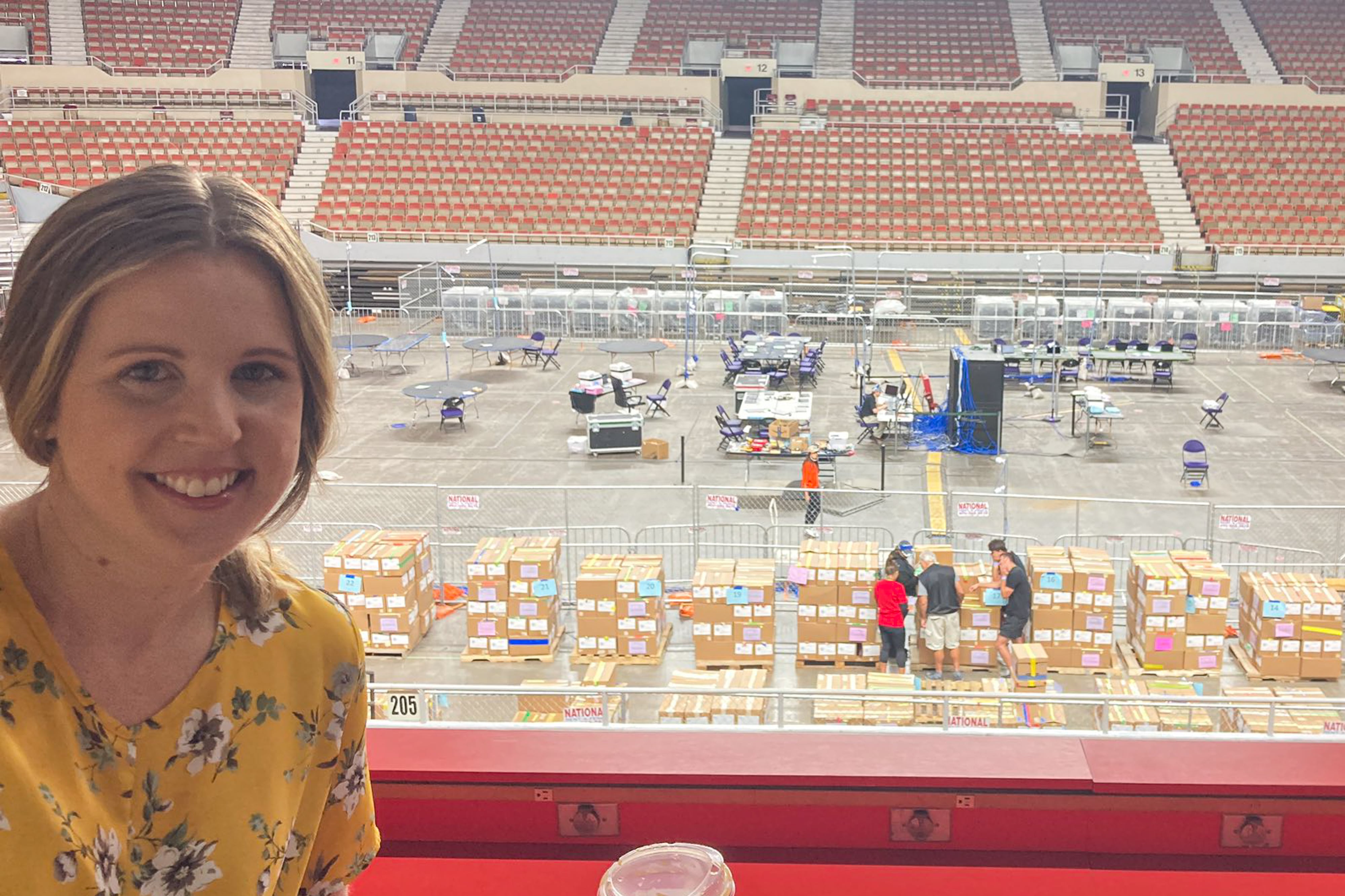

It wasn’t until I was inside Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Phoenix, pulling an oversize orange T-shirt over my blouse and looking out onto the coliseum floor as workers in colored T-shirts wandered along cages filled with boxes of ballots stacked as tall as our shoulders, that I fully understood the peculiar spot I was in.

I was the only journalist in the room. As a reporter for the Arizona Republic at the time, I had agreed to volunteer as an observer for the day in order to get inside, the only way reporters were permitted inside. I wasn’t allowed to have my phone, take notes, or record. There were no county or state election officials.

It was just me along with a tech guy from Florida who had been working with former President Donald Trump’s allies for months in an effort to prove that the 2020 election was stolen and dozens of people interested in helping him recount 2.1 million ballots and take apart voting machines.

I was still in shock that a judge allowed a cadre of Republican state senators access to our ballots and the million-dollar machines, and that the senators turned all that authority over to people without elections or auditing experience, and without any oversight.

In that moment, as I looked around, I realized it was completely up to me to let everyone outside the coliseum know what was happening, and to get it exactly right.

It was the very first day of the partisan review of Maricopa County’s 2020 election, a process that would ultimately sprawl for months longer than anyone predicted. I would spend my spring and summer in the coliseum stands, asking questions. For the election doubters, I asked about the way votes had initially been counted, the way vote-counting machines had been kept secure, and the way the county verified voters were eligible to cast ballots.

For those who believed the election was sound, I asked questions to uncover the partisan nature of the review, to figure out how Trump allies and supporters were involved, and to ensure our private voter information and ballots were being kept secure.

Along the way, I learned a lot about how voting works. I became fascinated by the complexity and fragility of our country’s election system. While I was able to help knock down the craziest of conspiracies about the 2020 election, the experience clued me into the myriad of ways that elections can and sometimes do go wrong and the myriad of ways local election officials try to prevent that from happening. It raised many questions in my mind about whether the election system is strong enough in all counties across the United States to block future attempts at election subversion.

This skepticism in me checks out. It’s inherent. Since childhood, I’ve been asking questions about why things happen the way they do. I didn’t just think the contrails behind a jet were cool — I wanted to know why they showed up in the sky. I had a hard time accepting religion, especially with the whole Noah’s Ark thing and Moses splitting the sea. I wrote a full essay in elementary school about why we dream. As a reporter, I’ve often been the contrarian in the room, pitching stories that challenge the popular narrative.

Covering elections and voting fits me. I’ve never been a political person, but growing up in an independent-minded state like Arizona taught me to appreciate American freedoms and representative government. As a journalist, I’m most proud of the times I have been able to hold government institutions and elected officials accountable, no matter which side of the aisle they were on. In Phoenix, I wrote about an independent mayoral candidate’s unexplainable campaign finances. Covering the small city of El Mirage, Arizona, I found that the city had illegally issued hundreds of speeding tickets and hadn’t paid all drivers back. In the Democratic city of Frederick, Maryland, I pushed city officials to explain why they didn’t properly vet a government contractor who left dozens of homeowners high and dry after promising to build the first net-zero neighborhood in the country.

I see elections as the government role with the highest stakes. That means there are plenty of people to hold accountable for ensuring that eligible voters can easily vote, and that ineligible voters can’t.

Covering the fallout of the 2020 election has been the most important work I’ve done in my career. And the work continues.

Arizonans remain heavily concerned about elections at the same time local news outlets may lack the resources to cover them year-round. The coverage ebbs and flows with the election cycles and the need to cover other news.

That’s why Votebeat exists.

I want to be there for voters, and especially Arizonans, full-time, to answer their questions about our elections and voting rights. I want voters to be prepared to dismiss the next fake conspiracy, whether it emerges this year or in 2024. I want to give local election officials a voice to tell voters what they do year-round to protect the sanctity and secrecy of our votes.

Voters of all stripes, for different reasons, are viewing elections through a prism of fear and worry. I want to try to unite the community through the truth. Even if it means that sometimes I’ll be the only one in the room.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.