Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization reporting on voting access and election administration across the U.S. Sign up for Votebeat Texas’ free newsletter here.

Some county election officials across Texas say the number of people voting by mail has dropped since 2020, but they’re not sure why.

New research suggests that the recent overhaul of state election laws could explain some of the drop.

A study from the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law School looked at Texas voters whose mail ballots or applications to vote by mail were rejected in the 2022 primary, after the state enacted new identification requirements for mail ballots, among other changes. Many of those voters, the study found, appear to have switched to other voting methods or, in some cases, stopped voting.

The study found that 30,000 voters in that primary — or 1 out of 7 voters who started the process to vote by mail — had either their application or ballot rejected, and that “roughly 90% of these individuals did not find another way to participate in the 2022 primary.”

The authors said their findings show the potentially lasting effects of restrictive voting policies on even the most engaged voters.

About 85% of voters whose applications or ballots were rejected had voted in general elections in 2016, 2018, and 2020, said co-author Kevin Morris, a senior research fellow and voting policy scholar with the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program.

“This is a group of people that are super highly engaged in the political process,” Morris told Votebeat. “They have a long history and habit of voting, so to see these effects among them is a big deal.”

The peer-reviewed study, co-authored with political scientists from Barnard College and Tennessee State University, is set to be published later this year in the Journal of Politics and was shared with Votebeat.

After Senate Bill 1, more rejections, less participation

Texas has long had strict limits on voting by mail, allowing it only for certain groups of people, including voters age 65 and up and people with disabilities. Voters who are eligible must apply to use mail ballots each year. If their application is accepted for a primary election, they’ll automatically get a mail ballot for that year’s general election as well. If the application is rejected, they have to reapply.

In 2021, state lawmakers tightened the restrictions as part of an election law overhaul called Senate Bill 1. The legislation required voters to write their driver’s license or personal identification number, or the last four digits of their Social Security number, on the mail ballot application or mail ballot envelope — whichever number they originally used to register. If the ID number was missing or didn’t match the number on file, the application or ballot could be rejected.

The March 2022 primary, the first statewide election after the legislation took effect, saw a dramatic increase in rejection rates: 12,000 absentee ballot applications and more than 24,000 mail ballots were rejected, amounting to a 12% rejection rate statewide, far higher than in previous years. In the 2020 presidential election, by comparison, the rejection rate was 1%.

Mail-voting applications and ballots of Asian, Latino, and Black Texans were rejected at much higher rates than those of white voters after the ID requirement was added, according to an earlier study by the Brennan Center.

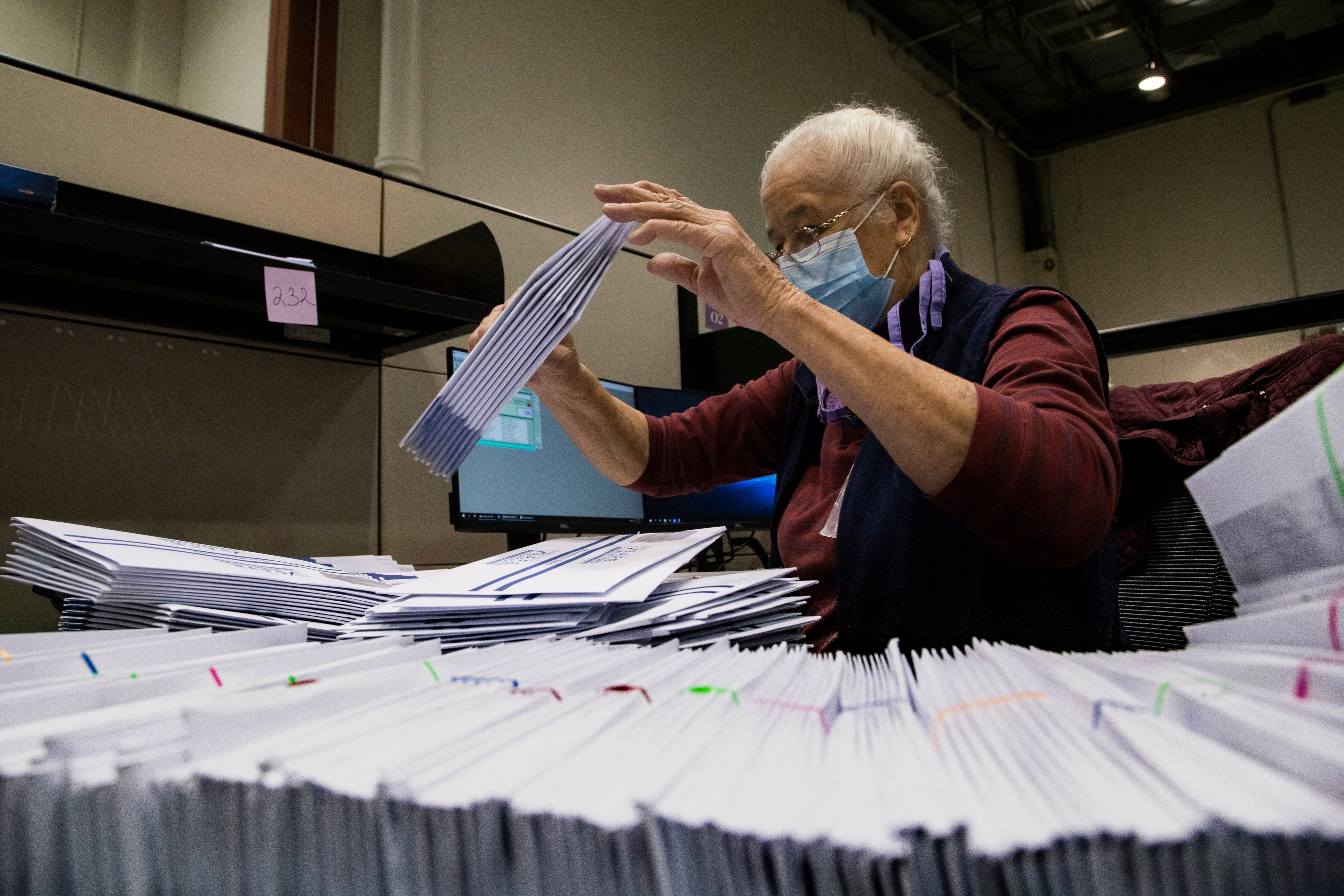

For the more recent study, researchers obtained individual-level data on mail-voting ballot applications and mail ballots in the 2022 Texas primary from litigation documents and public-records requests to the Texas Secretary of State. They looked at the demographics and the voting history of the roughly 215,000 Texans who requested a mail ballot for that primary, and drilled down to the 30,000 voters who had either their application or ballot rejected.

More than 3,000 voters whose mail-voting applications were rejected voted in person instead in the 2022 primary.

Out of the more than 18,000 voters whose mail ballots were rejected, only 344 voted in person. The others did not ultimately vote in the primary.

The study said the rejections increased what it called the “cost of voting,” because voters had to “try to sort out why their mail ballot did not arrive, re-apply for an absentee ballot, and seek out details about where to vote in-person.”

“I can’t speak to any law other than SB 1,” Morris said, “but this does provide some evidence that the effect of being disenfranchised does make people even less likely to vote into the future.”

County officials observe the impact of new restrictions

Before the passage of SB 1, mail voters were not required to provide identification numbers, and although they still had to apply each year, election officials were allowed to send them reminders to resubmit their applications. The new law made such unsolicited reminders illegal.

In some counties, election officials said they’ve personally observed how the law’s requirements have affected voter participation and the way people vote.

Lisa Hayes, the elections administrator in Guadalupe County east of San Antonio, said that participation in mail voting rose in 2020, when the state allowed voters to hand-deliver their mail-in ballot during the early voting period because of the pandemic. During that year’s presidential election, Guadalupe County sent out more than 8,000 mail-in ballots to qualifying voters, and 90% were returned.

Since the new requirements passed in 2021, fewer people are voting by mail, Hayes said, and she’s seen voters become more frustrated.

For the November 2022 general election, the county sent out 3,354 mail-in ballots to voters. The return rate for that election was 81%. The return rate for the November 2024 presidential election went up slightly up to 84%, she said.

SB 1 included a provision that allows voters to correct errors on their application. Hayes said that in the period leading up to an election, her office is constantly answering calls from frustrated voters whose applications need to be corrected and resubmitted.

If the voter’s mail-voting application is missing one of the two required ID numbers, a signature, or the explanation of why they qualify to vote by mail, the elections office mails the voter a notice and a new application so they can correct it. Hayes said if voters correct one issue but fail to fix another, they must start the process over.

“Unfortunately, the voters have to jump through so many hoops to get into that corrective-action loop, that they just get frustrated and they give up,” Hayes said. In some cases, voters will send in two or three corrected applications before they get approved. Others opt to vote in person instead.

“These are the voters we’re supposed to be trying to help,” she said. “They need the help. They need to vote by mail. It’s not just a convenience for them, it’s a need. So of course they’re frustrated.”

Diana Leggett, 83, volunteers helping people who live at assisted-living facilities and nursing homes in Cooke and Grayson counties in North Texas. In 2022, she focused on helping seniors to navigate the new mail ballot rules.

“When you’re 90 years old, you’ve voted all your life, but you sure as heck don’t remember what you put down the first time you registered to vote,” Leggett said, referring to the requirement that ID numbers match what’s on file. “Some don’t have a driver’s license anymore or don’t know the number.”

When residents had their mail ballot applications rejected, she said, they often didn’t try again.

To keep voters from becoming frustrated, election officials have had to find ways to ensure voters are aware of the requirements to vote by mail.

Kaleb Breaux, election administrator for Collin County in North Texas, said his staff recalls the 2022 primary as a “rough mail ballot election.”

The county had over 7,000 mail-in ballots, and over 700 were rejected due to the new ID requirements, he said. To help voters, he said, his office began to insert instructions with the applications and the ballots “to help draw voters’ attention” to the sections with the new requirements. And it helped.

In the November general election, Breaux said, the county rejected just 85 ballots for ID requirement issues.

Natalia Contreras covers election administration and voting access for Votebeat in partnership with the Texas Tribune. She is based in Corpus Christi. Contact Natalia at ncontreras@votebeat.org.