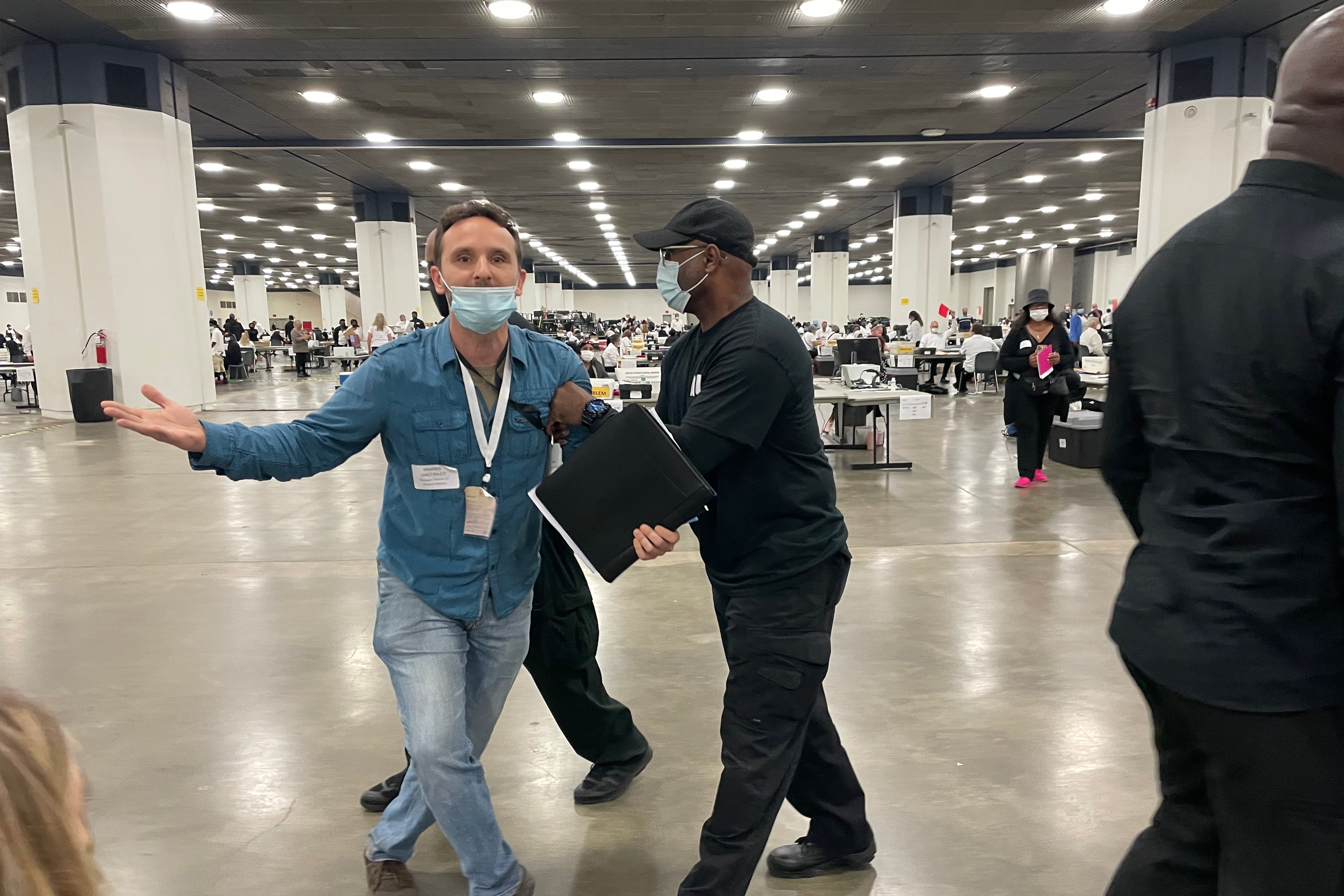

After a smooth day of voting with few shakeups and almost no problems reported by voters, the counting of Detroit’s primary ballots was interrupted late Tuesday night by a bizarre scene: Security ejected a GOP poll challenger from the Huntington Place convention center because, an official said, he was “harassing and agitating” election workers.

The man, one of a group of observers there at the behest of the local GOP, spent hours arguing about predetermined rules. He walked in and out of the counting area, offering colorful commentary on what he saw as unfair treatment and occasionally laughing about it. He insisted he be allowed into a secure counting area, then insisted he be given the names of several election workers. By 11 p.m., enough was enough, and he was escorted out by security.

“I did nothing wrong!” he shouted, defending his behavior as he was taken out of the counting room.

Dan Baxter, chief operating officer for the Detroit Election Department’s absentee ballots and special projects division, said the incident didn’t disrupt counting. It was the only such confrontation inside the center.

Other GOP-appointed observers who’d earlier been seen with the man defended him, saying he was doing his job as a challenger. One, who said the man had been training her to be a challenger, said the man had told her earlier in the day he’d been warned about his behavior. All refused to give their names. None of them caused additional commotion.

The man’s outburst stands in stark contrast to the rest of the day. Voters’ complaints about polling place hiccups were routine, minor, and predictable for a low-turnout primary in a midterm year. Eight precincts in Wayne County, for example, opened without electronic check-in tablets, but voters’ identities were verified manually and they still cast ballots successfully. And in Lapeer County, some ballots with misprinted marks had to be hand-duplicated in order to be scanned and counted.

Still, the Huntington Place incident, which was marked by conduct election workers called abusive, offers a potential glimpse at what to expect in November: standard voting administration, punctuated by drama from activists with agendas, said some observers at Huntington Place.

Tracy Wimmer, the spokeswoman for Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson said Wednesday her office was not aware of other places where challengers caused disturbances.

In the Detroit metro and across the state, in-person turnout was down and absentee ballots were up, with more than 1 million absentee ballots returned. Of the nearly 80,000 ballots cast in Detroit, more than half were absentee.

Total voter turnout in the city was estimated at 15% for the primary. At times, election workers outnumbered voters even in what are typically well-trafficked in-person voting precincts. And the voters who made it out to their precincts expressed confidence in the system.

“I’m positive about it,” said first-time voter Michael Watts, a concessions worker who cast his ballot on Tuesday at the Hamtramck Senior Center. “I think [the election] will be accurate.” His uncle beamed nearby. Dipping his toes into civic engagement has given him such a boost, Watts said he’s looking into options for college.

Even voters who had light frustrations were ultimately confident that their vote would be counted as intended.

Both Melia Monroe — who was handing out campaign literature at the senior center — and Dick Olson — who cast his ballot 15 miles away in Grosse Pointe Park — were frustrated their voting location had moved since the last election. “The old system worked well,” said Olson. “They are making it harder for people to vote in person.”

Still, he said, he has no concerns about accuracy or security. “I trust that my vote is going to count,” he said, adding that he has confidence in the city clerk’s office and the system overall. Grosse Pointe Park city clerk staffer Donna Costa said the change was out of the office’s hands — schools could no longer be used as polling locations, and workers were posted outside of the old location to redirect voters.

But most of the state’s ballots were sent in by mail, and here, too, things went smoothly.

“We’ve got a well-run operation here today,” said former Michigan elections director Chris Thomas at Huntington Place, formerly TCF Center, where Detroit’s estimated 43,000 absentee ballots were being counted on Tuesday night. Thomas has been hired by the state to serve as a consultant to Detroit’s election operations, and helped manage the counting process at Huntington Place.

Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, at her end of the day press conference, confirmed that the day had gone off without a major incident. She thanked clerks and others for their “hard work and diligence” resulting in a smooth election. “Please join me in thanking the thousands of clerks, local election officials and poll workers working long hours working this week to make Democracy work for everyone.”

This article is made possible through a partnership with Bridge Michigan, Michigan’s largest nonpartisan, nonprofit news publication.

Oralandar Brand-Williams is a senior reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Bridge Michigan. Contact Oralandar at obrand-williams@votebeat.org.