Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for our free weekly newsletter to get the latest.

Maricopa County Recorder Justin Heap said his office rejected 5,903 mailed-in ballots in the Nov. 4 election over mismatched signatures — or roughly 838 for every 100,000 ballots cast, more than double the rate of the 2024 general election.

Heap, a Republican who took office in January after campaigning on a platform of election integrity, said he put new practices in place to verify signatures on mail-in ballots that sped up the process, made it more secure, and will boost public trust in elections.

But Heap’s report on Wednesday, which came during the canvass of the countywide jurisdictional election, troubled three of the five members of the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, who questioned him about the results.

Board Chairman Tom Galvin, a Republican, emphasized the disparity in rejection rates between this year’s election and the 2024 presidential election, when officials rejected 7,220 ballots for bad signatures, or about 396 for every 100,000 cast.

“If you increase the number of signatures being rejected, do you think that increases the trust in elections?” Galvin asked Heap during the canvass.

He said he’s concerned that if the rejection rate continues to climb, candidates in the 2026 election may file suit to demand that rejected ballots be counted.

Heap said he’s trying to increase trust through bipartisan verification, transparency and multiple security checks.

Arizona’s signature verification process

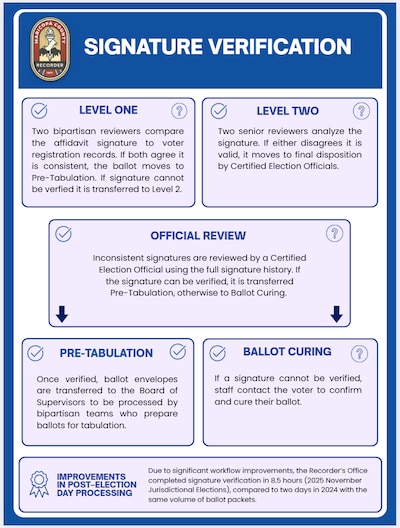

In Arizona, voters who mail in their ballots sign an affidavit on the envelope, and it is the job of county recorders to verify the signatures by comparing them with sample signatures on file.

Arizona law requires counties to notify voters when they flag an inconsistent or missing signature, and the law gives voters until three days after Election Day for jurisdictional elections to call, text, or visit county offices to confirm that the signature belongs to them, a process called curing. If the voter does not cure the ballot by the deadline, it is rejected.

A 2024 Votebeat investigation in partnership with the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting found that the number of ballots rejected for questionable signatures in Maricopa County tripled between the 2020 presidential election and the 2022 midterms under Heap’s predecessor, Republican Stephen Richer.

Richer implemented a stricter signature verification process in response to false claims of voter fraud and pressure from his own party.

The investigation found that flaws in the county’s signature verification process could lead to disenfranchisement that disproportionately affected voters who are younger, newly registered, or unaffiliated with a political party. Voters whose signatures change with age and voters with disabilities also tended to be flagged for questionable signatures.

Arizona has had elections decided by a few hundred votes in recent years, so even a small number of rejected ballots could affect the outcome.

Heap says his approach sped up reviews

The Nov. 4 election included 30 jurisdictions and 48 contests and one countywide election to decide a tax increase for a public-health district. All 2.7 million registered voters in the county received a ballot in the mail.

Heap and his staff said the fact that it was all done by mail may have contributed to the high rejection rate, because it brought out voters who haven’t voted by mail in several cycles or even decades and who have only one signature on file to compare.

“I think it’s the nature of this type of election compared to a regular election,” Heap said.

Heap, who was a critic of how Maricopa County administered its elections before he took office, said his new signature verification process starts with bipartisan teams that examine a signature simultaneously. A questionable signature will go to a supervisor to determine if it needs to go to a third level of examination.

Under the previous administration, he said, one person reviewed a batch of 250 to 500 ballots and then rechecked their work before sending questionable signatures to a supervisor to determine if the ballot needed to be cured.

He said that process took far too long, especially when the county was buried with “late early” ballots, or ballots that voters on the Early Voting List would drop off on Election Day at a designated site rather than sending in the mail.

Heap said at the canvass that his office was able to get through the late-early ballots in 8.5 hours, compared with 48 hours in last year’s primary. Jennifer Liewer, a deputy elections director for Maricopa County, later told Votebeat that it took the county a day to handle the 2024 primary ballots.

“In the end, signatures either match or they don’t,” Heap said.

Tension between Heap and supervisors

Heap shares election duties with the Board of Supervisors, and they’re locked in a fierce legal battle over the division of election responsibilities. The county recorder handles campaign finance, voter registration, and early voting.

Supervisor Kate Brophy McGee, a Republican, said at the canvass that she would like to know more about the rejected ballots, such as which parts of the county they are from, to identify whether there was a problem that led to so many rejected ballots.

“It’s my belief that people don’t fill out their ballots and sign it — whether it’s on a steering wheel, their lap or whatever — with the idea of mailing it in and not having it be counted,” Brophy McGee said.

Galvin said Thursday that he understands Heap’s intent and that the supervisors’ board has no authority to force him to handle the process differently, but he said the recorder should consider the feedback.

“The increased rate was staring us in the face,” Galvin said. “How could we ignore it?”

Batch of ballots misplaced

County staff also briefed supervisors on a batch of ballots that were misplaced and found on the last day voters could cure them.

Elections Director Scott Jarrett, who works for the supervisors board, said election workers at a Glendale voting location took two sealed bins containing 2,288 ballots, in their envelopes, and placed them in a dropbox to wheel them to a truck for transport to an elections warehouse.

The driver did not tell anyone at the elections warehouse that the bins were in the box, and they weren’t discovered until a few hours before the cure deadline on Nov. 7. Liewer later told Votebeat it was eight hours before.

Jarrett said the chain of custody on the ballots was intact.

Workers with the Recorder’s Office worked frantically to process the ballots and deal with the ones that needed to be cured. Staff contacted the voters whose signatures were questionable every three hours, said Ray Valenzuela, who is in charge of early voting for the Recorder’s Office.

All but 16 of the ballots were cured and counted. Jarrett said the county is now looking into real-time tracking.

Correction, Nov. 20: An earlier version of this story misstated the time limit under state law for Arizona voters to cure their ballots. It is three days after Election Day for jurisdictional elections, and five days for federal elections. This story has also been updated to include comments from Jennifer Liewer, a Maricopa County deputy elections director, and clarify that both Heap and Liewer were referring to the 2024 primary ballots.

Contact Votebeat at az.tips@votebeat.org.