Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Michigan’s free newsletter here.

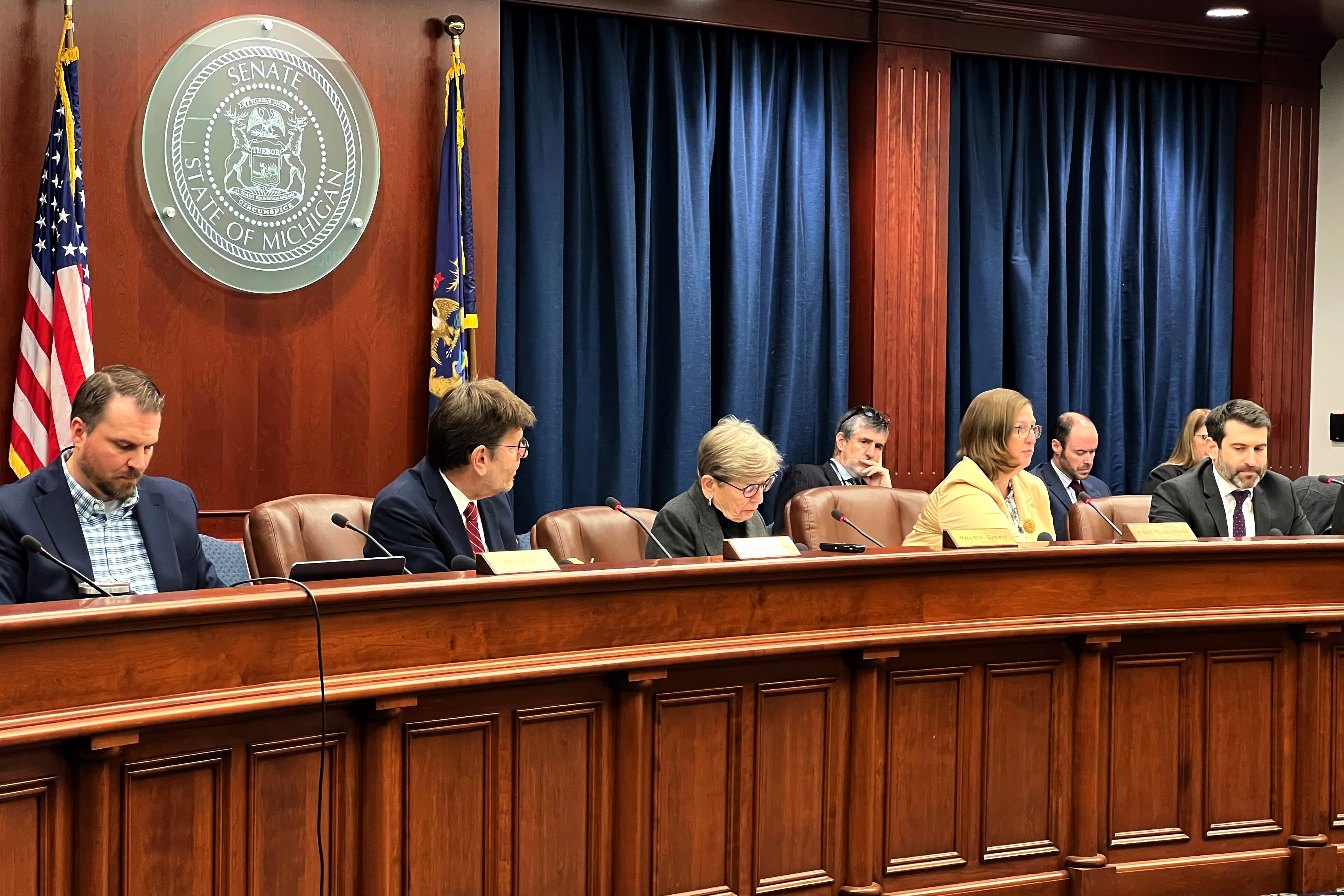

Michigan’s 2024 general election is certified, making the more than 5.7 million votes cast across the state official.

The certification itself was smooth, a marked difference from 2020, when one Republican canvasser abstained from the certification vote after casting doubt on the validity of Wayne County’s results. This time around, no one protested the results or suggested that certification could be optional. Both have happened in past certification meetings.

But more than ever before, the public and canvassers alike sought to understand every piece of the process: every hiccup, every law, every tabulator program.

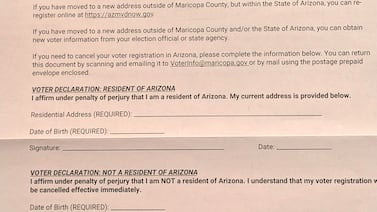

Public comment before the State Board of Canvassers largely focused on the Ann Arbor resident who cast a ballot despite not being a U.S. citizen. (In that case, 19-year-old Haoxiang Gao has been accused of two felonies, charges that are working their way through the court system.)

Other questions, primarily from the canvassers themselves to Bureau of Elections Director Jonathan Brater, focused on the nitty gritty of how elections work. How are tabulators programmed? What is an overvote? How were the errors in the unofficial results caught in the canvassing process?

The desire to understand these hidden elements is a new normal, sprung out of the confusion and disarray of 2020 — and it’s not a bad thing, officials say.

“The more that we can educate people, the more we empower people,” Jeannette Bradshaw, one of the two Democrats on the four-member State Board of Canvassers, said shortly after she and her colleagues unanimously voted to certify the election. Bradshaw asked a number of questions to help understand the process herself, she said, and educate anyone else who might be interested.

Not long ago, for the typical voter, canvassing was the most important process they had never heard of. At the county level, the canvassing process entails looking at every precinct’s results, fixing any human errors along the way, and confirming the winners; at the state, it is a matter of further validating that those results are correct. The jobs are largely ministerial and relatively unexciting.

And the 2024 election was especially unexciting. Brater told the board that despite significant recent changes to election procedure, voting ran relatively smoothly. It was the first presidential election to offer voters the chance to vote by absentee ballot, or in person either early or on Election Day, and millions of people were able to cast their ballot without a problem.

“The system worked in 2024, just as it did in 2022 and 2020 and other recent elections,” he said.

But canvassing offers voters and officials alike the chance to look at how well pieces of the system work, even if there is nothing to be changed. It allowed the state canvassers to get a deeper understanding about how human errors led to more scrutiny of unofficial results from Calhoun and Macomb counties, although the problems in both were quickly fixed. It also allowed Anthony Daunt, a Republican on the board, to register his concern over the potential for abuse in same-day registration.

He said that many arguments about noncitizens voting in U.S. elections are “in many ways nonsense and poisonous to the system” — the canvassers cannot do anything about that.

But he said he would like to see something from the legislature or the secretary of state’s office to address the concern, although he didn’t have any specific suggestions. The U.S. Supreme Court has held that people may vote in federal elections without providing documented proof of citizenship, but some states are considering laws to ask for more.

“Those are the types of things that create a climate for ‘conspiracy theories,’” he said. “If we don’t have an answer for that and a solution, I think it just festers.”

Examples of people who are not U.S. citizens casting ballots are extremely rare, and the potential risks are high, including felony charges and loss of legal residency status. As Brater pointed out, there is no single list that officials can use to compare with the Qualified Voter File — Michigan’s file on all voters across the state — to see who might not actually be a citizen.

Michigan instead largely depends on the criminal justice system “as a method of enforcement in deterrence,” Brater said.

It’s likely that questions about that, about canvassing or tabulators, or about any other part of the election are likely to reemerge, board members said, simply because it’s a complex process.

“I think there’s a lot more public education now, and there’s more still” to be done, said Richard Houskamp, vice chair of the board and a Republican. “We’ve had more access, more transparency. I think it’s the key. And as the technology changes, there’s going to be more questions.”

Hayley Harding is a reporter for Votebeat based in Michigan. Contact Hayley at hharding@votebeat.org.