges he was defamed by the film “2000 Mules” can continue to trial, though he dismissed some claims, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported.

- Virginia election officials acknowledged mistakenly canceling the voter registration of an unknown number of people who had been convicted of a felony, had their voting rights restored, then had probation violations, and were working to reinstate them on the voter rolls, VPM reported.

- A state Senate committee in Kansas conducted a two-day meeting featuring out-of-state activists with virtually no expertise in elections who furthered vote fraud misinformation and conspiracy theories, to the exclusion of local election officials and reputable experts, and at a cost of $6,600 to taxpayers, the Kansas City Star reported.

- Arizona election officials are continuing to raise the alarm about a new state law lowering the threshold for recounts in close elections, saying it could delay election results, the Washington Post reported. When the law passed last year, Votebeat reported it could add to election costs and delay final results.

Carrie Levine is Votebeat’s story editor and is based in Washington, D.C. She edits and frequently writes Votebeat’s national newsletter.Contact Carrie at clevine@votebeat.org.