Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

Pennsylvania counties that benefitted from $45 million in state funding to help cover election costs say they are happy with the investment and plan to apply for a new round of grants beginning next month.

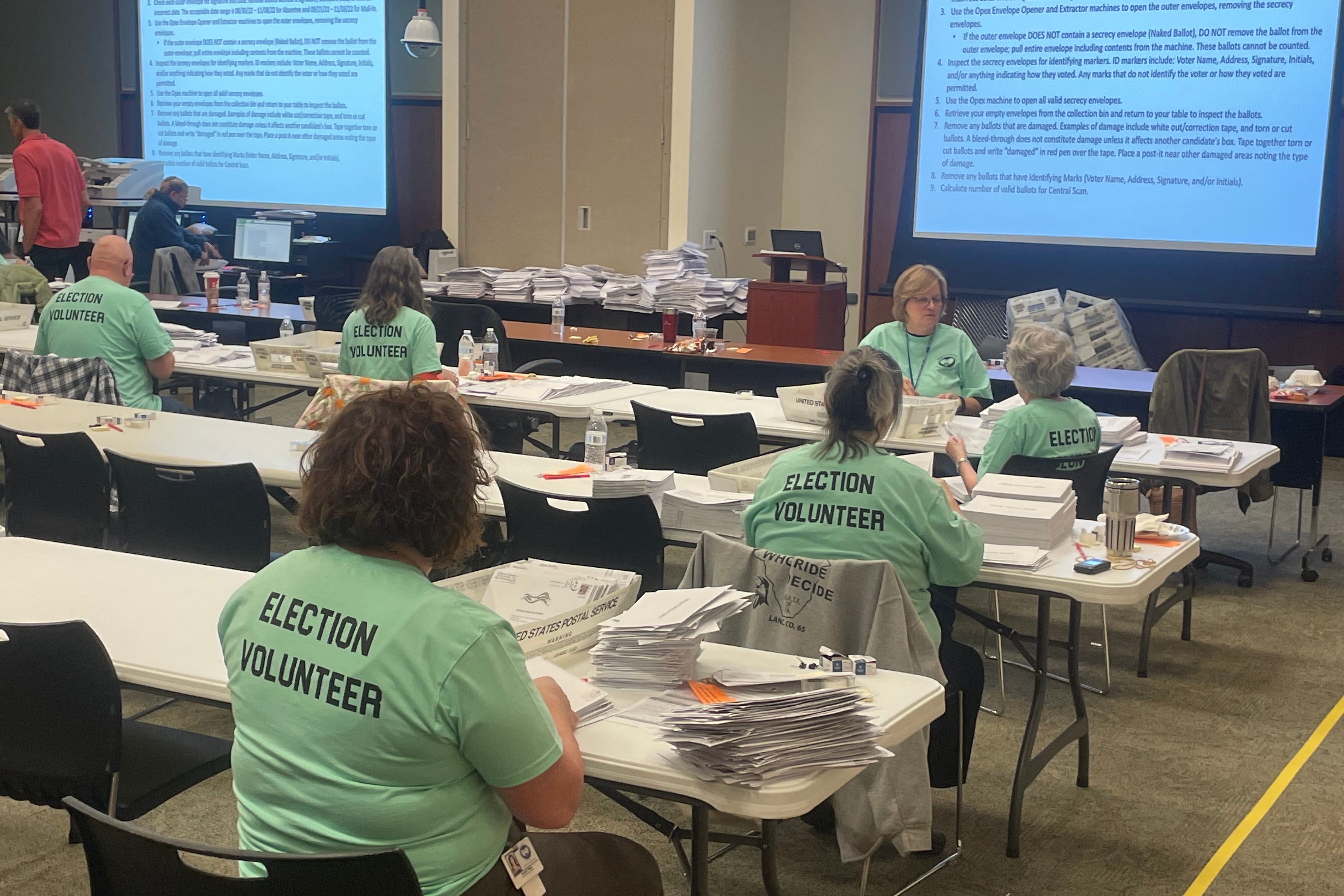

In the lead-up to last year’s November election, counties spent much of their share on expenses such as mail ballot sorting machines, rental trucks to transport voting equipment, and poll worker pay, according to new data from the Department of Community and Economic Development.

The money was made available through a bipartisan law known as Act 88, which represented one of the state’s most significant investments in election administration ever, and counties are looking forward to reapplying for the grants when applications open up in August.

Still, at least two counties say they will again decline to apply because of the strings that are attached to the grants. That includes a requirement that counties continuously count mail ballots beginning on Election Day and not stop until the task is finished.

The strings — and the dollars — are the product of a deal last July between the then-Republican-controlled state Legislature and former Gov. Tom Wolf, a Democrat, to provide election dollars to counties in exchange for a ban on outside grants for election costs.

“Absolutely it was useful,” said Matthew Repasky, elections director in Columbia County, which received roughly $200,000 and spent about a third of the money on the secure transportation, storage, and maintenance of voting equipment. Repasky looked at his budget from the previous year and identified expenses that lined up with the program’s spending categories, saving county dollars.

Complete spending data is not yet available as counties are still working on reports for money spent during the May primary. But reports from the November 2022 midterm election, which Votebeat and Spotlight PA obtained from the state via a public records request, show counties spent roughly $20.6 million, primarily on staffing costs, as well as secure transportation and storage of election equipment.

Counties most commonly spent the funds on payments to poll workers, which accounted for $8.7 million, the reports showed. Staffing costs are typically one of the most expensive parts of a county’s election. While poll worker pay was the largest spending category for the grants, many of the expenses in other categories were also related to staffing costs, the reports show.

Some counties bought big ticket items, such as Luzerne’s $371,565 purchase of an Agilis Mail Ballot Sorting System. Many counties made large purchases in 2019 when the state shared some of the cost of upgrading voting machines, which was required by a legal settlement.

“There are a lot of costs that go into running an election,” said Lisa Schaefer, executive director of the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania.

Counties had until June 30 to spend the grants. Each county was eligible for a specific amount determined by the size of its voting population.

Philadelphia had the highest allocation, at $5.4 million, while rural Cameron County had the lowest, at slightly more than $15,000.

“It was useful to help cover the voting procedures that are now in place because of [no-excuse mail-in voting], with the additional mail-in ballot processes, printing, and postage,” Jason Mihal, election director in Greene County, said. “It does help a lot with that.”

Applications for the second round of funding will open next week.

Some counties opt out

Only four counties — Bradford, Crawford, Montour, and Susquehanna — did not take the grant money last year, with most telling the Philadelphia Inquirer at the time it was due to the continuous count requirement.

At least two will not be applying again, for the same reason.

“We don’t have the personnel to meet the count requirement,” said Ryan Craig, elections director of Montour County, a central Pennsylvania county with fewer than 12,000 registered voters. “We don’t even have enough [ballots] to justify continuously counting.”

Crawford County also won’t apply this year, Commissioners Eric Henry and Francis Weiderspahn said. The county prefers not to hire additional staff outside of the elections office to comply with the continuous count requirement, which they view as a security risk.

“Whenever the state has these ideas, we just wish that they would talk with the people that have to follow them,” Henry said. “We just wish they would come ask our opinion before they go change laws or make grants.”

Officials in Bradford and Susquehanna counties did not respond to questions about their plans.

Counties look ahead to next round

In 2020, Pennsylvania received $25 million in election grants from the Center for Tech and Civic Life, which itself was heavily funded by Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg. The grants drew criticism from conservatives as having disproportionately gone to Democrat-heavy counties — although all 67 were invited to apply — leading to Act 88’s ban on outside election dollars.

As for the continuous counting requirement, many counties had been effectively engaged in this practice since Pennsylvania’s no-excuse mail-in balloting law went into effect, and the requirement doesn’t seem to have posed a significant challenge to most of them.

“That was something we were already doing,” Repasky said. “So that was not a burdensome thing.”

But, “just because they made it work doesn’t mean it’s the best way to run the election either,” Schaefer said.

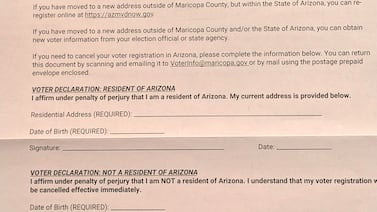

The County Commissioners Association has called repeatedly for the state to pass a law allowing pre-canvassing of mail-in ballots before Election Day, as other states with robust mail voting systems do. Pre-canvassing would allow counties to begin the most laborious part of the process — opening envelopes and flattening ballots for scanning machines — earlier, allowing counties to report unofficial election results sooner.

Counties are now in the process of creating their 2024 budgets, and some are incorporating the state money into their plans.

Melanie Ostrander, election director in Washington County, said Act 88 was passed too late last year for such planning, so instead she used the dollars mostly to offset already-budgeted costs such as mail ballot printing and staff time.

But this year, she has specific plans for the funds. Anticipating the continuation of a national poll workers shortage, she wants to use the state money to increase poll worker pay.

“I’m hoping it continues as it was presented to us — every year we will be able to apply and receive around the same amount,” she said.

Schaefer had expressed concern earlier this month that the ongoing budget impasse in Harrisburg would affect when the state would disburse this year’s money to the counties. She said last week she had not yet received clarification from DCED on whether the money will be in place on Sept. 1, when counties will be expecting it.

A spokesperson from DCED told Votebeat and Spotlight PA Thursday that regardless of what happens with the budget impasse, money will be available in the Election Integrity Grant Program account on that date to fund eligible applications.

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org