Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free newsletters here.

A vendor of voter registration management software is asking Texas counties that use its services to pay tens of thousands of dollars in surcharges to help the company stay afloat, or scramble for alternative ways to deal with sensitive voter information in a presidential election year.

The request has election administrators in some of the state’s largest counties consulting with county attorneys about their legal options. Others are trying to find the money to pay, worried about the stability of the vendor, California-based Votec Corp.

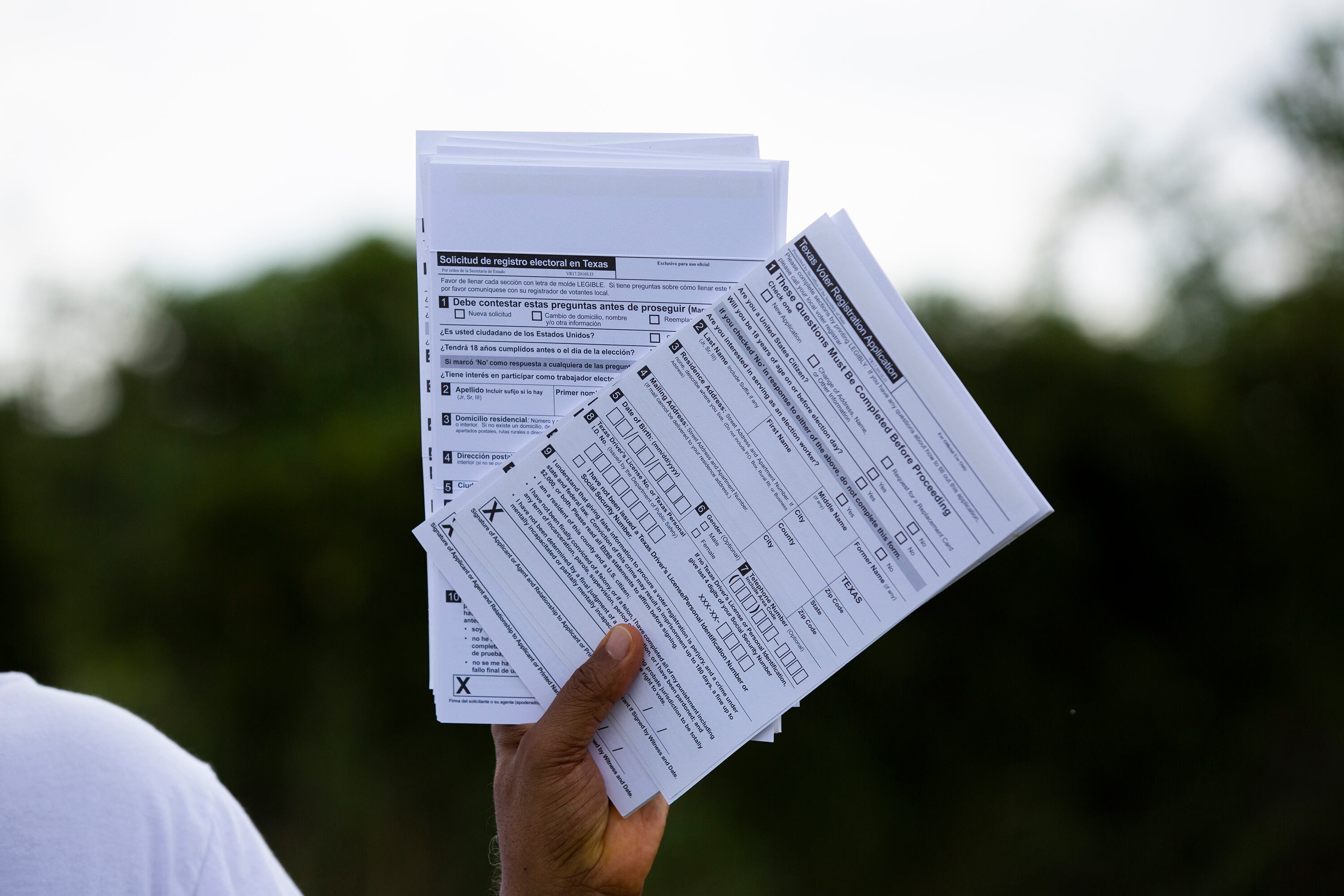

Election officials have few other options to store and manage the voter registration data of millions of voters across the state only months ahead of the May runoff election and November’s presidential election.

Election administrators in Harris, Dallas, Tarrant, Bexar, Collin, Williamson, and Hays counties all received the request for additional funds. Those counties represent a substantial percentage of the state’s 18 million registered voters.

In a message to counties on March 21 obtained by Votebeat, Votec CEO John Medcalf said some customers in Texas were “up to seven months late” making payments.

“These delays, plus mishandling by our payroll/health insurance company caused additional concern,” Medcalf wrote. He predicted that his company will be financially strong in 2025, based on the expected release of a new product, but said he must assess a “one-time” surcharge of 35% on Texas clients this year.

Thirty-two counties in Texas use Votec’s voter registration management software, dubbed Vemacs, and the company has done business in the state for more than two decades. It’s one of only three companies approved in Texas to manage voter registration data.

The software is also used by counties in Nevada and Illinois, but so far, Votec has asked only Texas counties to pay the surcharge.

In Dallas County, the election department received an invoice from Votec with a surcharge of $66,000. In Collin, the surcharge is more than $40,000, and in Hays County, it’s close to $20,000.

“This is a huge deal,” said Hays County Elections Administrator Jennifer Doinoff. “Any time that a vendor of one of the most important components of an election indicates financial distress, that’s scary.”

She said her county has yet to decide next steps, but said she can’t easily write a check for the surcharge Votec is seeking.

“We all have purchasing processes and procurement policies that we have to abide by,” Doinoff said.

Votec CEO says some counties have agreed to pay

Medcalf told Votebeat the surcharge is not “a last play before going out of business.” But he added that he didn’t yet know what steps he’d take if counties in Texas were unable or unwilling to pay the additional charges.

“We don’t want to see the counties harmed in any way,” he said. “We will enter discussions with them, ask how they can help while we’re helping them. I just have to assume we’ll all be adults in the room.” He said that for the most part, he’s gotten a “positive response” to the request, and that some counties have already agreed to pay.

Medcalf said a looming threat to Votec’s client base in Nevada, where 12 counties are customers, is not a major concern. Nevada is in the process of launching a new statewide voter registration system that counties will be required to use. Medcalf told Votebeat that the contracts with its Nevada customers are in effect until the end of this year, and said his company will be fine. He said the Nevada customers account for around $200,000 in revenue, or 5% of the company’s total.

“So we’ll miss them. But we expect much more than to compensate for that,” Medcalf said.

Votec has already lost two big customers in Nevada. Clark County, the state’s most populous, cut ties with Votec in 2022 after more than a decade. Medcalf said he had a falling out with the county’s registrar of voters at the time, but did not elaborate.

Nevada’s second-largest county, Washoe, also no longer has a contract with the company. Documents show Medcalf pushed back when Washoe signaled that it wanted to end the relationship. In a 2020 letter to the county’s registrar of voters, Medcalf wrote: “We can tell the registrar wants out of the contract. The registrar has terminated twice. The Registrar offered no reason for the first termination other than being nervous. To my unbelief, the purchasing and contracts manager upheld nervousness as a valid cause for contract termination.”

Texas’ own voter registration system has flaws

The Help America Vote Act, a federal law enacted in the early 2000s, requires states to develop and implement “a single, uniform, official, centralized, interactive computerized statewide voter registration list.” Exactly how that’s done varies by state.

Some states have one central database that connects to terminals in local jurisdictions. Other states gather and compile information from each local jurisdiction’s voter registration database. Texas uses a combination of those methods.

Most Texas counties enter their voter registration data directly in a statewide database called the Texas Election Administration Management system, or TEAM. The state developed the system in 2004, to meet the HAVA requirements.

But the system had flaws. Nearly half of Texas’s 254 counties reported it was slow and did not allow them to “perform their jobs effectively,” according to a 2007 audit by the State Auditor’s Office. More than a decade later, election officials say TEAM remains inconsistent. For example, they say TEAM can take anywhere from minutes to hours to produce a standard report using election data, such as a list of voters in the county who have requested an absentee ballot.

So dozens of counties, including the largest ones, maintain their own voter registration databases using private vendors, and sync their data daily with TEAM, as required by law. The Secretary of State’s Office approves vendors after ensuring their systems can exchange files with TEAM.

The information they help counties manage includes voters’ addresses, voting history, registration applications, images of signatures for verification, images of mail-ballot envelopes, and other personal data.

The state has been working on a revamped version of TEAM set to launch next year. Counties can migrate their data to the state system and start using it instead if they choose. The state already has most of the data, since counties that use private vendors are required to sync their information with TEAM.

The transition, however, would require training voter registration officials on how to use a new system.

Votec is part of a large industry of technology contractors and vendors that government entities use to manage key functions. Almost every state and federal government agency in the country relies on third-party vendors to manage and store important data.

Issues between vendors and government agencies aren’t uncommon, but election offices, which are chronically underfunded and have deadlines tied to statutes and elections, have little flexibility to get around disruptions, and fewer specialized vendors to choose from.

If a U.S. Department of Defense vendor seeks more money due to inflation, the federal government’s budget has more wiggle room, said Mitchell Brown, a political science professor at Auburn University in Alabama whose research focuses on the interplay between election departments and other organizations supporting elections. “We do not fund elections very well, and it puts additional pressure on the system. And this is why things like this become really critical,” Brown said.

Clarification April 4, 2024: The Secretary of State’s Office approves vendors of voter registration management software after ensuring they can exchange files with TEAM. A previous version of this story said such vendors go through an extensive certification process with the Secretary of State’s Office, but that more extensive certification process is used for voting machine vendors.

Natalia Contreras is a reporter for Votebeat covering election administration and voting access in partnership with the Texas Tribune. Contact Natalia at ncontreras@votebeat.org