Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Arizona’s free newsletter here.

Many Arizona residents seeking to register to vote ahead of Tuesday’s primary were blocked from the voter rolls because of problems with the paper registration forms they used, according to a Votebeat analysis of longstanding issues with the forms.

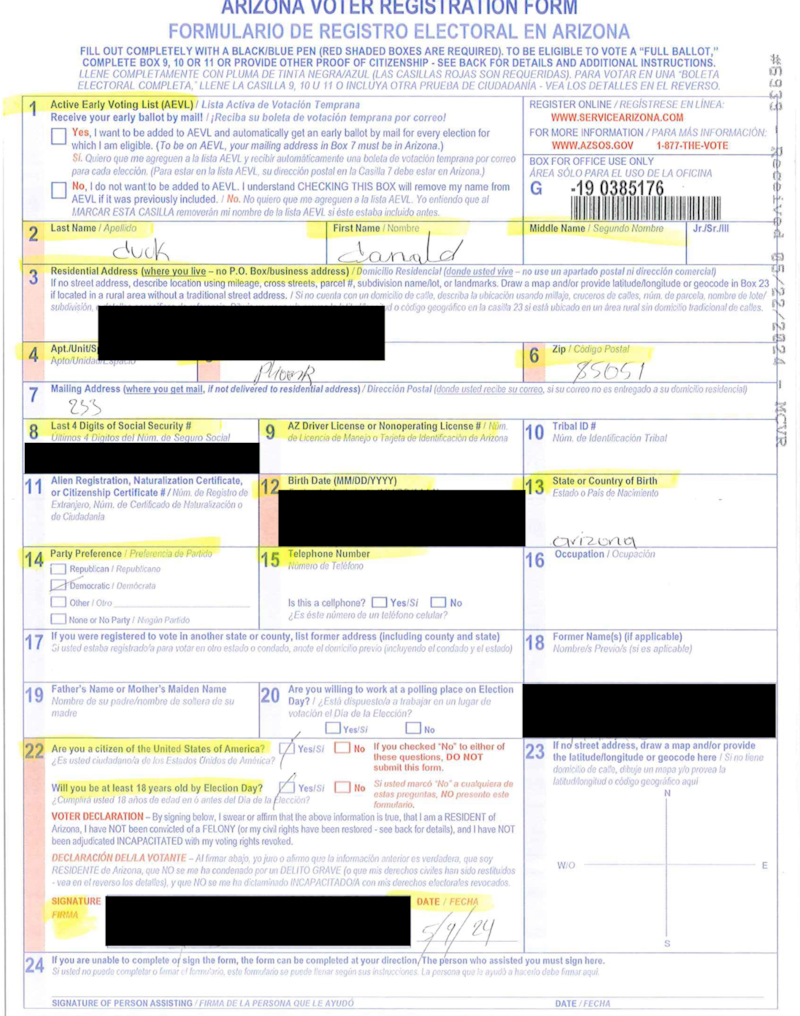

The paper forms are the type commonly distributed and collected by civic groups and political parties during voter registration drives. Election officials around the state value these third-party outreach efforts, but have said for years that forms they’re receiving often have inaccuracies or other deficiencies, such as a missing ID number, birthdate or signature, or a bogus name. Such lapses complicate the work of county recorders, and may disenfranchise even some voters who are already registered.

Votebeat was able to collect data that shows for the first time the extent of the problem. In Maricopa County, around a third of the voters who tried to register with a paper form in the week before a July 1 deadline were found to be likely eligible to register, but nonetheless had their registration blocked because of a problem with the form, according to new data obtained by Votebeat.

Around the state, as of late July, about 24,000 residents, including some already registered voters, had their registrations placed on hold until they could confirm or correct their information with local election officials; in 2020, Joe Biden’s margin of victory was about 10,500 votes.

Several county recorders and their staff said the inaccurate and incomplete forms overburden their small teams, which are legally required to process the forms, no matter how faulty. And if they can’t reach the voter to fix the problems, voters who may believe they are registered aren’t actually added to the active voter list.

Janine Petty, Maricopa County’s senior director of voter registration, said her office has the same mission as the voter registration groups — to register voters.

“But we also want to make sure that we are complying with the laws,” she said.

The forms present additional challenges in counties such as Apache that encompass tribal lands, which often lack residential addresses. Voters there might describe their location by physical or natural landmarks, and it takes a while to pinpoint where they live. Staff members there report having spent more than an hour on just one form trying to figure out where a voter lives.

Former secretaries of state have flagged these problems for more than a decade, but lawmakers are divided about how to try to solve them.

Republican state lawmakers have proposed creating new rules for voter registration groups, such as prohibiting them from paying workers for each form they turn in, or requiring disclaimers on third-party mailers to distinguish them from official government mail. Democrats and some civic engagement groups have opposed those measures, advocating instead for reforms such as automatic voter registration.

Pinny Sheoran, president of the League of Women Voters of Arizona, said her group has opposed the Republican proposals as too restrictive. But she also said she recognizes the gravity of the problem, and believes better training for the canvassers who distribute and collect forms is part of the answer.

She said her group’s workers are “hawk-like” in making sure the people they register complete their forms accurately. For a voter to go through the effort to complete the form but not be registered would be “a terrible shame and disservice to that voter,” Sheoran said.

Inaccurate forms cause problems for already-registered voters

Most Arizonans register to vote electronically, but political parties and advocacy organizations turn in thousands of paper forms across the state in the weeks leading up to the registration deadline for each election. For the July 30 primary, the deadline was July 1.

In the week leading up to that deadline, Maricopa County received 2,980 paper forms.

Of those, 1,038 were from voters not already registered to vote. But because of problems with the forms, only 682 of those people were added to the active voter rolls. Most of the rest were deemed likely eligible to register, but the county had to put their registrations on hold, or into what’s known as suspense status, until the voters fix the problems with their forms. These voters will not get a mail ballot if they have requested one, and they will need to fix the problem with their form before voting in person.

In some cases, voters who were already successfully registered to vote can run into problems if they try to make a change to their registration, or submit a duplicate form by mistake. If their new paper form is missing critical information — such as name, address, date of birth, or signature — the clerk is required to place their registration in suspense status until the issue is resolved, even though they were already registered before, according to a spokesperson for the Secretary of State’s Office.

State law requires that counties notify people when placing them in suspense status, the office said. But sometimes, the voter still doesn’t correct the flaw in time to get back on the rolls.

How one voter registration group trains field workers

The Maricopa data obtained by Votebeat backs up what election officials have long said — that some organizations are better than others at turning in complete forms.

One of the most successful during the time period Votebeat studied was Poder Latinx, a Latino civic engagement organization, which successfully registered around 92% of the people who filled out the form.

Poder Latinx’s Arizona state program director, Nancy Herrera, said the organization — which registers voters in six states — requires workers to undergo a full day of training on voter registration before they go into the field, with specific training on how to guide people through the form.

“We do take more time with our applicants because we want to ensure they are participants in the upcoming election,” Herrera said.

Herrera says Poder Latinx has weekly check-ins with field staff to answer their questions, and also tries to follow up with counties when dropping forms off to see if counties have flagged any flaws with their forms.

To prevent someone from filling out a duplicative form if they are already registered, workers ask the registrants questions, such as when they last voted, Herrera said.

Sheoran, from the League of Women Voters, said many of her members doing voter registration work in Maricopa County go through the county’s deputy registrar program to get trained on the laws and requirements. She believes all counties should institute a similar program for this purpose.

The Maricopa County Recorder’s Office encourages organizations engaged in voter registration work to go through that training.

Pima County Recorder Gabriella Cázares-Kelly, a Democrat, said her county tries to train the voter registration groups as much as possible, but high staff turnover makes it hard to ensure that forms are filled out correctly.

She cited one case where a voter had filed 21 separate forms with her office, apparently attempting to reregister or update their information.

But she said she believes the work that advocacy organizations do to educate and register voters is important, especially because Arizona doesn’t have automatic voter registration and she doesn’t have enough staffing to do significant voter outreach.

Cázares-Kelly believes the best solution would be allowing automatic and same-day voter registration. Those ideas are a longshot in Arizona with Republicans controlling the Legislature. But she said Republicans need to “stop pretending that it wouldn’t be helpful.”

Forms with fake names add to the burden

In Apache County, the recorder’s office has just three people to process voter registration forms. Some days, dozens will be dropped off by a given group, and staff members estimate that around 3 out of every 10 can’t immediately be processed because they are incomplete or inaccurate.

Petty said her office in Maricopa County often sees forms with incorrect information such as a birthdate that is off a few digits. Sometimes a form will come in for someone they believe is already registered, and it takes work to make sure it is the same person.

And then there are the forms that come in with names like “Mickey Mouse” or “Donald Duck.”

Petty and other election officials suspect that some circulators may be responsible for these because they get paid for each form they turn in.

State Sen. Ken Bennett, a Republican and former secretary of state, introduced a bill this year that would have banned voter registration groups from paying employees for each form they turn in, a practice he claims incentivizes fraud.

The bill was blocked in committee in the House, but he hopes to try again next year.

Voting rights groups generally object to new restrictions on groups that register voters, especially given that several states have already limited how such groups do their work, with sometimes harsh penalties for organizations that break the rules.

Since 2021, at least six states have enacted laws restricting third-party voter registration assistance, according to the Voting Rights Lab.

A Florida law enacted in 2023, for example, prohibited noncitizens from helping with nonpartisan voter registration drives and imposed a $50,000 fine on organizations that violate the law. A federal judge recently blocked portions of that law, after the League of Women Voters, Poder Latinx, and other organizations filed a lawsuit.

Prefilled mailers cause problems

In Yavapai County, Recorder Michelle Burchill said the biggest issue for her team this year has been the use of an old version of an official form that voters use to be placed on the active early-voting list.

The older form has former Secretary of State Katie Hobbs’ seal on it. Hobbs is now the governor.

Some voters have been getting a copy of the form in the mail, with their name, address, and birthdate prefilled. The problem is, half of the time, the prefilled birthdate is wrong.

Burchill said she isn’t sure who is sending out the form. Similar forms have long been distributed by political parties or advocacy groups that use commercially available information to develop mailing lists of potential voters.

But from speaking to voters, her staff has come to believe that some of them are returning the prefilled forms because they mistakenly believe they are required to.

Burchill said she strongly believes that no one should be permitted to send out prefilled forms. “These documents, often created with outdated voter information, inadvertently contribute to voter distrust and hinder the electoral process’s integrity,” Burchill said.

Tennessee enacted a law this year that bans organizations from prefilling voter information on mailers.

State Sen. John Kavanagh, a Republican, proposed a bill in 2023 at the request of Maricopa County Recorder’s Office that would require a disclosure saying any mailing sent out from third-party registration groups isn’t a government mailer.

In testimony to lawmakers, Aaron Flannery, government liaison for the recorder’s office, said that during a recent election cycle, the county had received about 3,300 forms from voters spurred by third-party mailers, and about 82% of those people were already registered, and needed no update to their records.

Flannery said the mailers lead to phone calls from confused or angry residents. “My husband has been dead for 11 years,” Flannery quoted one caller as saying. “Why are you trying to register him again?”

State Rep. Cesar Aguilar, a Democrat, said in a recent interview that his dad, who is a permanent U.S. resident but not a citizen, once received what he believed to be an official mailer saying he was eligible to register to vote, when he is not.

Aguilar said he isn’t sure that the Republican proposals would fix the problem. But he said he thinks there might be room for the Legislature to come together on a solution in future years.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.