Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

Poll workers in Maricopa and Pinal counties will do an on-site count of how many mail ballots are dropped off at their voting locations on election day, but there’s debate among election officials and lawmakers over whether a new law requires them to do it at the polling place.

The language in the law had been interpreted differently across counties, according to the Secretary of State’s Office. Pinal election officials, for example, initially told Votebeat that they planned to keep counting the number of dropped-off mail ballots at their central counting facility, rather than at voting locations, because they believe that to be a more accurate, efficient, and secure process.

But after Votebeat asked state lawmakers and the Arizona Association of Counties about the differing interpretations, they stepped in to clarify the law’s intent. State Rep. Alex Kolodin, who led his party’s negotiations on the new law, and state Sen. Wendy Rogers, both Republicans, wrote to county election officials on April 4 explaining that the intent of the law was to require them to manually count the ballots — the number of ballot envelopes, that is, not the actual votes — at each voting location, before the ballots are transported to a central counting facility.

“We respectfully request, no later than April 18, 2024, written confirmation from each of your offices that you intend to implement the change,” Kolodin and Rogers wrote to counties.

The Arizona Association of Counties also wrote to counties saying the same thing about the counting location.

Pinal County has now changed its plans and will be counting the ballots at voting locations, according to Recorder Dana Lewis.

Still, not everyone believes they are required to.

The debate highlights how unclear changes in election law can be for election officials, especially when there are multiple changes at once, and they challenge longstanding practices. Meanwhile, politically fraught changes to ballot handling processes are forcing officials to confront new sources of human error that could undermine faith in elections.

What, exactly, does the law say?

The language about counting ballots is part of a law enacted in February to fix the state’s election calendar.

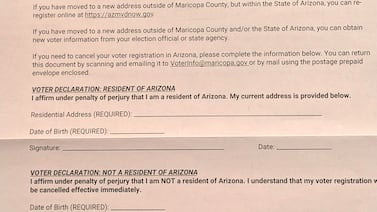

It says: “the county recorder or other officer in charge of elections shall count the number of early ballots that are returned at voting locations on election day.”

The provision was intended to ensure proper tracking of ballots that are dropped off at polling places, according to Kolodin, the GOP lawmaker.

Election law attorney Jim Barton said the provision does not specify the location where the counting has to happen. And Democratic state Sen. Priya Sundareshan, who helped lead the negotiations on the new law for her party, said she and other Senate Democrats did not read the language as naming a specific place for the counting, either.

“I think it is open to interpretation, and I don’t think the intent of the Legislature was unanimous in the Kolodin interpretation,” she said.

Most small counties told Votebeat they are already doing an on-site count of how many mail ballots they get at voting locations, which is manageable for them because there aren’t that many. But in large counties, and especially Maricopa County where hundreds or thousands of mail ballots are dropped off at each location, election officials worry that counting them on site will lead to inaccuracies, and add to the burden on tired poll workers at the end of a long day.

Maricopa County typically waits to count the exact number of ballots until it can use a high-speed machine at Runbeck Election Services, a private contractor that prints, receives, and scans mail ballots for the county. Elections Director Scott Jarrett said he wants the count to be as accurate as possible, in part because any errors could be misinterpreted.

“We want to set expectations that hand-counting is done by humans, and humans are imperfect,” said county elections spokesperson Jennifer Liewer. “You are never going to have an exact count.”

Maricopa County’s poll workers tried the on-site count for the first time during March’s presidential preference election, when sites received as many as 1,900 dropped-off mail ballots, and the tallies were inaccurate. For November’s election, the county expects 350,000 of these ballots to be dropped off across about 235 voting locations.

Jarrett is considering hiring additional staff, trained specifically for this task, so tired poll workers will not need to do it. But Jarrett warned that, either way, the new task will delay reporting of results on election night.

Counties get firm counting instructions

Pinal County sees far fewer ballots dropped off at polling places. For example, the most any polling place received on election day in March was 86. Lewis, the recorder, initially told Votebeat that having a bipartisan team do this work at the county’s elections center would better guarantee that the count will be secure, accurate, and observable.

“We are erring on the side of caution here, for the best intent of the voters,” Lewis said last week. “Being on camera in central count made the most sense.”

Told about the various interpretations of the law on April 3, Kolodin told Votebeat that’s not the correct reading of the law. “It absolutely fucking requires a hard count at the polling site,” he wrote in a text message.

The letter Kolodin and Rogers sent to election officials on April 4 said the law requires the counting to happen “on the spot at the voting location” and emphasized there needs to be a count from each location, not just a total count.

Jen Marson, spokesperson for the Arizona Association of Counties, agreed with Kolodin. On April 3, she sent an email to election directors and recorders letting them know the new law “requires a hard count of the number of late earlies dropped off at voting locations, before those ballots leave those voting locations,” and saying “that was always part of the negotiations” for the new law. Votebeat obtained a copy of the email. The term “late earlies” refers to mail ballots cast in drop boxes or at polling locations on Election Day

In a response to Marson, Pima County Recorder Gabriella Cazares-Kelly questioned that determination, saying the law requires the ballots to be counted on election night, but “doesn’t specify where.”

Pima County is one of many counties that had already been counting such ballots on site at polling locations. But Cazares-Kelly doesn’t believe the new law requires it.

Barton doesn’t either.

“What Alexander Kolodin believes in his little heart does not matter,” Barton said. “That one particular legislator hoped to make the system of counting less effective, doesn’t mean the counties have to do it in a less effective way.”

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.