Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Pennsylvania’s free newsletter here.

When Pennsylvania voters head to the polls this fall, more of them than ever will be using iPad-style tablet computers to sign in rather than paper.

Over half of Pennsylvania’s counties are now using these electronic pollbooks, with rapid growth fueled in part by an allocation of state money that started in 2022.

Election officials and advocates say e-pollbooks make voting quicker and more efficient, while helping election officials keep more accurate records. Plus, they argue, if the state ever institutes in-person early voting, as many states have done, they will be essential for making sure polling sites and workers have the most current information.

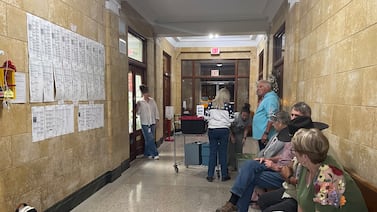

E-pollbooks are digital versions of the printed voter lists poll workers use to check in voters at precincts on Election Day. They speed up check-in by enabling election workers to look up voters’ names quickly, rather than having to thumb through the physical books to find the right page while the line of waiting voters keeps growing, said Megan Maier, deputy director of research and partnerships at Verified Voting.

They typically run on a laptop, tablet computer, or similar device, using specialized software. Most pollbooks used in Pennsylvania run on Apple iPads.

According to data from Verified Voting, 84% of voters across the country will check in with the help of an e-pollbook this November, up from less than 50% during the 2016 presidential election.

In Pennsylvania, the growth has been even steeper.

In 2016, just four counties were using e-pollbooks, according to Verified Voting, and in 2020, it was 10 counties. Now, according to a map from the Pennsylvania Department of State, 33 of the commonwealth’s 67 counties are using them, and at least one more is doing a pilot program this fall.

Mercer County purchased e-pollbooks for its 91 precincts in August, and will use them in next month’s election. Thad Hall, the county’s election director, agreed they help check voters in more quickly and make it easier for workers to resolve issues such as voters being in the wrong location.

But the most important benefit, he said, is that it will make it easier and faster to conduct a critical post-election check known as reconciliation, when counties check the number of ballots they received against the number of voters recorded as having voted, to make sure that the numbers line up.

In counties that use paper pollbooks, this process involves poll workers using the “numbered list” — essentially a manual running tally — of all the voters who come into the precinct, and double-checking it against the number of ballots that are voted in the precinct.

This can introduce human error, Hall said, because poll workers sometimes make mistakes recording voters on the numbered list.

The e-pollbooks, by contrast, automatically keep the tally of all the voters who cast a ballot at a given polling place. And once the polls close, election workers can simply upload all the precinct tallies to the state’s election management system.

Equipment is expensive, but new legislation could help

Jerry Feaser, a former Dauphin County elections director who now works for e-pollbook vendor Knowink, said the surge in e-pollbook use in the state is due in large part to Act 88, a 2022 law that distributed $45 million each year to Pennsylvania counties for election administration — one of the state’s largest-ever investments for that purpose.

Some counties used those funds to purchase equipment while others used them to offset other election costs, freeing up county dollars for big purchases.

Hall said Mercer County couldn’t have afforded the e-pollbooks without Act 88. Mercer County purchased the physical equipment with county money, but Act 88 funds help cover the software and ongoing support costs.

“The Act 88 money is critical for us doing this over time, being able to pay for the recurring cost,” he said.

Even with the state money, the cost can be a barrier.

The Knowink Poll Pad, the most widely used device in the state, costs $1,750 per unit, according to Feaser, and additional software and services can increase that price.

Hall said that in total, Mercer County paid roughly $200,000. For Lancaster County, which currently does not have e-pollbooks, it would cost more than $400,000 to put them in all 240 precincts.

A bill before the state Senate could provide more funding for other counties to purchase the devices while also creating new requirements for them.

The bill, sponsored by state House Speaker Joanna McClinton (D., Philadelphia), cleared that chamber earlier this year, and would provide $60 million for the purchase or lease of e-pollbooks and election infrastructure equipment.

The bill would also provide a clear definition of what an e-pollbook is and what standards it must meet, something that doesn’t exist in state law now. The secretary of the commonwealth currently regulates and certifies them under other authorities granted in the election code, but McClinton’s bill would codify standards.

Regulation and early voting

E-pollbooks are also practically a necessity for another one of the speaker’s priorities: early voting.

Paper pollbooks need to be printed and delivered to polling sites ahead of Election Day. McClinton’s bill would allow early voting up until the Sunday before Election Day, leaving little time before the Tuesday election to print updated pollbooks that reflect all the voters in the precinct who already cast ballots early.

But the bill is stalled in the Republican-controlled state Senate, where GOP lawmakers have repeatedly said they will not advance election legislation without an expanded voter ID requirement, which McClinton’s bill lacks.

E-pollbooks have run into some problems. Philadelphia experimented with Knowink e-pollbooks in 2019, but ultimately decided to scrap the contract just weeks before Election Day due to difficulties connecting the devices to printers and “inadequate election night reporting,” The Philadelphia Inquirer reported at the time. Philadelphia ultimately moved forward with a different vendor, Election Systems & Software, in 2023.

Maier, from Verified Voting, also said that while e-pollbooks typically speed up the voter check-in process, they can cause issues if they haven’t been synced with the most up-to-date voter list.

But in general, the new technology has been popular. Feaser said that after his workers tested e-pollbooks in Dauphin County in 2019, they were reluctant to give them up.

“They said, ‘If you try to take this away from us, we will charge the courthouse with torches and pitchforks,’” Feaser recalled.

Carter Walker is a reporter for Votebeat in partnership with Spotlight PA. Contact Carter at cwalker@votebeat.org.