Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

Even before the sun was up on primary election day, Devin Rhoads was putting out fires.

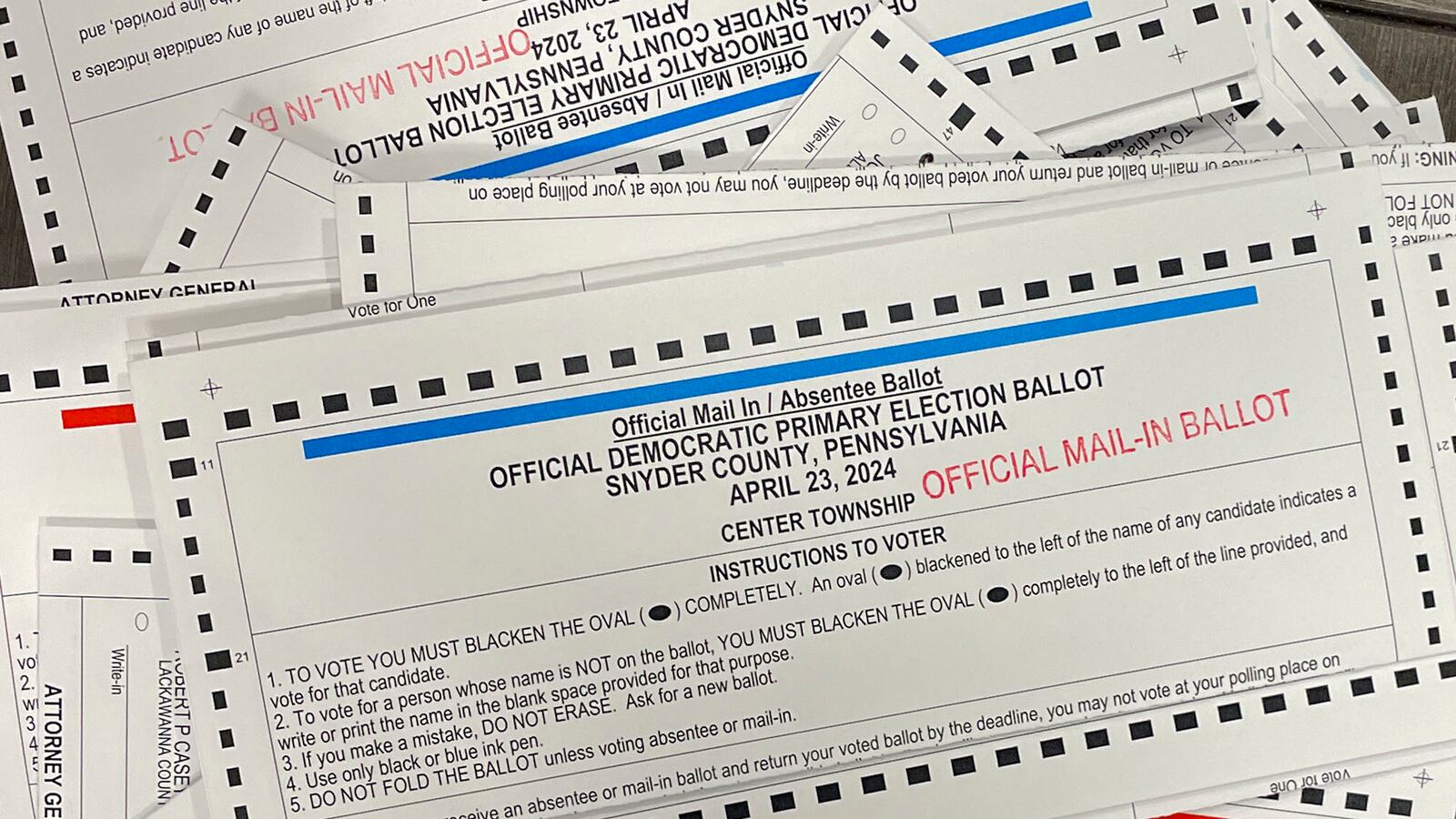

A precinct in Selinsgrove — a borough in rural Snyder County along the Susquehanna River — had accidentally received the provisional ballots intended for another precinct. Provisional ballots, which are specific to each precinct, are needed for voters whose eligibility is in question but who still want to vote. Without them, these voters can’t cast a ballot.

As election director for the county, charged with overseeing all 25 voting locations, Rhoads was the one who had to correct the problem.

“That’s an easy fix,” Rhoads said, recalling his reaction to the 6 a.m. phone call. He hopped in his tan Chevy Suburban and shuttled between the precincts to swap the materials, averting any problems before the poll opened.

Rhoads is one of many new election directors around Pennsylvania, and as the eyes of the nation again turn to this swing state in November, there is more pressure than usual on him and his peers to make sure things run smoothly.

Snyder County has gone through four directors in the past four years, but it’s not an outlier in terms of turnover.

Since 2020, the state has lost dozens of county election officials, and, along with them hundreds of years of total experience heading into the presidential election. The turnover has led to an increase in ballot and administrative errors across the state, and Secretary of the Commonwealth Al Schmidt said it is one of his “biggest” concerns for 2024.

Schmidt has good reason to be concerned. With election administration under a microscope, even unintentional minor mistakes receive heavy scrutiny.

During the 2022 election, a ballot paper shortage in Luzerne County resulted in an investigation by the district attorney and a congressional hearing. Last November, a programming error in Northampton County sparked conspiracy theories that the county was flipping votes.

Rhoads doesn’t dwell on the prospect of something going wrong.

“I just kind of concentrate on what I’m doing,” he said. “There’s no point worrying about ‘what if?’ We’ll just deal with it as it comes.”

Rhoads draws his confidence from the elections office staff around him, some of whom have served as interim directors. They’re available to answer questions, as is a former longtime director who has been mentoring Rhoads. Their chief advice has been to keep in mind that all problems are solvable.

“Maybe I’m a Pollyanna, and that’s served me well so far in life,” he said. “Anything and everything can be fixed. Step back. Take a breath. What’s the problem? What needs to be fixed?”

A steady presence in Snyder County

Rhoads, 53, is a lifelong resident of Snyder County.

He’s voted in nearly every election since he was 20, all at the same precinct — an old one-room schoolhouse surrounded by farmland.

“For me, voting in the cow pasture is the only voting I’ve known,” he said, using his affectionate nickname for the precinct.

Elections are a new line of work for Rhoads. His original career choice was veterinary medicine, after he graduated with a biology degree from Roger Williams University in Rhode Island in 1992. For 17 years, he worked as a veterinary technician and still has a love for animals.

The farm he owns and lives on is also home to eight sheep, three collies, a cat, a miniature donkey, chickens, guinea hens, and ten peacocks.

But after leaving veterinary services and working more than a decade in administration at Bucknell and Susquehanna universities, he entered the third phase of his career by becoming the county’s election director in May 2023.

Like many counties, Snyder has cycled through several directors since 2020, when a director with two decades of experience left. Rhoads is the fifth.

Commissioner Joe Kantz, who chairs the county’s election board, said that when Pennsylvania passed its no-excuse mail voting law in 2019, it compounded the amount of work directors had to do. They burned out quickly, he said.

“That’s a whole ‘nother … dinosaur of a workload, and so I think the additional stress that came with that takes the right people,” he said.

“We’ve been fortunate now,” Kantz said. “Devin is a great fit, and he seems to understand what he’s doing, and he appreciates the importance of a secure election, and he takes that to heart.”

Rhoads said he took the job out of a sense of civic duty and because he knew the commissioners needed someone ready to tackle the challenge.

He worries that voters hear so many bad things about elections and don’t trust them. But maybe if they at least know him, he said, and “if I can make people feel good and safe and secure, it’s worth it.”

On primary day, the phone keeps ringing

Snyder County has fewer than 23,000 voters, but even in small counties, an election day means nonstop work for directors.

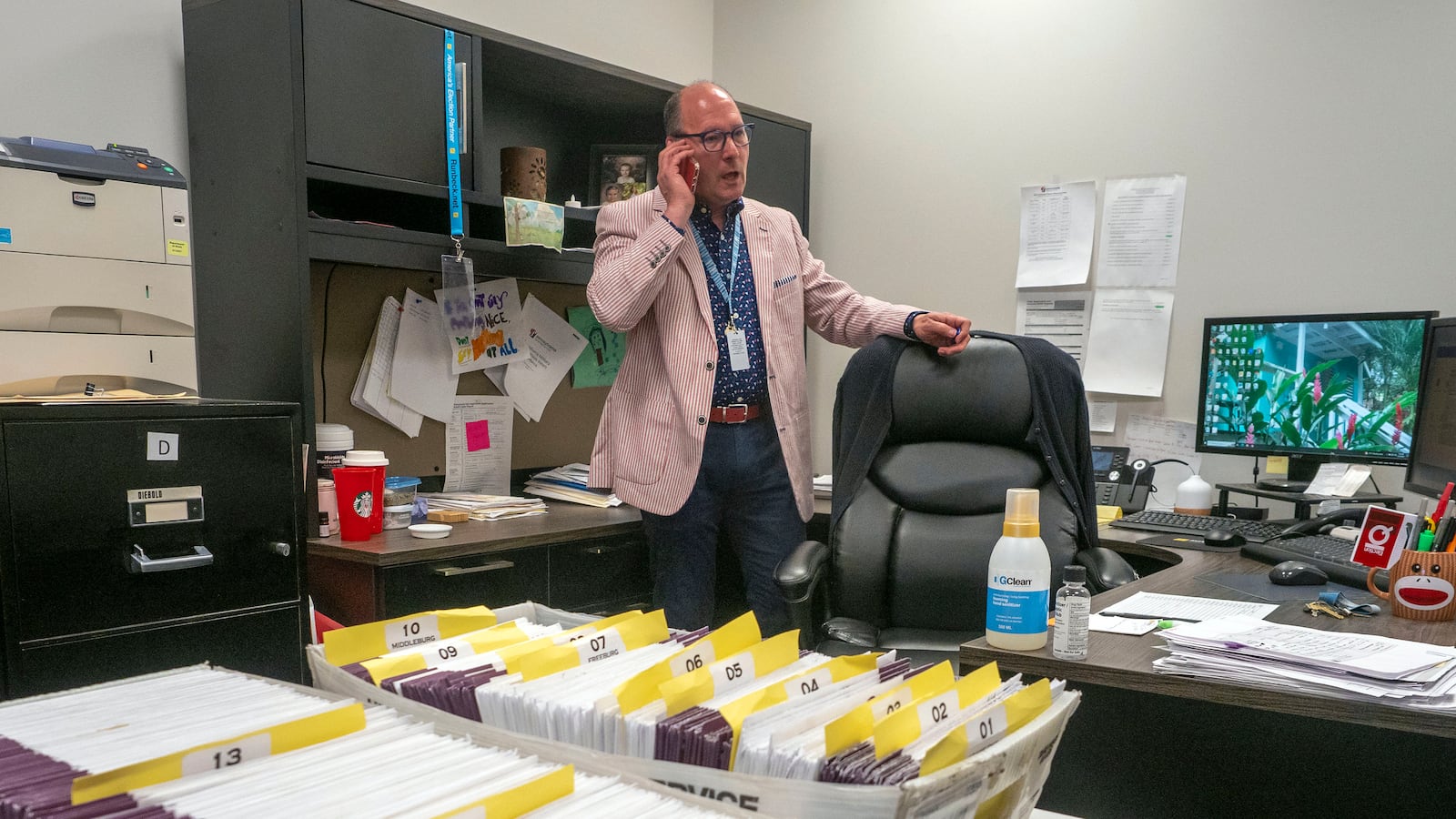

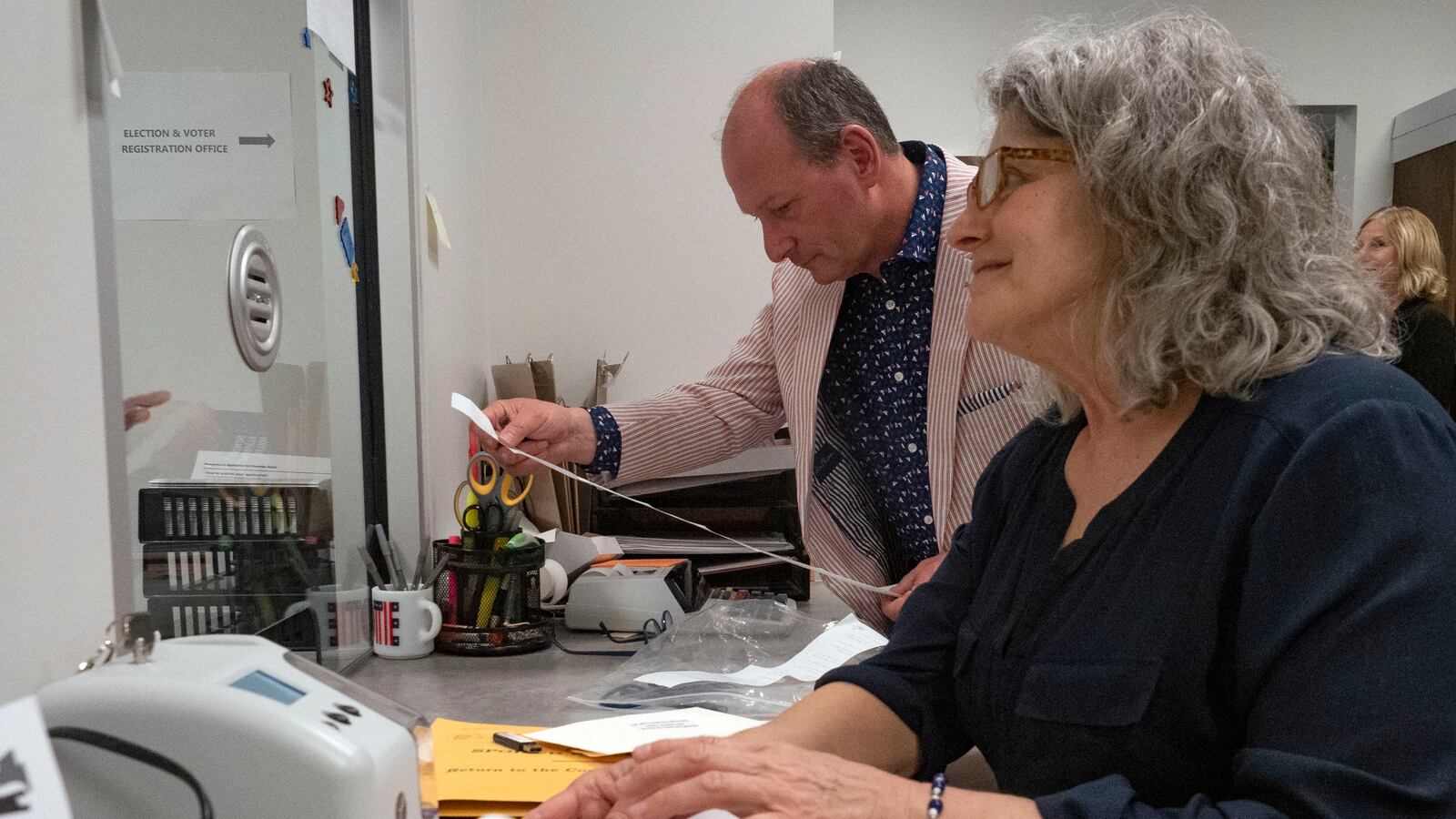

Sporting a red striped jacket, blue shirt, and red, white, and blue shoes, Rhoads cheerfully answered calls from voters, poll workers, and state officials throughout primary day, often ending one call on his cell phone and immediately starting another on his desk phone.

At 7:35 a.m., Rhoads answered a call on his desk phone from a voter asking what precinct they were registered for. At 7:37 a.m. an election office worker told him a polling place was missing some materials. At 7:39 a.m. Rhoads worked with a representative from his voting machine vendor to run a report. At 7:41 a.m. he took a call on his cell phone from another voter, who previously served as a judge of elections, asking how to use a new voting machine.

He took one call from a voter who was upset that they were registered with the wrong party and convinced there was a conspiracy to manipulate the county’s voter rolls. He calmly explained why that wasn’t true and offered to personally process her voter registration change after the primary.

When things are hectic, Rhoads tries to remind himself that the stakes are not as high as they could be. When he worked in the veterinary field, his days were heavily planned, as they are on election day, but emergencies often forced him to adjust.

“You pretty much had to, whatever you were doing, pivot to take care of the emergency,” he said. “I kind of approach things that way. This morning when I got that call (about Selinsgrove), it was more of a timing issue. It didn’t get me worked up, because no one died.”

One election down, and a big one coming up

Since being hired as director last May, Rhoads, like many new directors, has worked to prepare himself for the presidential election. He’s grateful he hasn’t had to do it alone.

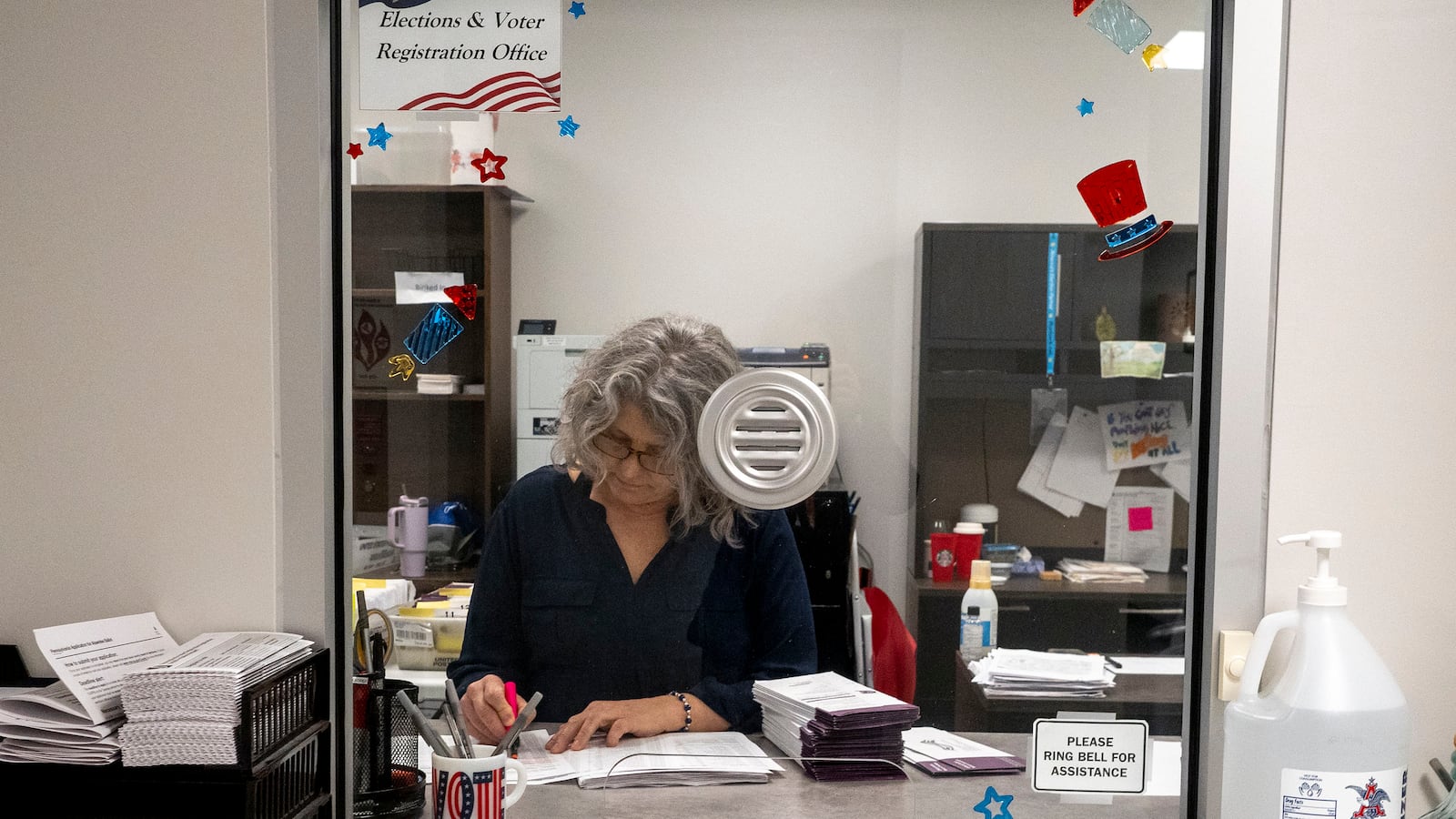

The county has turned to Pat Nace, its former longtime election director, as a mentor to Rhoads and the other new directors before him. She has also done consulting for some neighboring counties.

“They all have this expectation that elections are just two days a year and everything just comes together,” she said. “I set him straight right off the bat.”

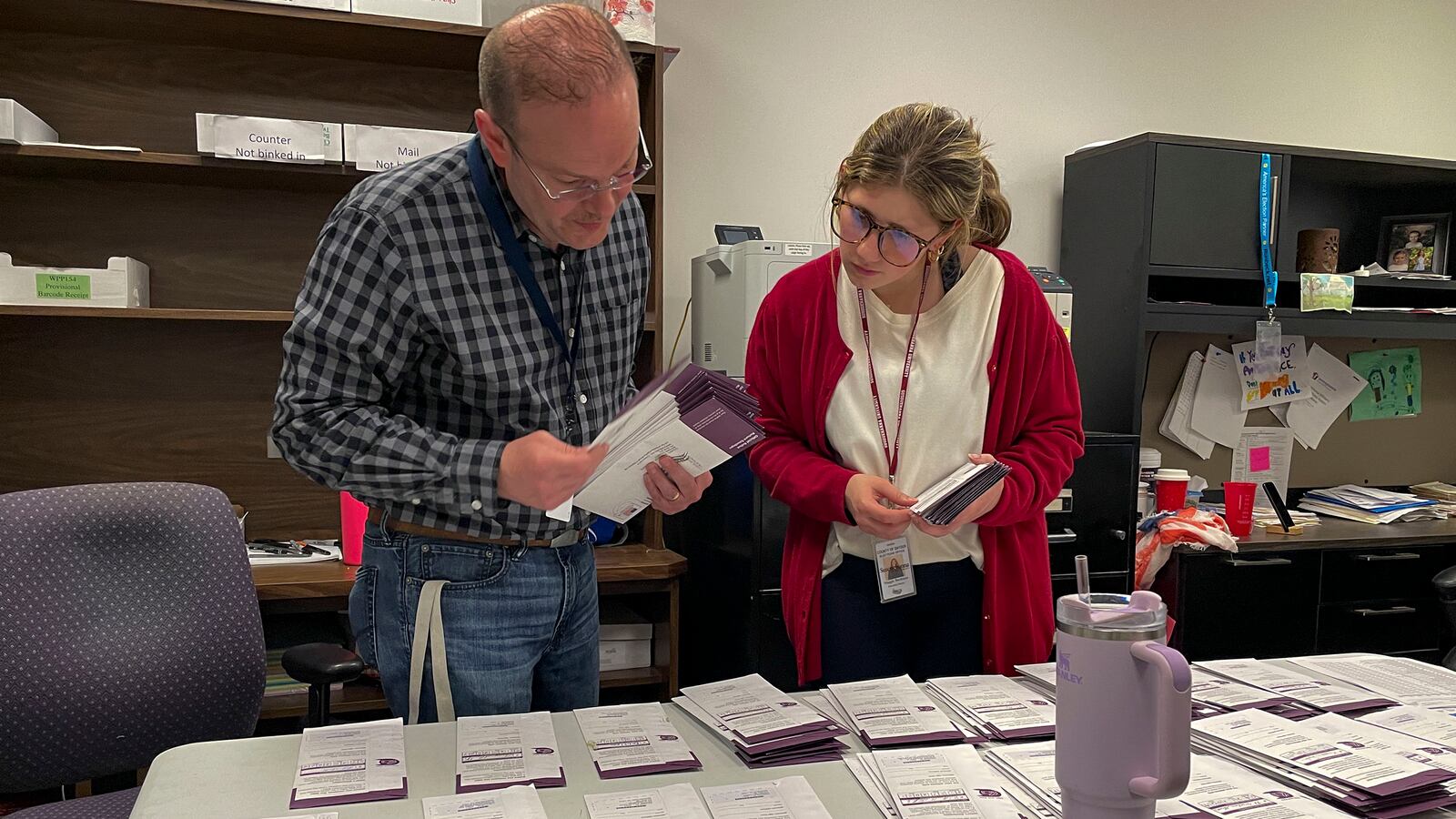

Nace prides herself on having maintained thorough records, and she has used those as a guide for new directors. She has coached Rhoads on the timeline of events and what he needs to do at each stage to make sure the election comes together in an organized fashion, as it did Tuesday.

“It’s a certain kind of person who is an election director,” she said. “You have to be organized, flexible, personable.”

And Rhoads “absolutely” has those qualities, she said.

The Pennsylvania Department of State has adopted a similar model. In 2023 it established a new training program for directors in response to the turnover.

The program is led by a former election director from Montgomery County, and hosted nearly two dozen sessions leading up to the primary. The department also created a calendar for directors that identifies pre- and post-election duties and deadlines for 2024, released a new version of its ballot review checklist for counties to use as a resource, and bolstered its county liaison program, among other initiatives.

Rhoads said these resources helped him gain his footing and reaffirm his understanding of how things work.

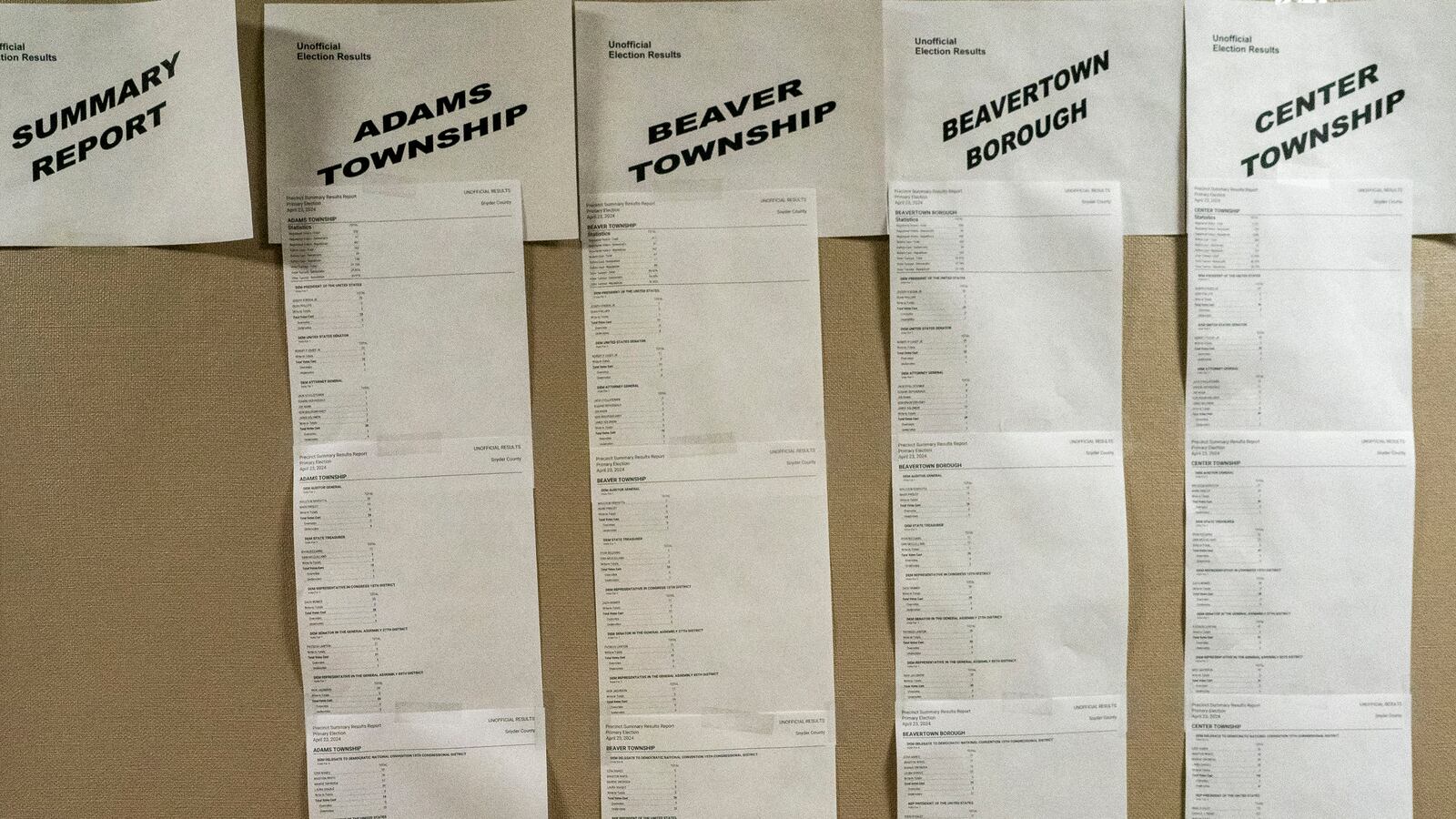

On primary day, as precincts started to return their results to the county courthouse around 8:30 p.m., it was clear Rhoads’ first presidential-year election had gone off without any major issues.

“I think we survived,” Rhoads told his staff before dismissing them for the night around 10:45. He credited the success to the team of roughly a dozen around him.

Ultimately, about 27% of the county’s voters had shown up to the polls, lower than the mid-30% range the county saw in the 2020 primary.

But November is expected to be much more contentious, and with much higher turnout. The 2020 election saw 76% of voters participate, the highest in nearly 30 years.

Asked if he was nervous about that election, Rhoads stayed characteristically optimistic.

“As I said to the one person, ‘Let me get through today and then I’ll start to worry about November,” Rhoads said at 11 p.m. after the rest of the staff had left. “I am not going to get worried and upset about something I don’t know. … We’ll deal with it as it comes.”

For this night, his only other concerns were going home, changing into some old clothes, and feeding the animals in the barn before getting some rest.

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org.