Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Michigan’s free newsletter here.

When Lama Ali Ahmad became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 2021, she was eager to become a voter, too.

In Lebanon, where she’s from, elections were often derailed by crises. But here, she had faith in the process. She registered and voted in a municipal election the same day. That night, she gathered her family at her Dearborn home for a special dinner of steak, chicken, and tabbouleh, and told them how good it felt to finally be heard.

“That was the moment where I really felt that I am an American citizen,” she said.

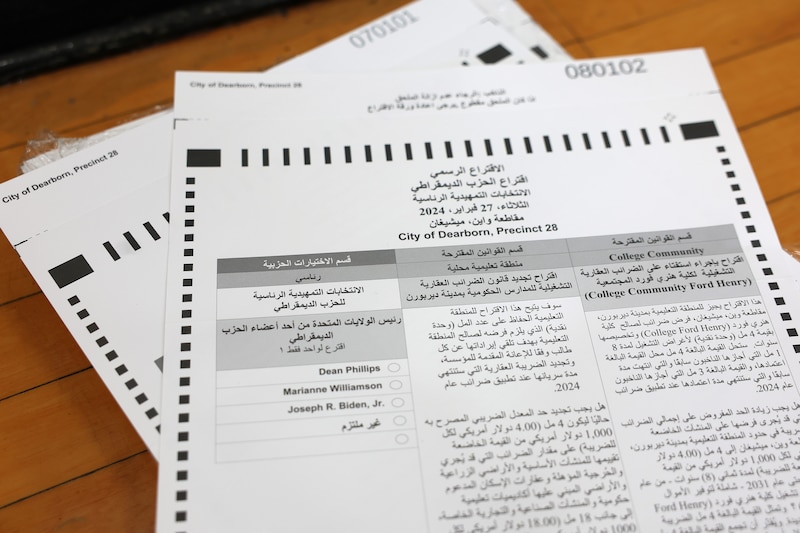

Last year, she celebrated another civic triumph: Voting on a ballot printed in Arabic, her first language.

The experience wasn’t perfect, said Ali Ahmad, who also speaks English and French. The Arabic translation of instructions and ballot questions was more formal than familiar and even awkward in places. But the impact on her was profound.

“I felt like I was at home when I voted in Arabic,” she said.

The translated ballot was available because of a local measure passed in Dearborn, a Detroit suburb with a high concentration of Arabic speakers. Hamtramck, another Detroit-area city with a large Arab-American community, has a similar local law requiring voting materials in Arabic.

But while Arabic is spoken all over Michigan, and is one of the most commonly spoken non-English languages in the U.S., there’s no Michigan or federal law that requires ballot translation into Arabic for people who would benefit from it. Federal voting rights laws do require ballot translations for many other languages, but they emerged at a time when Arabic wasn’t yet widely spoken in the U.S., and they were written restrictively to include only a narrow list of language groups.

That means that in communities across the state and country, Arabic speakers are excluded from the kind of voting access that people of other language groups are entitled to. In Michigan — where Arabic is the third most common language after English and Spanish, spoken by more than 171,000 people (with more than 80,000 of those who report speaking English less than “very well”) — it’s up to individual municipalities to decide whether to require Arabic translations, and then they have to figure out how to arrange them. Translations are costly and difficult to produce, especially in a way that’s familiar enough for everyday speakers to understand.

Dearborn Deputy Clerk Megan Lizbinski said the city has seen voters ask for an Arabic ballot, only to return and request the English version instead because the text in Arabic proves too confusing.

Experts say that if more cities begin doing the translation work together — sharing resources, translators, and templates under state leadership — the process could become cheaper, better, and more accessible for everyone.

Section 203: Voting rights law leaves Arabic out

The federal laws on ballot translations are contained in Section 203 of the Voting Rights Act, a part added in 1975. The section aimed to protect millions of people considered to have been “effectively excluded from participation in the electoral process” because of language, and initially covered a finite set of language groups: Spanish, Asian languages, Native American languages, and Alaskan Native languages.

Section 203 was a breakthrough for a country where many states had long used literacy tests to bar certain groups from voting. But over its 50 years, the law has retained its narrow eligibility criteria, and hasn’t always kept pace with demographic changes.

For a community of non-English language speakers in a particular area to qualify for a translation requirement under Section 203, they must be below certain thresholds for English proficiency and educational attainment, based on U.S. Census data. The list is updated every five years — the next revision comes in 2026 — and most communities don’t make the cut.

In Michigan, just four areas are subject to federally required translations: Clyde Township near Port Huron, and Fennville and Covert Township in the southwest, must translate into Spanish. Hamtramck is required to translate its materials into Bengali.

There’s little political will to broaden the federal criteria, experts say. But state and local governments have more room to act — and more recent success. Experts and advocates hope that will be the path forward for Michigan to adopt a translation policy that better reflects its current voter base.

Michigan Voting Rights Act called for expanded translations

State lawmakers have tried. Last year, Democratic legislators introduced the Michigan Voting Rights Act, a package of bills aimed at expanding ballot access. Among other things, it would have changed the criteria for a guaranteed translation, requiring many more communities to provide election materials in additional languages.

Coldwater, for instance, a city of around 14,000 in south central Michigan’s Branch County, would have had to offer its election materials in three languages, clerks testified at a House hearing. The city currently provides no non-English materials.

Local election officials didn’t oppose the idea of more translation. But they worried about the potential cost. State officials said the Department of State would pick up most of the tab, but there was no funding guarantee in the bills.

Coldwater budgeted around $33,000 for elections this fiscal year. Printing in two additional languages would have cost thousands more — and that’s before paying translators, running security tests on each version of the ballot, and other related expenses.

But the legislation ultimately died when Democrats failed to pass the package before the session — and their control of both chambers of the legislature — ended. The conversation about expanded language access largely died with it. Rep. Rachelle Smit, the Martin Republican who now chairs the House Election Integrity Committee has made it clear she has no interest in reviving the legislation.

Michigan does provide other language support for voters. The Secretary of State’s website offers information on voting in 19 different languages — the voter registration form alone is available in Spanish, French, Somali, Vietnamese, Russian, Dari, Arabic, Pashto, Bengali, Amharic, Mandarin, Japanese, and Korean. Voters are allowed to bring support (including translators) into the voting booth with them, and some communities use phone hotlines for live language help. Others rely on bilingual poll workers, often hired with state assistance.

But other states go further. California, for instance, requires translated ballots for any precinct where more than 3% of voting-age residents are of the same non-English language, compared with the federal standard of 5%.

In Los Angeles County, the largest voting jurisdiction in the country, that includes the languages covered by the federal requirement — Cambodian, Chinese, Korean, Spanish, Filipino and Vietnamese — as well as Armenian, Bengali, Burmese, Farsi, Gujarati, Hindi, Indonesian, Japanese, Khmer, Mongolian, Persian, Russian, Telugu, and Thai for certain precincts under state requirements. Other communities across the state are translating election materials into Urdu, Syriac, and Arabic.

A new poll finds that most Californians want the state to go even further, with 87% of respondents who spoke limited English saying they would be more likely to vote if they had a ballot available in their preferred language.

In Hawaii, where all elections are conducted by mail, mail ballots must include instructions on how to access translation services in Hawaiian and at least five other non-English languages.

Minnesota state law requires voting instructions at all polling places to be translated into the three most commonly spoken non-English languages: Spanish, Hmong, and Somali. The state also requires translators at precincts with significant language minorities, meaning voters can get assistance in German, Russian, and other languages.

“As I see it, it’s not about English proficiency really,” Minnesota Secretary of State Steve Simon told Votebeat, explaining that his mother, who was from Austria, spoke English fluently but still preferred to read complicated material in her native language.

“I think most humans are that way. It’s not that she lacked English knowledge, and it’s not as if Hmong speakers or Spanish speakers or Somali speakers or Russian speakers can’t read English. The opposite is often true,” he said. “But when it comes to technical instructions, you want to convey information in a language that best connects with a person.”

People don’t always immediately know that information is available in another language or even think to ask. But when those materials are consistently offered, they help drive civic participation. The translations bring voters closer to truly understanding what they’re weighing in on.

It’s why Lizbinski, the deputy clerk in Dearborn, believes the benefits of offering translation into Arabic “far outweighs the costs.” Those costs are significant: typically around $32,000 for a general election, and closer to $87,000 for a presidential primary, where there are three distinct ballot types. (Those costs, officials say, are likely to rise in future elections.)

How a statewide model could help in Michigan

Between 1980 and 2021, the number of people in the U.S. who speak Arabic at home grew nearly sevenfold — outpacing most other language groups — according to Pew Research Center, and the community continues to grow rapidly in Michigan, beyond the major hubs like Dearborn, said demographer Kurt Metzger.

As long as that pace continues, local election officials will have a tough time meeting the language needs of Arabic-speaking voters. Shams Al-Badry, civic engagement manager at the Dearborn-based Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services, said that history shows that clerks are willing to make the changes but hesitant to shoulder the cost alone.

But experts agree that if the state served as a kind of linguistic clearinghouse, offering ballot translation through a statewide system, rather than relying on individual communities, that problem could be eased.

And if the state covered the expense, Al-Badry said, local officials could focus on delivery: getting translated ballots into the hands of the voters who would benefit the most.

Even native English speakers may have a hard time understanding complex ballot measures. “Now bring in someone who doesn’t fully understand the language … and expect them to vote their conscience,” she said. “That’s really difficult.”

That’s what motivates Ali Ahmad, the Dearborn resident, who is still navigating what it means to be an American citizen. She jokes that she’s not 100% sure what a county treasurer does all day, or why she has to vote on one.

But she’s helping others navigate the system as lead community organizer for the National Network for Arab American Communities. She translates voter guides, educates new citizens, and urges her eligible family members to vote as well.

She appreciates the state’s recent changes to expand voting rights, such as early voting and less restrictive absentee voting.

And “this seems like the next good step in making voting accessible,” she said, “making sure everyone can vote in their language.”

Hayley Harding is a reporter for Votebeat based in Michigan. Contact Hayley at hharding@votebeat.org.