Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter.

Strap in, because this newsletter is about government procurement.

Have you read a “request for proposal?” Or, as those in the know call them, an RFP? Let me introduce you to this thrilling library of them, housed by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. They are the very long things counties write soliciting proposals from companies interested in selling a voting system (or any expensive thing) to the county. They lay out the county’s requirements for the system — technical specifications, wishes, dreams — and offer background on the office making the purchase and how the bidding process will work.

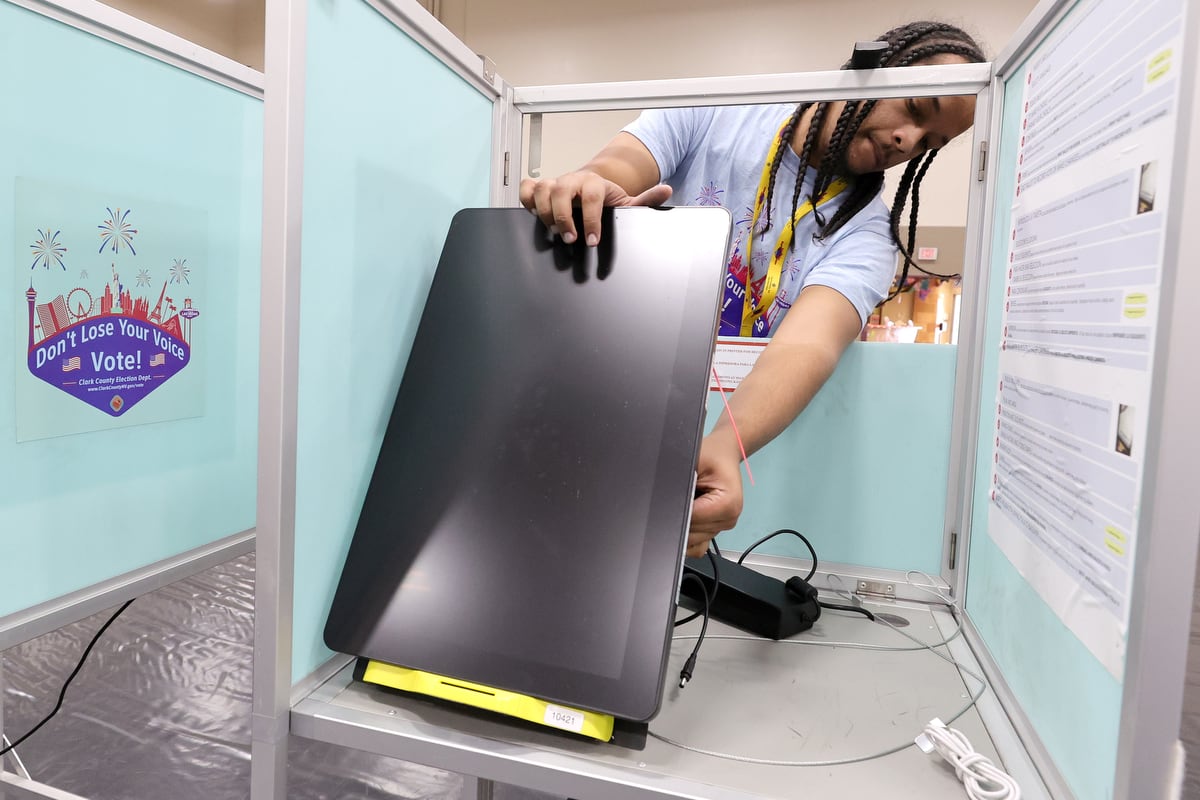

After the RFP is published, bidding can take several more months, a contract is issued, there is perhaps litigation over the contract, and at some point — maybe not until the litigation is resolved but certainly not before the contract has been awarded — the machines get built to the specifications required. They are delivered, supply chain willing, months after that. In other words, it can frequently take more than a year between a community deciding it needs new voting machines and the arrival of said machines.

I walk you through this mind-numbing process because (I don’t know if you have noticed) state legislatures are up and running. And if they’ve proven one thing over and over and over again, it’s that they love to write bills about what voting machines everyone is required to buy without actually considering practical realities, such as a timeline that is close to an edict in county government and changes for no man or bill.

Consider some truly bananas recent reporting from Texas reporter Natalia Contreras. In short (though, please read the whole thing, it’s very good), Texas legislators in 2021 passed a bill that requires the entire state to purchase fictional machines by 2026. The new law was created to solve a fictional problem — that somehow poll workers were changing votes as the totals are in transport, which they cannot and do not. So lawmakers set requirements for voting machines that can’t be met by currently existing equipment. Natalia does a better job explaining the technical points than I will here, but take my word for it: These machines do not exist. And even if they did, the bill is roughly pegged to cost more than $100,000,000. Eight zeroes. E-i-g-h-t.

Meanwhile, in Michigan, voters approved a series of expansive voting reforms that will cost millions of dollars. Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson will ask for up to $12 million to purchase and secure drop boxes, which don’t get manufactured in a hurry. If the state Legislature there drags its feet, the state may not have them in time for 2024.

History is replete with other such examples. You’ll recall my thoughts on HR 1, among them: That legislators were trying to require machines pegged to Voluntary Voting System Guidelines 2.0, a set of voting machines standards and specifications, by 2024 when those machines would not even exist until 2025. Or the Illinois Automatic Voter Registration system, which required a wildly fast timeline that was obviously not possible, and as a result, the system has been plagued with problems since.

I don’t think legislators have learned from their mistakes. They often don’t. Instead, I anticipate that very many legislators will write bills requiring the full deployment of brand-new voting machines, scanners, tabulators or whatever else while ignoring the realities of the market.

I’m repeating myself here, but machines pegged to the VVSG 2.0 won’t be available for purchase until 2025. And, again, the process of purchasing them after they’ve been invented takes multiple months. Once those machines arrive at the county, it will take several months more to distribute them, train staff and poll workers how to use them, and mount the necessary voter education campaigns so that the public is prepared to cast ballots on them.

It is a lot of work. It is a lot of time. And laws that demand fictitious machines don’t make the clock spin faster. Instead, the laws have to be repealed, amended, or argued about in court. And who has time for that, honestly? Election administrators certainly don’t.

Back Then

Among my favorite fact about elections is that there was no requirement to have a digital, statewide voter roll until the Help America Vote Act of 2002, which required the “establishment of a centralized, interactive, statewide voter registration list linked to relevant agencies and all polling sites.” 2002 was a fascinating year — Nickelback’s “How You Remind Me,” for example, was the Billboard song of the year. It was not, however, a time when the internet was particularly user-friendly. States were required to have these voter rolls in place by 2005, but — see where I’m going with this — they were mostly incomplete across the country until around 2010. It turns out, making a huge government database from stacks of paper stored in hundreds of places isn’t that easy.

New From Votebeat

From Votebeat Arizona: How an Arizona official is making Cochise County a “laboratory” for election skepticism

From Votebeat Michigan: New estimate says $45 million for early in-person voting and new drop boxes for Michigan

From Votebeat Pennsylvania: Commonwealth Court rejects Senate Republicans’ attempt to force release of voter information

From Votebeat Texas: Overlooked provision of SB1 requires election equipment that doesn’t exist, at a cost of $100 million

In Other Voting News

- Lawyers for Dominion Voting Systems say Fox News has so far failed to turn over evidence in a high-profile defamation case, NBC News reported. The trial is set to begin later this year.

- Local officials are asking Tarrant County’s commissioner court to create an election integrity unit that would investigate potential cases of fraud and election practices, the Dallas Morning News reported.

- Pennsylvania Supreme Court justices agree undated or wrongly dated mail ballots cannot be counted, but offered no clear guidance on how counties should determine whether a ballot has been wrongly dated, a situation likely to create a patchwork of policies in different counties, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported.

- Black Lives Matter volunteers who brought food and water to early voters on long lines in Georgia during the 2020 election broke no laws, state election officials found, dismissing a complaint and referring the woman who filed it for potential charges for bringing a gun into a polling place, Georgia Public Broadcasting reported.

- Georgia state election officials don’t recommend a takeover of Fulton County’s elections, saying the county has improved its performance since the beginning of a prolonged review, but said future reviews need to be handled differently and the state must create a uniform process for the assessments, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported.

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org.