Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s free weekly newsletter. Sign up to get future editions, including the latest reporting from Votebeat bureaus and curated news from other publications, delivered to your inbox every Saturday.

Virginia election officials continue to face a major challenge keeping their voter rolls up to date after the state withdrew last year from the data-sharing coalition ERIC, the Electronic Registration Information Center. As Votebeat recently reported, the state has since spent tens of thousands of dollars to get access to just a sliver of data it used to get through its ERIC membership.

For a brief moment, it looked like the state might have found part of a solution — but one that apparently is now a casualty of politics and a misunderstanding.

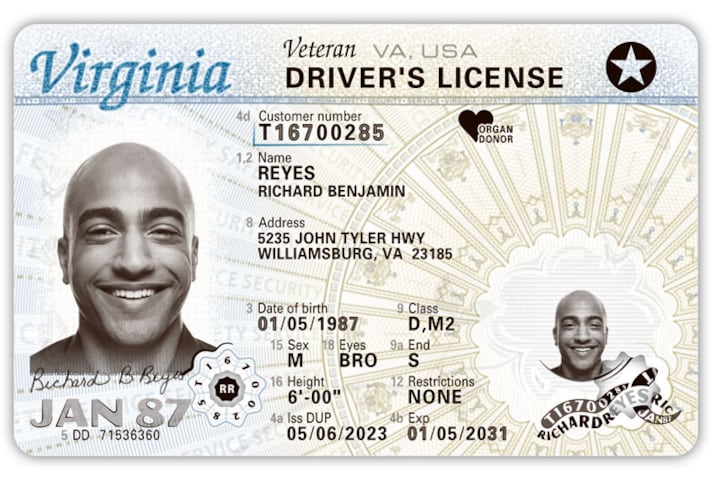

A pair of bills, HB 565 and SB 315, would have allowed the state to automatically update a person’s voter registration if they updated their drivers license address with the DMV. It’s a simple type of change and one that has worked in other states.

Trey Grayson, former Kentucky Secretary of State and chair of the nonpartisan Secure Elections Project, was advocating on behalf of the bill. “This would be huge for Virginia,” Grayson told me late the previous week, before the bills went kaput. He said it’s particularly important now that the state has abandoned its primary sources of voter roll data. “In a lot of ways, this is better than ERIC — it requires nothing of the voter and keeps the rolls up to date seamlessly.”

Right now, when a Virginia voter updates their information with the DMV, they are asked to affirm that they also want to update their voter registration. A lot of people just hit no, not realizing their registration is out of date or just wanting to get the heck off of a DMV website. This bill, instead, allows the system to automatically detect whether a home address has been changed, and then forward that change to the state elections office, which will verify the information matches and update the record without any additional steps from the voter.

It’s not rocket science, and it’s also not that difficult to implement. Other states that have put similar programs in place have reported great success. While Colorado, for example, wired up the program as part of a larger launch of automatic voter registration, Kentucky implemented a program without one. Rather than shifting how people register to vote or their eligibility, this approach would allow two state agencies to more freely share information.

One of the biggest drawbacks of the bill was evidently a misunderstanding of what it would actually do — the word “automatic” led lawmakers and advocates to assume the bills proposed a form of automatic voter registration, a more ambitious system that registers new voters if they engage with the DMV for any reason and are eligible to be registered.

“I’ve always been frustrated by the naming of this reform,” Grayson told me.

Critics also falsely assume, Grayson says, that any interaction with the DMV, like changing the address on a vehicle registration, would update the voter registration, which Grayson’s group was trying to debunk.

Tony Franquiz, a spokesman for the Secure Elections Project, also said Republican lawmakers had been “provided with faulty info on cost and the implementation” of the bill. While estimates suggested this bill would have saved money, “diverging opinions” still existed on the “complexity and cost of implementation.”

The misinformation surrounding the legislation was probably its undoing — as was a puzzling strategy by its Democratic sponsors. Ahead of a planned vote on the measure, both sponsors of the legislation opted to table it “in exchange for a seat at the table during the interim to discuss the bill and open up a discussion on a broader automatic voter registration package,” said Franquiz. “The bill is effectively dead for this session.”

Though, he said, there is talk of a potential retreat this summer for lawmakers to discuss a AVR package.

So now, a straightforward bill that was mistaken as a form of AVR, and hindered because of it, could now get rolled into an actual AVR bill. The right flank of the GOP — as local opposition to even the word “automatic” might suggest — have been agitating against AVR across the country for quite some time. Opposition to it is a favorite talking point of right-wing think tanks and activist groups, like the Heritage Foundation and True the Vote. Republicans in Pennsylvania are, right now, suing the governor over the issue.

Democrats, who control Virginia’s legislature, may be able to pass such a bill on a party-line vote, but it’s unlikely to fly with Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin. I’ve reached out to Sen. Saddam Salim, who sponsored the legislation and agreed to pull it, with questions but haven’t heard back. We’ll update this on Votebeat’s website if I do.

“The reality is that it is really hard to do bipartisan election legislation right now,” Grayson told me in a text message after the bill’s demise. “Hopefully this bill starts a conversation in Virginia about how to make voter rolls more accurate and that conversation will yield some fruit in a future legislative session.”

Jessica Huseman is Votebeat’s editorial director and is based in Dallas. Contact Jessica at jhuseman@votebeat.org.