Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

Canton Township Clerk Michael Siegrist characterizes the 2024 election season as “the most challenging cycle ever” as clerks race to implement early in-person voting and other recent changes to state law designed to expand voting access for Michiganders.

Voter education, costs, logistics, and determining the most efficient means of running early voting are among the challenges, but Siegrist adds that he thinks the payoff is huge: Michigan voters now have a tremendous amount of access while the state maintains its election security.

The low turnout presidential primary is also offering a relatively low pressure environment before what officials predict will be a high November turnout.

“There was a substantial amount of anxiety, but in the end the Bureau of Elections was working hard and they really moved mountains, and a lot of us local election officials worked in tandem to move mountains to implement the rules,” he said.

The presidential primary marks the first statewide election in which Michigan has adopted the new rules required by Prop 2, a 2022 citizen ballot initiative approved by 60% of voters.

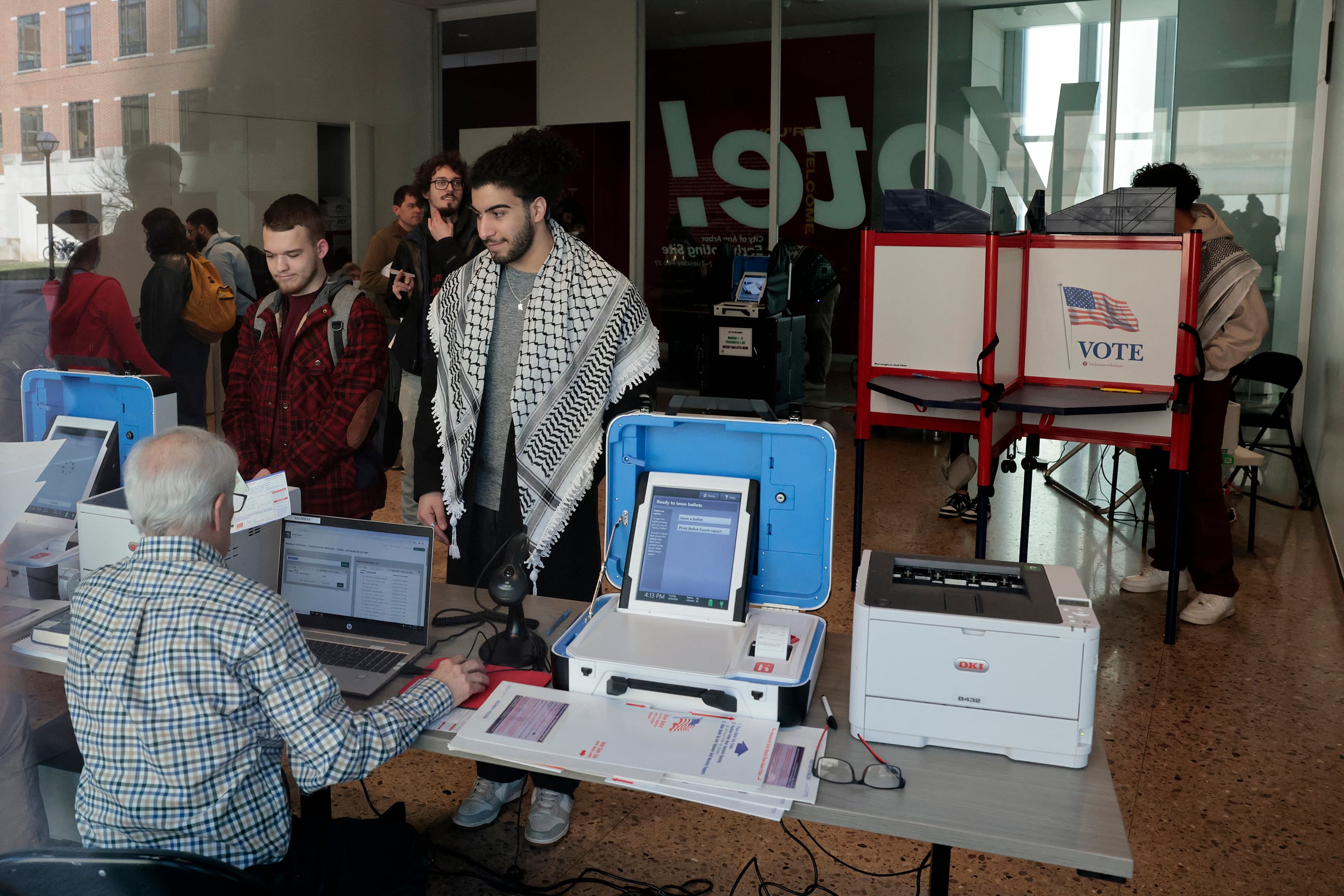

Among other provisions, it mandated nine days of early in-person voting, which began on Feb. 17 for the presidential primary, and runs until Sunday, Feb. 25. The new process gives voters the opportunity to place their ballot in tabulators, just as they would on Election Day.

The Secretary of State on Friday reported about 50,000 people statewide had taken advantage of early in-person voting, and over 7,300 of those voted on Monday, which was Presidents Day. Expectations are high for the weekend, clerks say.

How communities handled early in-person voting

Local clerks can implement early in-person with one of three approaches: go at it alone, enter into a municipal agreement with a small number of neighbors, or enter into a countywide arrangement in which county election officials coordinate the process.

“We left it up to clerks,” Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson said during a Feb. 16 press conference, “because a clerk in Houghton may have different things than a clerk in Rochester Hills in terms of their resources and what their voters need.”

State data shows the more-populous southeastern Michigan municipalities tended to go at it alone, and municipalities in more rural areas generally worked with their neighbors or entered into a countywide agreement.

Among the 33 of Michigan’s 83 counties that opted for a single, countywide early voting location is Ontonagon County, near the western tip of the Upper Peninsula. Just under 2,300 voters cast a ballot countywide during the 2022 midterms, and clerks are part-time. Staffing the early in-person voting sites is impractical logistically and financially, said McMillan Township Clerk Kay Richter.

“I will be truly and totally surprised if we have more than 50 voters during these nine days – and that’s with the entire county voting at one site,” she said. “It would be a total waste of time, energy, and money to do these sites independently for each township.”

Saginaw County, with 158,000 voters, will also offer just one place to cast an in-person ballot ahead of election day — in the city of Saginaw.

Many of the municipal clerks in southeast Michigan preferred to set up their own early voting because of the large numbers of voters those communities are serving. In Canton Township in Wayne County, the population is over 93,000. If it were a county it would be the 22nd most populous county, Siegrist said. A partnership that included Detroit, which has over 600,000 residents, and Dearborn and Livonia, which are among the state’s most populous cities, “would be too monstrous of an organization,” he said, noting those four cities comprise 40% of the county’s population.

Similarly, Ann Arbor is offering six early voting locations, while Washtenaw County is coordinating with all other municipalities to offer 15 sites in total.

But there are exceptions to this trend, like Oakland County, where 45 of 52 municipalities have joined in a countywide arrangement, and 19 early voting locations are in place for that portion of the county’s 1.04 million voters. Siegrist said it makes sense because Oakland County is populous, but does not have many large population centers, like Wayne County. Among those that are not part of the arrangement are Auburn Hills, Bloomfield Hills, and Rochester.

In Ingham County, which holds Lansing and a number of rural communities, municipalities mostly went at it alone because “We appreciate local control,” said Ingham County Clerk Barb Byrum. Exceptions included small municipalities like Onedaga, Aurelius Township, and Vevay Townships, which are working together

Similarly, in Kent County, home to Grand Rapids, clerks “felt strongly that it would be best for each clerk’s office to handle early voting locally, so as not to add another layer of confusion given all the changes to election laws since 2018,” said chief deputy clerk Robert Macomber.

Meanwhile, Benzie County’s municipalities are going at it alone, offering 14 early voting sites for its 16,900 registered voters.

In Macomb County’s Harrison Township, geography was a motivating factor for Clerk Adam Wit’s choice to run his own early voting. It is on a peninsula, borders Selfridge Air Force Base to the north, and is effectively bordered by Interstate 94 to the west. Its roughly 25,000 voters make it a larger district than many northern Michigan counties, Wit said.

“We have unique geography as a peninsula, and we have people who jump right on 94 and never go to a neighboring community, so just given that layout we thought this made sense,” he said.

Turnout for early in-person voting in the primary

Early in-person turnout has so far been low, clerks who spoke with Votebeat say, but they also said they expect it to pick up this weekend. There is also a learning curve as voters adjust to the new law, and county level clerks and some local clerks sent out mailers to voters to alert them of their new options.

“Any time there is a change in election administration, voters do have questions, and I think that’s why it’s important that information was mailed out,” Byrum said.

In Kent County, where more than 513,000 residents are registered to vote, 443 people voted on Saturday and 252 on Sunday. Ingham County had 472 early votes as of Tuesday.

In Harrison Township, 95 people voted as of Wednesday. While Democrats typically have been more open to early voting, Wit said his first early voter was a man who was on his way to speak at a rally for Donald Trump.

“One of his messages was ‘We need to take advantage of locking in votes early, and take advantage of the tools available to everyone,’” Wit said.

Absentee ballots remain popular even with the new in-person option, and absentee ballot requests are up significantly over the 2020 primary election – 1.3 million so far this election, compared with just over 863,000 in 2020.

The new rules allow absentee ballots to be delivered to a clerk and counted as an absentee ballot, or to be fed into a tabulator at a polling site and counted as an early in-person vote. As more absentee ballots come in this weekend, early vote figures could jump.

A sprint to prepare for early in-person voting

In a Jan. 11 letter to Benson, 74 clerks stated that they were “losing sleep” over the new rules’ implementation.

Clerks only received information late last year from the legislature on when the 2022 reforms would be implemented, Siegrist said. That required a significant amount of procedure and rulemaking, and technology to be updated in a short time period. The latter included updates to the legacy qualified voter system so it was ready to handle the changes, and adoption of electronic poll books to check in voters at polling places. Training wrapped up just ahead of the early vote period, generating some frustration among clerks.

“It is requiring us to adapt and learn how to pivot in real time,” Siegrist said. He added that he could not speak for everyone, but he felt he was prepared for the election.

Clerks who spoke with Votebeat said they were confident they would be reimbursed by the state for their expenses – the state has set aside $30 million for the new laws’ implementation and equipment. Others have said they will need to spend local taxpayer money to meet the demands during the November general election, when costs are much higher.

Still, clerks say they are confident in how they are handling the election.

“We’re feeling good about it – clerks step up, and get the job done,” Byrum said. “[Across the state] we have some amazing election officials who will make sure that voters are assisted and afforded the opportunity to exercise their right to vote.”

Votebeat contributor Tom Perkins is a freelance reporter in Hamtramck, Michigan.