When the Cochise County supervisors sat down to talk about elections in August, they were well aware of what happened the last time the county’s leaders tried to test the limits of state law.

The rural Arizona county on the Mexican border is where, during the 2022 midterm election, two Republicans on the Board of Supervisors devised a plan to ditch the machines used for elections and instead hand-count votes, before a judge foiled their plan. They then delayed the vote to finalize the county’s results until the same judge ordered them to certify them.

Supervisor Tom Crosby, who was re-elected last year, is awaiting a criminal trial on charges related to his actions during that election. And the county’s two new supervisors, also both Republicans, know his story well, and have been warned by the secretary of state about the election rules they must follow.

Nonetheless, at an Aug. 5 meeting, Supervisor Frank Antenori said the board needs to test the state’s laws once again, to see if supervisors really are obligated to use machines to tally votes, and whether they really have a non-discretionary duty to certify results. And Supervisor Kathleen Gomez said that if she had been in office in 2024, she wouldn’t have certified the county’s election results because of problems that occurred while counting ballots.

“I think we have to put this back in play in the courts,” Antenori said about supervisors’ duty to certify elections. “We have to make a case to go fight this again, or get the Legislature to change the statute.”

With another midterm election nearing, the supervisors are all but vowing to test the boundaries of state election laws that are meant to ensure accurate, secure, and timely election results. Hand-counting ballots has been proven in multiple studies and trials to be less accurate and take more time. And certification deadlines, if breached, could disrupt the transfer of power at all levels of government, from local to federal offices.

The false claims of election fraud have slowed in Arizona since Donald Trump won the presidential election last year, but the conversation among the supervisors last month, and several others earlier this year, are an indication of how Trump’s prior claims continue to influence how Arizona’s elections are perceived and run, and how they could lead to future challenges to results in 2026 and beyond.

Secretary of State Adrian Fontes, a Democrat, was invited to present at the supervisors’ August meeting, but didn’t go after seeing he was being asked to present alongside someone who had encouraged the supervisors in 2022 to block the certification of the midterm results, according to documents obtained by Votebeat through a public records request.

After the meeting, his communications director, Aaron Thacker, told Votebeat that there is no debate about what the law requires the supervisors to do. And he said that the repeated attempts to question certified election systems in Arizona, particularly in smaller counties, “do more to undermine public confidence than to address any real issue.”

Hearing 2022 claims repeated at supervisors meeting

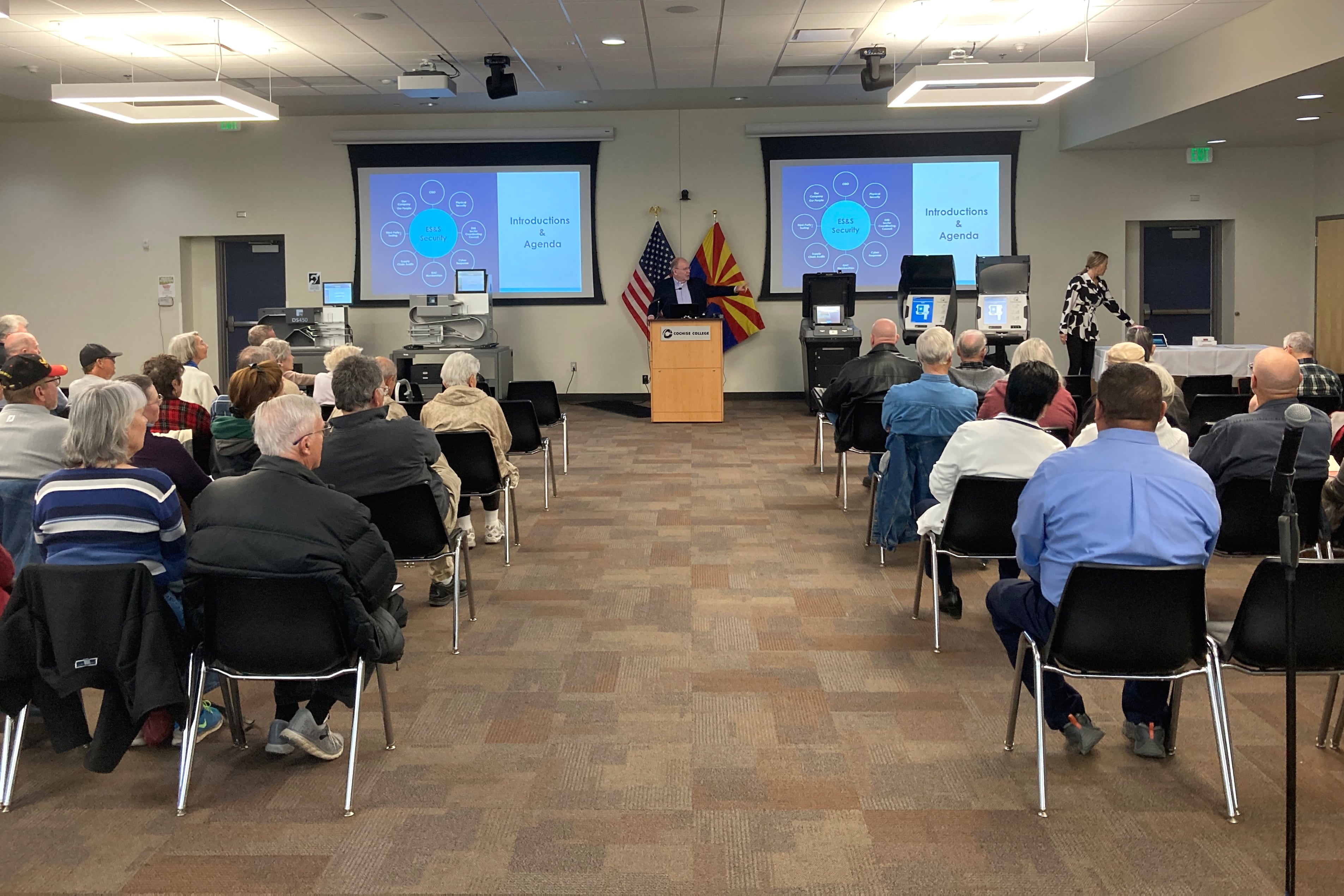

The goal of the August meeting, Antenori wrote in his invitation to Fontes, was to “ensure transparency, build voter confidence, and evaluate the proper processes for verifying machine integrity.”

The other invited speaker was Paul Rice, a Phoenix resident with no formal experience in elections but who was previously involved in a court case challenging the state’s use of the machines that tally votes, including ballot-marking devices and tabulators. Rice has been lobbying Cochise supervisors to get rid of the machines since 2022.

His major claim is that the laboratories that certified the state’s voting systems in the leadup to the 2022 election were not properly accredited. That claim is part of what Crosby and former Supervisor Peggy Judd said prompted their hesitation over certification.

At the time, then-Secretary of State Katie Hobbs sent the supervisors an explanation from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission about how the labs were properly accredited. But supervisors still delayed their vote, demanding to hear from Rice and Hobbs in person. That never happened, and the judge forced them to certify before the state’s deadline.

Rice accepted the invitation to the August meeting and talked for about 45 minutes, without other public comment allowed or any rebuttal from the County Attorney’s Office. He repeated his claim about the lab accreditation, and said he didn’t believe the county had to use the machines. He also said the law on certification wasn’t clear.

Rice repeated an argument that Crosby has attempted to make in his criminal case: that state law mandates that supervisors “canvass” results, but does mandate that they “certify” them. He said he believes canvassing just means reviewing the vote totals — not signing off on them.

Thacker, Fontes’ spokesman, disputed Rice’s claims in a response to Votebeat. He pointed to a sentence in state law that says electronic tabulation equipment must be used to count ballots. And he said that courts have made it clear that the only authorized hand count under state law is a post-election audit, which examines votes cast on a limited number of ballots.

On canvassing vs. certifying, Thacker said Rice’s claim is semantic and there is no legitimate debate about it.

“In Arizona law, the canvass is the process by which the election results are reviewed and officially confirmed — it is the act of certification,” Thacker wrote in an email.

Ali Morse, a Cochise County resident who helped lead a response in opposition to the supervisors’ 2022 actions, said she experienced déjà vu watching Rice’s presentation.

“The Board’s work session, in fact, appeared to be an attempt to amplify Supervisor Crosby’s dubious justification for unlawfully refusing to certify/canvass our 2022 general election which catapulted Crosby into his current mess of legal and financial problems,” Morse wrote in a letter to the editor published in a local paper, The Herald Review.

Jenny Guzman, program director of Common Cause Arizona said the misinformation given at the meeting is dangerous.

“It’s really important for people in government, especially county supervisors and people in other elected offices, to really remember that sometimes they are the only line of communication to voters,” Guzman said. “They need to make sure they aren’t providing any sort of information that isn’t accurate.”

New supervisors preparing to hand count ballots

The conversation was the latest in a long string of attempts by the new supervisors to signal to constituents who are concerned about election integrity that they are listening.

In a February conversation about elections, the supervisors said they eventually want to get to a place where they can hand count ballots. That means first going back to precinct-style voting, where voters can vote only in their precinct, rather than anywhere in the county, they said.

And Antenori said that he would like to make the plan ahead of an election, so that supervisors can get the legal battle with the state out of the way beforehand. Otherwise, he said, “I think we are fighting with two feet in the grave.”

After that discussion, Fontes sent the supervisors a letter warning them against it, saying the only hand count allowed is the statutorily prescribed review of ballots, which specifies how many ballots should be reviewed. “Manual tabulation of ballots outside of this prescribed sample audit, whether in addition to, or in lieu of using electronic tabulation equipment, raises many logistical as well as legal concerns,” he wrote.

But again in April, even as supervisors voted 2-1 to spend $308,000 on two new high-speed tabulation machines, they said they eventually want to get rid of them. At that meeting, Antenori repeated his desire to test the law on ballot tabulation, in civil court, before an election.

Gomez said at the time that she would like to get rid of machines to count votes, but she believes state law requires the county to use them. She said the same thing in a recent interview with Votebeat. Also, machine malfunctions during the 2024 elections, which didn’t affect the results but did slow down the counting process considerably, concerned her, she said, and she would have had trouble certifying that election.

At the April meeting, she asked the public to have patience while the supervisors figured it out. If they proceed now with the law as it is, she said, “they will come after us and they will put us in jail the minute we say we have no machines.”

It was one of many allusions supervisors made to the charges against Crosby, who has pleaded not guilty to interference with an election officer and conspiracy. As he awaits trial, Crosby has demanded the county cover about $300,000 in legal fees.

The supervisors had attempted to pass that claim on to the insurance pool that represents county governments in the state. But the pool denied that claim last month. A pool attorney said in an Aug. 11 letter that its agreement with the county excludes coverage of claims arising out of any “dishonest, fraudulent, criminal, malicious, deliberate or intended WRONGFUL ACT.”

The pool also reserves the right to deny a claim when “it does not involve accidental and fortuitous circumstances,” the lawyer wrote.

Last week, the supervisors met in private to discuss what to do now.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.