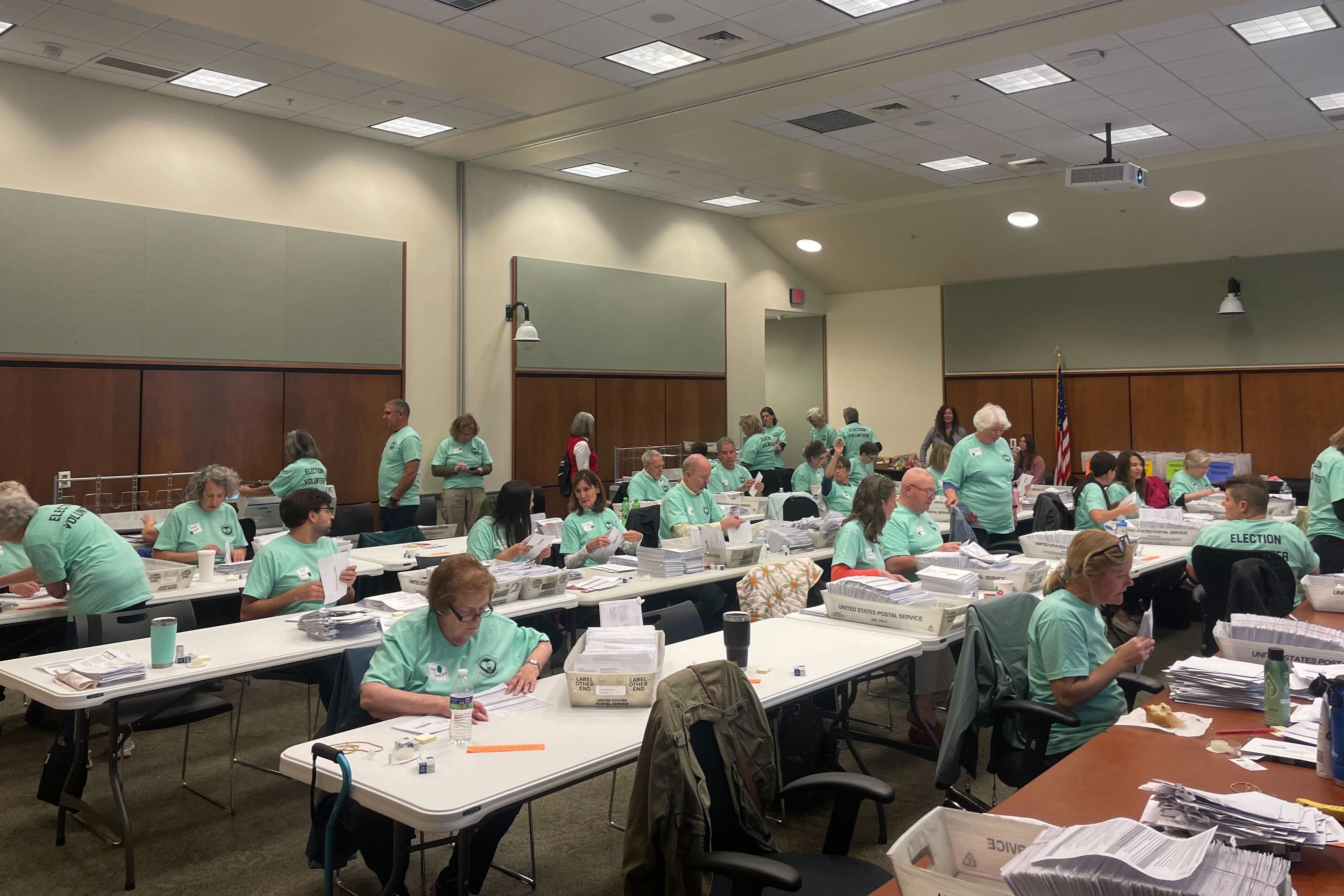

Despite some initial concerns with a new requirement that most Pennsylvania counties tally their mail-in ballots nonstop, election workers plowed through the job Tuesday and Wednesday while reporting no major problems.

Passed by the Legislature late last summer, Act 88 offered grants to counties for election administration costs. But there was a catch: Counties that took the money could not stop counting mail ballots until every one had been tallied. All but four of the state’s 67 counties took the state up on the offer.

Many counties already had some experience with nonstop counting from past elections. But the legal requirement adds new pressure and prompted counties to develop new processes to ensure they comply with it, underscoring all the ways in which election officials in the state are still adjusting to manage the relatively new mail-in voting system there.

“We have done that in the past. That’s not new to us,” said Commissioner Ray D’Agostino, chair of the Lancaster County Board of Elections.

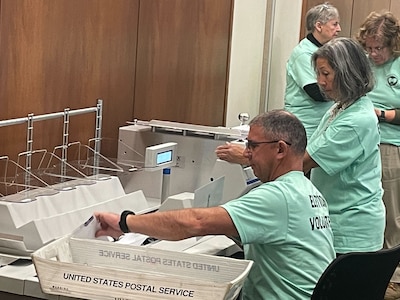

By staggering shifts of a few dozen workers each, Lancaster County was able to comply with the requirement for an uninterrupted count. As with other counties, new equipment like high-speed envelope openers purchased with grant funds helped make the continuous count possible.

The Pennsylvania Department of State had not received any reports of counties struggling to comply with the requirement as of late Tuesday night, said spokesperson Amy Gulli.

Counties were required to start their counting at 7 a.m. Tuesday, and most of them nearly finished the job before they got into the wee hours after polls closed. By 1:38 a.m Wednesday, 49 counties had counted 90% or more of their mail-in ballots, according to data from the Department of State. By 4 p.m. Wednesday — the latest data available — that figure was up to 55 counties

Each county has its own detailed procedures for the counting process. Some election officials prioritized getting results up quickly. Others were more geared toward the need to potentially respond to post-election challenges.

This changed the timing of the count in ways that didn’t necessarily reflect the volume of mail ballots a particular county had received.

York County, for example, finished counting the bulk of its roughly 37,000 ballots by mid-afternoon on Election Day. Greg Monskie, the county’s chief operations officer, said Tuesday, with pride, that the county would post its results before midnight, just as it has done in past elections.

York’s process is to remove all ballots from both the outer return envelope and inner secrecy envelope and flatten them out — and only once that has been done with all ballots do workers begin scanning.

The county “had done a time study on how long each part of that process takes and organized the process around that,” Monskie said.

Its neighbor, Lancaster County, meanwhile, had some workers scanning ballots while others opened new envelopes, and the county continued to count ballots after midnight despite having only roughly 6,000 more than York.

To Lancaster’s east, Chester County was still counting at 2 p.m. Wednesday and had only gotten through approximately 44,000 mail ballots, with roughly 25,000 more to go.

Karen Barsoum, the county’s election director, explained that the county was behind its peers because of its unique process for counting mail ballots. It takes longer, she explained, but is focused on her preferred metrics of organization and meticulously detailed chain of custody.

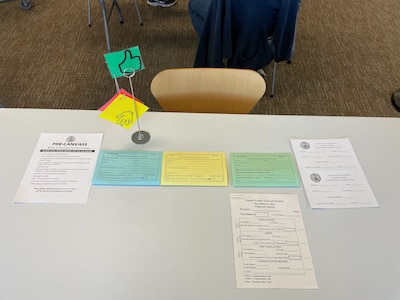

Mail ballots for each precinct in Chester County are divided into three batches depending on when they were received. As the ballots in those batches are first examined, opened, and tabulated, workers can flag any they think may require further legal examination by filling out color-coded forms.

Accompanying the batch through each step of the process is a chain of custody form that tracks how many ballots move from step to step. Successfully scanned ballots go into their own file box, with a label indicating the precinct, number of ballots, which tabulator the ballots were scanned on, and what USB drive number the tabulator data was recorded onto, for eventual transfer to a computer connected to the internet.

Barsoum explained that while this method takes a little longer, it is designed to ensure there is documentation and organization at every step, so that if challenges, recounts, or other issues arise, the office will know exactly what material needs to be reviewed and where it is located.

“I would love to patent this, because this is one of the processes I am really proud of,” Barsoum said.

The difference between the counties’ processes underscores something about Act 88, she said. The law told counties what they must do, but not how they must do it, leaving it largely up to them to decide how to get from A to B.

“I know we might not be the fastest,” Barsoum said, “but I know if something happens we will be the first one to be able to respond in a very successful manner… [The goal is] quality over speed.”

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org.